FILE — Rent-stabilized apartment in New York, on Sept. 27, 2024. New York City could soon raise rents on some of its most affordable apartments to help landlords who say they aren’t earning enough. But renters say they’re hurting, too. (James Estrin/The New York Times)

- NYC rent-stabilized landlords report 12.1% increase in net operating income despite claims of financial distress.

- Older buildings in low-income neighborhoods show minimal NOI growth, raising concerns about property abandonment.

- Mayoral candidates split on rent freeze proposals as affordability becomes central campaign issue.

Share

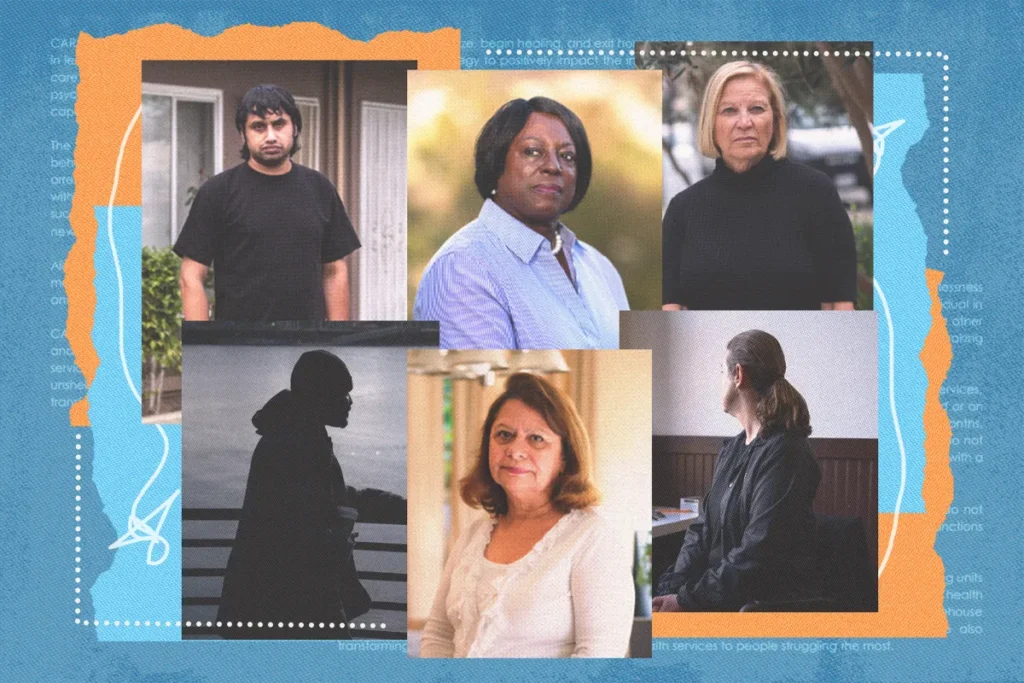

The landlords of New York City’s 1 million rent-stabilized apartments, an important source of affordable housing, often say they aren’t making enough money from rent to run their buildings. Some claim the situation is now so bad that it reminds them of the 1970s, when real estate values plummeted and owners abandoned thousands of buildings in low-income neighborhoods.

This is true, these landlords assert, even though a city panel has allowed them to increase their rents nearly 17% since 2014. The panel, the Rent Guidelines Board, is backing increases again this year, with a final vote expected later this month.

So why does a report released by the board in March suggest that these landlords are actually doing pretty well?

The report found that rent-stabilized landlords’ net operating income — revenue from rent, minus costs — was up 12.1%. The apparent contradiction has become a major talking point in the city’s mayoral race, in which affordability is a top issue and most of the Democratic candidates support a rent freeze. The decision of the panel, which is appointed by the mayor, can increase costs for some 2 million people.

So who’s right?

What Exactly Is Net Operating Income, and Why Does It Matter?

Net operating income, or NOI, takes into account the revenue a landlord gets from both residents and businesses in the building, minus costs that include maintenance, fuel, insurance and labor. It does not factor in income taxes or debt payments.

Still, the figure is one of the most important indicators of an apartment building’s financial health. Banks, investors and government officials often look at NOI to decide whether a landlord should receive loans or subsidies.

If landlords want a loan to pay for a new roof or heating system, for example, they need to show that the building’s NOI can cover the debt. The NOI also helps determine the building’s value, and, as a result, the amount of tax revenue the city might collect from the owner.

“It doesn’t have to be a ‘double your money in five years’ investment,'” said Michael Johnson, a spokesperson for the New York Apartment Association, a trade group representing rent-stabilized landlords. “It just has to be a safe investment.”

If NOI Is Up, Landlords Must Be Doing Well, Right?

It’s complicated.

While NOI is a key figure, it is not the full picture of a landlord’s financial situation. It does not reveal whether landlords have other income streams or investments, or how much money, if any, they owe on a building’s mortgage.

There’s also a time lag in the data. The 12.1% increase reflects the changes from 2022 to 2023, when the city was rebounding from the worst of the coronavirus pandemic.

The report’s NOI data covers a diverse universe of housing types, including any apartment building that has at least one rent-stabilized apartment. It would include, for example, a new building that has 80 market-rate units and 20 rent-stabilized units.

Johnson said the increase in NOI reflected changes in these mixed buildings. As the proportion of rent-stabilized units increases in a building, the NOI decreases, city data shows.

Doesn’t Any Increase Still Sound Pretty Good?

Rafael Cestero, the CEO of the Community Preservation Corp., a nonprofit that lends money to owners of older rent-stabilized buildings, said the broad 12% increase masked “really deep distress” in lower-income neighborhoods.

Cestero, a former city housing commissioner, said many owners were struggling to cover debt payments.

The nonprofit has roughly 600 loans out covering some 22,500 units. Cestero said that in 2023, the most recent year for which data was available, the NOI couldn’t cover the debt for some 28% of the loans, according to a survey of its portfolio. Cestero said that number was typically around 10%.

He said the worry was that these buildings would deteriorate, or ultimately be abandoned by landlords, as they were in the ’70s.

“We’re dangerously close to a situation where we have an unsustainable rent-regulated housing stock except for the buildings that are the nicest buildings owned by the institutional owners,” he said.

Because of the way the system was set up, about 80% of rent-stabilized units are in buildings that were built between 1947 and 1974. They are typically more affordable, with an average rent of $1,477, compared with $2,219 for those built later.

And in these older buildings, the NOI went up 3.1%.

By law, the Rent Guidelines Board must consider the “economic condition of the real estate industry” and the cost of living in deciding whether the rent in rent-stabilized apartments can increase each year. The board’s decisions, though, tend to reflect the political priorities of the mayor, who appoints the board’s members.

When NOI is dropping, and owners can’t cover their debts or pay their taxes, the panel may feel compelled to allow increases.

But advocates for tenants say that shouldn’t be renters’ responsibility.

“Tenants can barely afford the rent we’re already paying,” said Cea Weaver, the director of the New York State Tenant Bloc, a nonprofit advocacy group. She added, “We shouldn’t have to pay the price with our hard-earned rent money for landlords’ bad bets.”

The nonprofit is asking New Yorkers to vote for Zohran Mamdani and Brad Lander, left-leaning mayoral candidates who have said they would oppose rent increases. Former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who is being supported by donations from rent-stabilized landlords, and Whitney Tilson, a former hedge fund executive, would not commit to a rent freeze during a recent mayoral debate.

Samuel Stein, a housing policy analyst at the Community Service Society, a nonprofit that supports low-income New Yorkers, said that some landlords were struggling with costs. But he said there were other programs and tax breaks they should pursue, instead of rent increases.

“It’s extremely expensive to build new housing at lower rents,” he said. “When we lose these rents they’re gone forever. We support any program that’s going to help these become habitable, decent housing.”

—

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Mihir Zaveri/James Estrin

c. 2025 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

7-Eleven Inc Says CEO Jeo DePinto to Retire