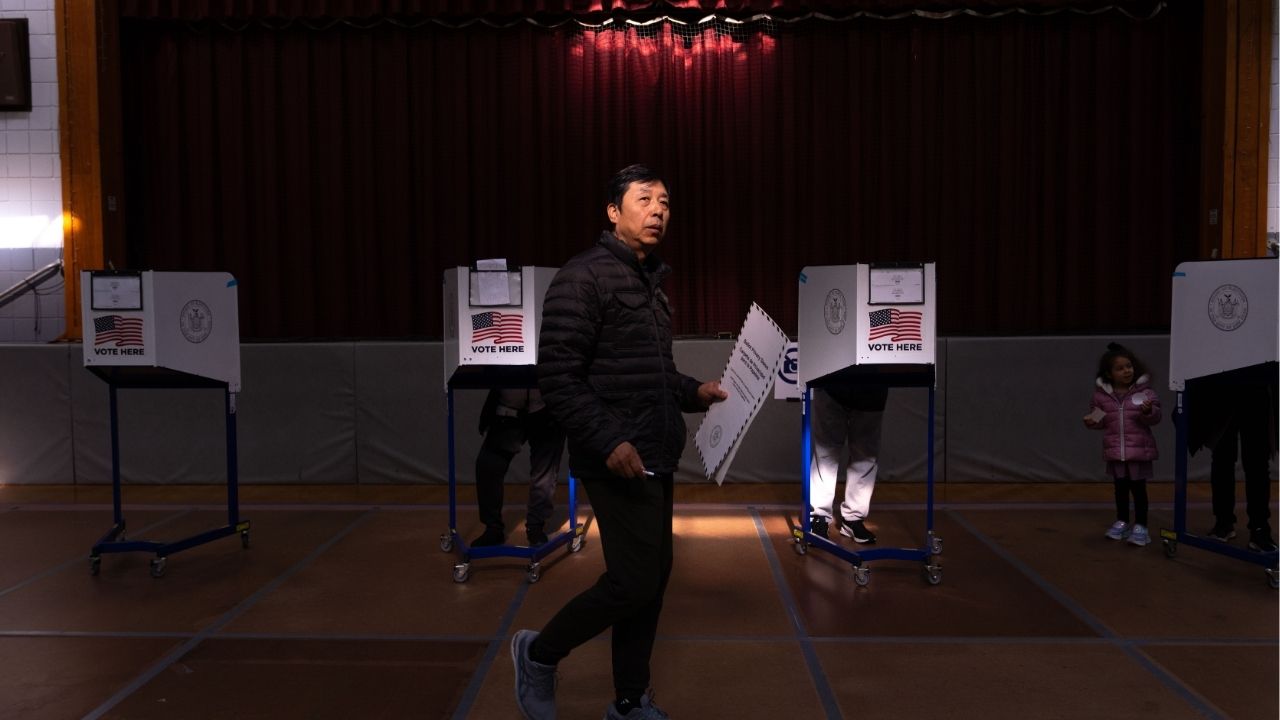

An early voter at a polling place set up in a church on Staten Island, where a Republican congresswoman represents the 11th Congressional District, on Sunday, Oct. 26, 2025. A suit filed by an election law firm contends that the state’s 11th Congressional District is drawn in a way that disenfranchises Black and Latino voters. (Adam Gray/The New York Times)

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A lawsuit filed Monday on behalf of four New Yorkers charges that the state’s congressional map unconstitutionally dilutes Black and Latino votes in a district that covers Staten Island and part of southern Brooklyn, according to a copy of the lawsuit obtained by The New York Times.

The case marked New York’s official entrance into the national gerrymandering arms race. Rewriting the state’s existing congressional districts represents one of Democrats’ best hopes of improving their chances in the 2026 midterm elections.

Filed in state Supreme Court in Manhattan, the lawsuit argues that the lines for the 11th Congressional District unfairly disenfranchise Black and Latino residents under the state’s newly passed Voting Rights Act. The district is represented by Rep. Nicole Malliotakis, the only Republican member of Congress in New York City.

The combined Black and Latino population on Staten Island has grown from 11% to 30% over the past 40 years, the suit notes, arguing that the current boundaries “confine Staten Island’s growing Black and Latino communities in a district where they are routinely and systematically unable to influence elections.”

A representative for Malliotakis did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

This lawsuit was filed by Elias Law Group, a Washington, D.C.-based firm that has handled much of the party’s redistricting litigation.

Filing a lawsuit is a far less certain path to redistricting than having a partisan legislature simply draw new maps and pass them into law, which is what Texas did earlier this year. But New York placed its redistricting process in the hands of an independent commission years ago, in hopes of insulating it from partisan politics.

Redrawing Boundaries

Redrawing legislative boundaries for Congress and state legislatures is typically done at the start of the decade following the census. But the Trump administration has upended that cycle, pushing Republican-controlled states to redraw their congressional maps before the 2026 midterms in an effort to ensure the party maintains control of the House of Representatives.

Republicans have already redrawn maps in Texas, Missouri and North Carolina, netting their party as many as seven likely pickups before any votes have been cast.

Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York, the official head of the state Democratic Party, pledged to “fight fire with fire,” saying: “If they’re going to rig the system, I refuse to sit on the sidelines and let our democracy further erode any more than it already has under the Trump administration.”

But Democrats may face an uphill battle convincing a judge that the current lines are unacceptable: It was just last year that they drew and approved the map, which Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, the House minority leader, himself blessed as a modest but meaningful improvement over the previous lines.

Democrats in Albany devised the current lines for New York’s 26 congressional districts after the state’s redistricting commission failed to come to a consensus and an unsuccessful attempt by the party to gerrymander to its advantage.

In addition to the states where maps have already been redrawn, the White House had mounted an aggressive push in Indiana to force the legislature to eliminate the state’s two Democratic districts, with the president himself calling legislators earlier this month to persuade them to draw new maps.

On Monday, Gov. Mike Braun, a Republican, called a special legislative session to redraw congressional maps in his state. But immediately after his announcement, a spokesperson for the state’s Senate Republican leadership said that “the votes still aren’t there for redistricting,” adding to the uncertainty surrounding the effort.

Kansas, Nebraska Leaders Open

Republican leaders in both Kansas and Nebraska have indicated that they are open to redrawing before the midterms, though neither have yet taken formal steps to do so. And Florida Republicans are contemplating new maps as well.

Until this month, the only Democratic countermove before the midterms was in California, where Gov. Gavin Newsom proposed a temporary suspension of the state’s independent redistricting commission in order to draw five new Democratic seats. That effort will need to be approved by voters in November in order to move forward.

But last week, Virginia Democrats made the surprise announcement that they would also embark on an effort to redraw their maps should Democrats hold both chambers of the legislature this November, possibly netting two or three more seats for Democrats. The legislature was expected to meet Monday to begin the process.

Democrats are hamstrung by the fact that many Democratic-controlled states have passed redistricting reforms in recent years, with the legislatures yielding the power to draw legislative maps to independent commissions, in an attempt to remove politics from the process.

The few Democratic-controlled states where legislatures still draw maps — such as Illinois and Maryland — have already drawn aggressive Democratic gerrymanders that make it difficult to extract more seats.

This has left the courts as one of the last remaining avenues for a state like New York, which passed a law establishing the bipartisan commission to redraw its maps in 2014.

—

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Grace Ashford and Nick Corasaniti/Adam Gray

c. 2025 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Philippine Mayor Survives Rocket Attack, TMZ Reports

Fresno Drivers Face Highway 180 on-Ramp Closure Wednesday