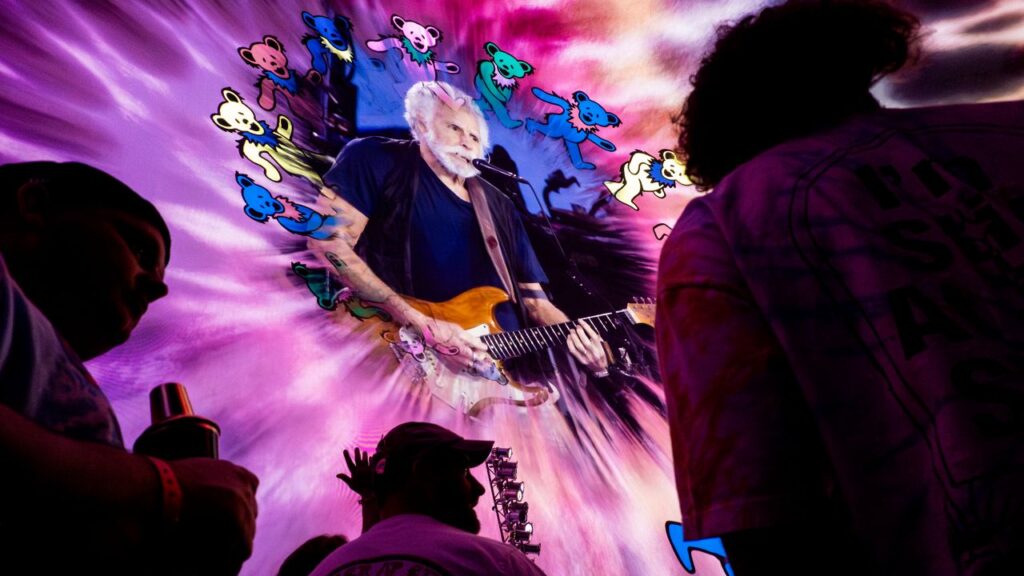

Former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and Gov. Gavin Newsom greet each other during a press conference in Antioch, Aug. 11, 2022. (CalMatters/Martin do Nascimento/File)

- Touting his new infrastructure czar back in 2022, Newsom framed the partnership as a way to save taxpayers money.

- Governor’s office declined to make anyone available to speak with CalMatters about the project and refused to answer questions.

- Villaraigosa was paid more than $380,000 by California Forward, whose donors included groups with an interest in state infrastructure projects.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

At the request of Gov. Gavin Newsom, a nonprofit paid former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa more than $380,000 to advise the governor for about 10 months on how to overhaul California’s approach to major infrastructure projects.

Touting his new infrastructure czar back in 2022, Newsom framed the partnership as a way to save taxpayers money. But California Forward, a nonprofit focused on economic development that was tasked with overseeing Villaraigosa’s work, could not cover the cost alone. As the project stretched on and initial costs more than doubled, California Forward turned to corporate donors to fill the gap — funders that have not been publicly disclosed until now.

Elected officials in California can solicit contributions, known as behested payments, to outside entities for a governmental or charitable purpose. Under state law, Newsom had to disclose that he asked California Forward to pay Villaraigosa.

But that disclosure requirement did not extend to California Forward, whose donors ultimately included organizations with an interest in state infrastructure projects. The nonprofit provided a list when CalMatters requested it, but the information was not otherwise available and is still not on any public disclosure forms.

Related Story: Gavin Newsom Finally Admits He’s Contemplating a Run for President

California Forward Raises $118K for the Job

California Forward said it raised $118,800 from a dozen donors to pay Villaraigosa’s salary and for events and travel for the project, including $30,000 from the Port of San Diego, $17,500 from SoCalGas, and $10,000 each from Doordash, Disney, Southern California Edison, AT&T, and the California Communications Association.

Many questions remain about why the Newsom administration took this approach, how the financial arrangement with Villaraigosa and California Forward came together, and if this approach upholds the spirit of disclosure rules for behested payments.

Sean McMorris of California Common Cause, a nonprofit that advocates for government in the public interest, compared California Forward’s role to a “clearinghouse” that allowed special interests to pay for the project without the usual disclosures that would have been required if Newsom had asked the organizations for the funding himself.

“It’s a loophole in the behested payment law,” McMorris said, “because it’s relevant information that the public and the press have a right to know.”

Newsom’s Office Won’t Answer Questions

The governor’s office, representatives from the nonprofit and Villaraigosa all praise the project as a win for California, which led the state to streamline construction of multibillion-dollar infrastructure projects.

But the governor’s office declined to make anyone available to speak with CalMatters about the project and refused to answer a list of questions, including:

- Where did the idea come from to hire Villaraigosa? The governor’s office refused to answer.

- Was anyone else considered for the role? The governor’s office refused to answer.

- Why did the governor feel that someone within the Newsom administration could not perform the same function? The governor’s office refused to answer.

- How did they settle on an outside funder to pay Villaraigosa? The governor’s office refused to answer.

Villaraigosa is now a candidate for governor pledging to “jumpstart” home, energy and transportation construction in California. His stint as infrastructure adviser is his most significant public service since he left the Los Angeles mayor’s office in 2013.

In an interview, Villaraigosa said he has no qualms about how much he earned for the position: $35,000 per month, plus expenses, to travel from the Oregon border to the Mexico border meeting with stakeholders and then produce a report with recommendations for speeding up infrastructure development.

Though he did not stop his other consulting work through the global firm Actum during that period, Villaraigosa said his role as infrastructure adviser was close to full-time and “pretty much took a front seat.”

By the time he stepped down 10 and a half months later, California had a glossy report and five new laws on the books, and Villaragoisa had earned $381,820 for his work. That’s more than California Forward paid its chief executive officer that year, tax filings show, and nearly $160,000 more than the governor’s own state salary.

“I think it was a huge return on investment for the state. And that’s what they offered,” Villaraigosa said. “I know I can say that California Forward and the governor’s office felt like I went above and beyond.”

How the Deal Came About

In the wake of the passage of the federal infrastructure bill in late 2021, the Newsom administration was looking to maximize California’s access to an expected $550 billion in newly authorized spending over the next few years.

So in August 2022, the governor brought on Villaraigosa to “design strategies to advance the State’s priorities and interests,” “serve as the key State liaison for local elected officials interested in federal infrastructure funding,” “provide input for and assist in development of messages” and “maintain regular contact” with federal policymakers, among other duties, according to a memo prepared that September by Newsom’s then-chief of staff Jim DeBoo.

It’s not entirely unusual for Newsom to turn to outside consultants for state government projects. In 2020, he notably convened a star-studded task force of business leaders, led by the former hedge fund manager and presidential candidate Tom Steyer, during the early days of the coronavirus pandemic to help guide his reopening strategy. The participants were not compensated.

But the Villaraigosa appointment raised eyebrows because Newsom was pulling a former political rival into his orbit. They had faced off during the 2018 gubernatorial primary, where Villaraigosa finished third, which Newsom alluded to during a joint press conference announcing his role.

“I remember running against this guy saying, the one thing I can’t run against is how effective he was on drawing down federal funding as mayor of Los Angeles,” Newsom said.

Villaraigosa was also notably not formally joining the Newsom administration or volunteering his time. Rather, he would be paid for his work, at the governor’s request, by California Forward.

Villaraigosa said he was approached about the infrastructure adviser position by DeBoo — who once served as chief legislative representative in his mayoral office — after the governor’s office had gone through a number of other people. Villaraigosa said he was told that all states had somebody to coordinate their relationship with the federal government on infrastructure and he had the best experience to guide California. DeBoo did not return multiple calls and emails requesting an interview.

Despite his contentious relationship with Newsom during the 2018 gubernatorial campaign, Villaraigosa immediately accepted the job.

“We both had a dream. We wanted to be governor. But it wasn’t personal,” Villaraigosa said. “We had a long relationship.”

He said he was not surprised to be asked, because of his past accomplishments on infrastructure projects in Los Angeles, which had even led him to be considered for transportation secretary in President Barack Obama’s second term.

Villaraigosa said the governor’s office offered to pay him and he agreed, without much negotiation over his fee. The compensation was always going to come from an outside group, he said, which Villaraigosa preferred, because being employed by the state would have involved too much bureaucracy.

“I didn’t want those complications,” he said. He did not elaborate further.

‘That’s Where the Ick Factor Sets In’

California Forward is best known for its annual economic summit bringing together California elected officials and civic leaders, which has featured Newsom as a speaker nearly every year since he became governor.

Villaraigosa led “stakeholder engagement” and gave “strategic advice” to the nonprofit as he worked on the infrastructure project, according to details from the financial records filed with the state.

Former California Forward CEO Micah Weinberg called the arrangement a “fantastic success,” with Villaraigosa’s recommendations leading to new laws to speed up the construction of green infrastructure in the state.

“In an era of people questioning government expenditures, this is just about one of the best deals that the government has ever gotten, because it didn’t cost the government and the California taxpayers anything at all,” Weinberg said.

California Forward’s fundraising and other revenue dropped by nearly two-thirds, to about $2.7 million, during the 2022-23 fiscal year, its federal income tax filing shows. Still, the nonprofit paid Villaraigosa more than Weinberg — who made $303,214 in that period — pulling from its reserves to cover most of the former mayor’s salary.

Both the governor’s office and California Forward said Newsom had no role in soliciting corporate donors for the project, meaning there was no legal obligation to report the fundraising to the state.

Taxpayers consequently had less insight into who was paying for a project with significant implications for the future of major public works in the state.

Weinberg defended the financial arrangement for creating a separation between California Forward’s fiscal sponsors and the final recommendations. He said Villaraigosa did not know which donors were funding the project and there was no quid pro quo.

“It was an initiative that was paid for by a nonprofit organization that has hundreds of supporters, which I think is a better way of doing this,” he said.

But McMorris, the transparency, ethics, and accountability program manager for California Common Cause, argues that this is an “ethically suspect” way of using behested payments, because it buries the true sources of funding.

“It looks better politically if an innocuous nonprofit is giving the money,” he said, even though it’s really special interest groups that are paying. “They don’t even have to report that they’re giving money to the third party. That’s where the ick factor sets in.”

McMorris said it’s important for the government to use taxpayer money for its priorities, because it holds elected officials accountable to do things that they believe are defensible to their voters.

“This is what taxpayer money is for,” he said. “I don’t understand this idea that we’re just going to outsource government to the private sector, because now you introduce all this conflict of interest and the possibility for conflict of interest, which then results in the end result potentially being tainted.”

‘He Helped Set the Tone for the Conversations’

During his year as Newsom’s infrastructure adviser, Villaraigosa participated in more than 180 meetings, tours, roundtables, events, calls, and Zooms for the infrastructure report, his spokesperson said. That included a trip to Washington, D.C. in September 2023, after he was no longer being paid for his work, to meet with congressional leaders such as then-House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and California’s Democratic delegation about infrastructure funding.

Villaraigosa consulted with former advisers from Los Angeles, who volunteered their insights for the project, and got the Boston Consulting Group to help write the final report pro bono.

But he was primarily assisted by California Forward staffers, including Ismael Herrera, who joined Villaraigosa on a statewide listening tour throughout the final months of 2022, coordinating with the governor’s office about who to invite to the sessions and taking notes. Herrera said the project consumed about half his work time during that period, traveling to rural communities with Villaraigosa, then sitting for hourslong listening sessions, plus making site visits and doing prep work.

Those conversations — which also focused on the impacts of infrastructure projects for the workforce and the environment — involved public transportation agencies, local and regional government officials, water districts, universities and community colleges, community organizations and nonprofits, faith-based and environmental justice groups, labor unions and more, Herrera said.

“I thought (Villaraigosa’s) involvement was very valuable and he put a lot of time and effort into this,” Herrera said. “He helped set the tone for the conversations, and also did a lot of listening, a lot answering questions that people had.”

The governor’s office said the listening sessions were not considered open meetings subject to California’s public records laws.

The recommendations ultimately informed a package of bills, introduced by Newsom in May 2023, aimed at speeding up construction of big infrastructure projects by streamlining the state approval process. After facing pushback from environmental groups, a version of the package passed the Legislature about a month later.

“I was given great latitude,” Villaraigosa said. “Obviously these were recommendations. I was doing this on behalf of the governor. But the governor and his staff made almost no changes to our proposals.”

The governor’s office cited Senate Bill 149 — which sets a 270-day limit for wrapping up environmental lawsuits for water, energy, transportation and semiconductor projects that are certified by the governor — as the most significant change.

Since then, four projects have received certification for this expedited review, including Sites Reservoir, a controversial plan to build the state’s first new reservoir in more than 50 years in Colusa County.

This article was originally published on CalMatters and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.