AB Hernandez, center, flashes a sign as she shares the first-place spot on the podium with Jillene Wetteland, left, and Lelani Laruelle during a medal ceremony for the high jump at the California high school track-and-field championships in Clovis, Calif., Saturday, May 31, 2025. In a rules compromise, AB Hernandez shared first place in the high jump and triple jump in the California high school championship, and shared spots on the awards podium, too. (Adam Perez/The New York Times)

- AB Hernandez shared top podium spots in three events, making history amid political controversy over transgender athletes in girls' sports.

- Despite protests and political pressure, Hernandez was met with cheers and support during California's fiercely competitive state track meet.

- A last-minute rule change allowed tied placements, aiming to balance fairness and inclusion without excluding Hernandez from competition.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

CLOVIS, Calif. — The California athlete at the center of a searing political debate over transgender girls competing in girls’ sports went home a winner Saturday in what is arguably the most competitive state track and field meet in the nation.

AB Hernandez, a junior from Jurupa Valley High School in Riverside County, shared first place in the high jump and triple jump, and also shared second in the long jump. Her spot on the awards podium was a sign of how complicated her participation in the competition had become.

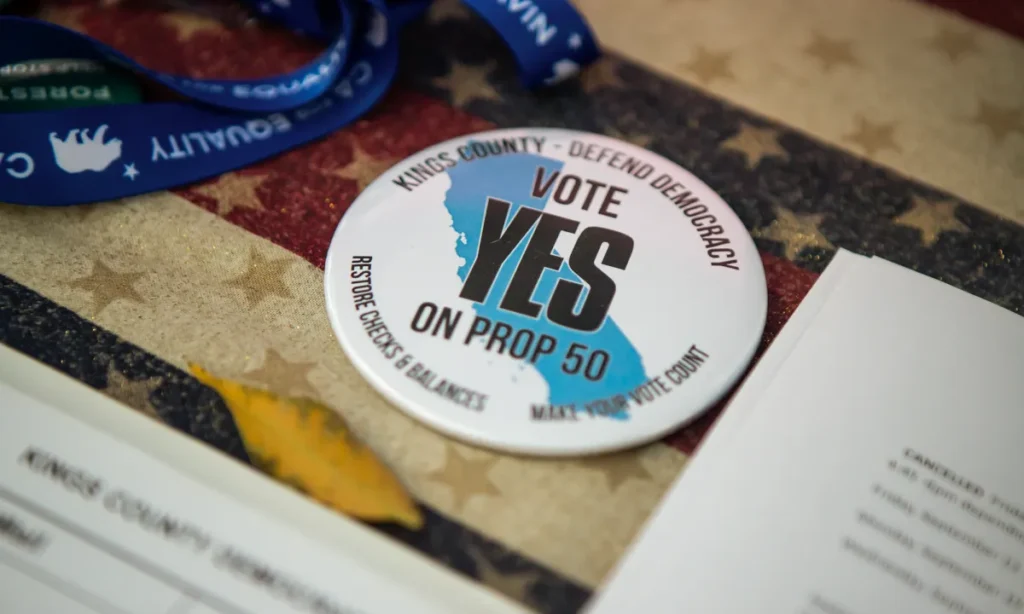

With President Donald Trump threatening to cut federal funding to the state if the trans girl competed, the event organizer changed the rules just days before the event in hopes of allaying concerns about the fairness of allowing Hernandez to compete. The athlete who finished behind Hernandez would be elevated to share her placement.

The first awards came after the long jump, and that moment of recognition did not turn out to be awkward or contentious, as some people had feared.

The two girls — Hernandez and Brooke White of River City High School — joked around like any teenage girls would, giving each other an enthusiastic double-handed high-five before they squeezed onto one step of the podium together. Then after both received medals, they put their arms around each other, held their medals out from their chests and smiled for photos.

Hernandez and the event’s winner — Loren Webster of Wilson High School — both had leaped more than a foot farther than anyone else in the event. For Webster, it was a back-to-back state title in the event before she heads off to compete at the University of Oregon.

For Hernandez, it was the celebration she had waited for after a week of enduring an intense spotlight. Two years ago, two trans girls had qualified for the state meet but withdrew because they were afraid for their safety. The online harassment had grown ominous.

In an emailed statement from the group TransFamily Support Services, which is representing Hernandez’s family, her mother, Nereyda Hernandez, wrote that her child has been attacked for “simply being who they are.”

She wrote that this is her daughter’s third year in sports and that competitors have always showed her respect and sportsmanship, but recently adults — “some even in positions of power, who should be protectors of our youth” — were the ones harassing her.

Hernandez’s performances drew interest far beyond the stadium in Clovis, a city near Fresno. Her participation, allowed under a 2013 state law that said students could compete in the category consistent with their gender identity, has fueled a searing political debate.

Gov. Gavin Newsom of California, a Democrat, earlier this year called it “deeply unfair” that trans girls compete in girls’ events.

On Saturday, hours before the meet, Steve Hilton, a Republican candidate for governor, also weighed in on the issue, holding a campaign stop just outside the stadium.

Flanked by activists holding up signs that read “Save Girls Sports” and joined by the mayor pro tem of Clovis, Diane Pearce, Hilton called out Newsom for not adequately addressing the issue of trans girls competing in girls’ sports.

“Every time he’s asked about that, he just says, ‘Oh, it’s too difficult and there’s nothing we can do,’” Hilton said, adding that there is, in fact, something that he could do: repeal the law that allows trans girls to play. He said he would press for that.

At the meet, some coaches inside the stadium acknowledged the complexity of the situation and were sympathetic to the trans athlete’s place in the middle of a national debate.

Martial Yapo, an assistant track coach at Santa Margarita High School, said the teenager has forced him to contemplate what he would do if he were to coach a trans athlete facing added scrutiny.

“I don’t have the answer, but I’m going through the same process as many other people,” Yapo said. “But being a decent human is more important.”

Bryn Williams, an assistant sprint coach at the school, which had athletes competing Saturday, said the new measures about final placement seemed reasonable given that the issue arose such a short time before the event.

“I think it is the definition of a compromise — trying to meet in the middle over something knowing that not everyone is going to be 100% happy with the decision that was made,” she said.

What put Hernandez at the center of the issue’s spotlight was that she was good at her sport. She had gone into the meet as one of the favorites in the long jump and triple jump, worrying some coaches and competitors that she would win those events and displace girls who would have won state titles if she had not competed.

The points she scored would matter, too, because schools were vying for a team title and the higher an athlete places, the more points she earns for her team. (Hernandez’s performance in three events ended up being enough to single-handedly vault her high school, Jurupa Valley, into fourth place out of 91 girls teams that scored points in the state meet.)

With those concerns looming, the California Interscholastic Federation, the entity that organizes the state meet, crafted the last-minute compromise to try to keep the competition fair without excluding athletes.

Once Saturday’s finals began, people outside the stadium chanted through bullhorns, “No boys in girls’ sports,” and some people high up in the stands shouted the same thing during Hernandez’s first event, the long jump. But before she took off down the runway, cheers drowned out the chanting, with several people shouting, “Go, girl!”

—

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Orlando Mayorquín and Juliet Macur/Adam Perez

c. 2025 The New York Times Company