Fairgoers walks around the Kern County Fair in Bakersfield on Sept. 26, 2025. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

- California’s Prop. 50 election pits Democrats’ redistricting push against rural conservatives fearing gerrymandered maps will weaken their voices.

- Newsom’s plan redraws districts to counter GOP gains in Texas, sparking backlash from farmers worried about lost representation.

- Prop. 50’s outcome may hinge on turnout, with both parties racing to mobilize uninformed voters through personal outreach.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

Along the highways of California’s San Joaquin Valley, as field workers harvest almonds and pistachios and tractors churn dusty top soil into the already hazy air, drivers can’t miss the giant yellow billboards.

“VOTE NO on PROP 50. STOP Newsom’s Rigged Elections!”

Maya C. Miller

CalMatters

The signs in English and Spanish, paid for by Republican Assemblymember David Tangipa of Fresno, are one of the only clues in this region that California voters are hurtling toward a statewide special election next month.

Residents here would be the first to tell you they spend far more time thinking and worrying about the rising cost of living, access to water for their farms, homelessness and the threat of immigration raids than the shape of California’s 52 congressional districts.

Many of them don’t realize that in just a few weeks, they’ll be asked whether they want to temporarily change their districts — and for some, their representation in Congress — in a gerrymander that favors Democrats. And unlike in politically attuned coastal hubs like the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles, traditional online, TV and mail campaign ads are rarely enough to get people to vote. Often they need an in-person push from a friend or family member.

But even those unfamiliar with the term “Proposition 50” proved they could quickly form an opinion as soon as someone — a friend, a relative, a journalist, a politician — explained the measure.

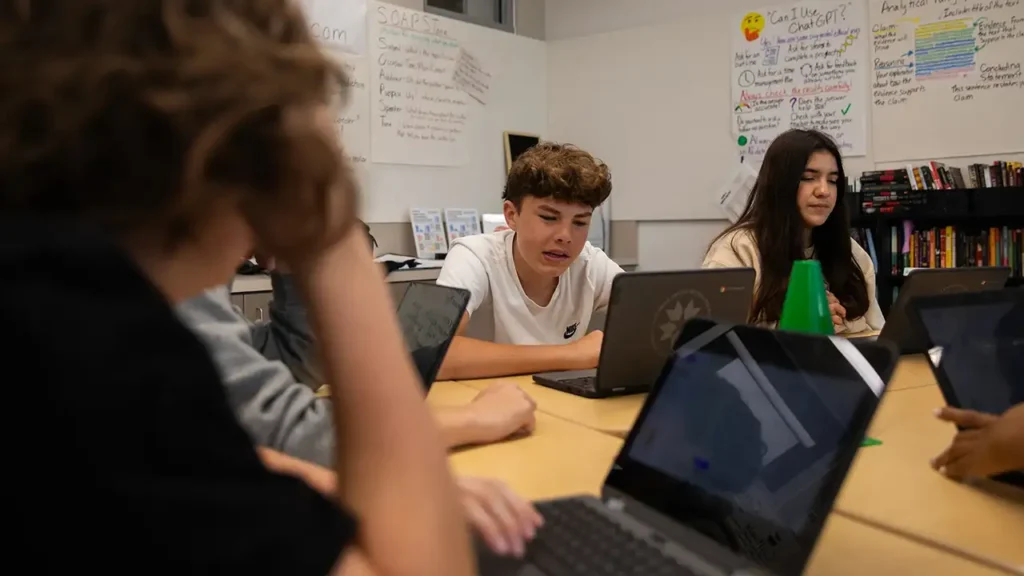

At the Kern County Fair in Bakersfield, past the Ferris wheel and rows of food stalls hawking corn dogs and Labubu-themed drinks, congressional candidate and educator Randy Villegas shook hands and snapped selfies in the exhibit hall with fairgoers at Democrats’ pamphlet-laden table.

Nearby waited Villegas’s former drumline student Nickolas Orozco, 29, a cafeteria and playground security monitor for a local elementary school. Although he was raised in a Democratic household, Orozco adopted more conservative views post-graduation when he moved to North Carolina. Now, back in Bakersfield, he considers himself a “true neutral” politically. He has supported both Democrats and Republicans in the past, and his top concerns are affordable housing and resources for K-12 schools.

Orozco’s stern expression melted into a grin as his former teacher greeted him with a hearty handshake and slap on the back. He told Villegas he knew “little to nothing” about the upcoming special election and was at the Democrats’ booth to learn more.

“Educate me, like you used to,” Orozco said.

As Villegas explained how congressional districts are drawn every 10 years after the Census to ensure proportional representation, Orozco interjected.

“I think I may have lied, I heard about this,” he said excitedly. “This is happening in Texas.”

Yes, Villegas said, Texas Republicans redrew their maps this summer, in the middle of the decade, to help their party keep control of the U.S. House. In response, California is asking voters to temporarily suspend its current maps, drawn by an independent citizens commission, and instead adopt gerrymandered districts that favor Democrats for the next five years. Ballots are already going to voters.

“Can I count on you to vote ‘Yes’ on it?” Villegas ultimately asked.

“I don’t see why not,” Orozco replied. “I mean, we’ve got to stand up to Texas!”

A District Democrats Have Eyed for a Long Time

Newsom and his party hope Prop. 50’s new maps will help their challengers oust five congressional Republicans and offset likely GOP pickups from mid-decade gerrymandering in Texas and Missouri. But a pickup in the 22nd Congressional District, which currently spans from the town of Hanford through the San Joaquin Valley to Bakersfield, is far from guaranteed.

Democrats have long dreamt of ousting Republican Rep. David Valadao, a dairy farmer who fashions himself a political moderate. Yet to their disappointment, Valadao has consistently defied political gravity and Democrats’ voter registration advantage in the district. His only loss in the last 15 years came in 2018 during the first Donald Trump presidency after Valadao alienated voters on both sides of the aisle by voting to repeal the Affordable Care Act and in favor of Trump’s first impeachment.

But two years later, Valadao won his seat back even as former President Joe Biden won the same district by more than 10 percentage points over incumbent Trump.

A campaign spokesperson for Valadao, Andrew Renteria, did not respond to multiple emailed requests for an interview.

Assemblymember Jasmeet Bains, a Bakersfield doctor who specializes in addiction treatment, hopes she can lead Democrats to a repeat of 2018 by punishing Valadao for his vote to pass Trump’s megabill.

The legislation could in the next 10 years push an estimated 57,000 of Valadao’s most vulnerable constituents off Medi-Cal, the state’s health care program for the poor, according to an estimate from Democrats on the congressional Joint Economic Committee. Another 8,200 would lose access to health care coverage through the Affordable Care Act. Valadao’s district has the highest Medicaid enrollment rate of any congressional seat, according to an analysis by The New York Times of data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a liberal think tank.

Yet Bains, who has often been a thorn in the Democratic Party’s side for her moderate approach in the state Legislature, has distanced herself from Prop. 50. She was the sole legislator to buck her party and vote against the plan to fast-track the special election. Bains declined to be interviewed through her spokesperson, Adam Capper, who said she had no additional comment on Prop. 50.

“I oppose any effort to circumvent independent redistricting, and the courts should act to stop these political games,” Bains said previously. “We don’t need more ways for politicians to rig the system.”

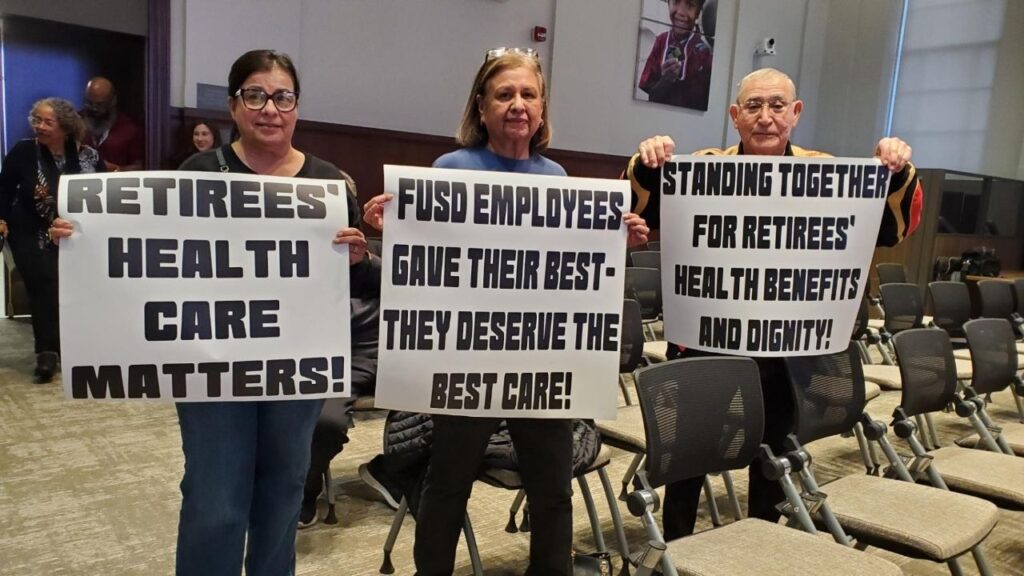

Farmers and other rural Californians are spooked that the new maps will dilute their votes by drawing them into districts with voters from urban centers. For instance, a new proposed district in Northern California lumps conservative, rural Modoc County with some of the state’s wealthiest communities in uber-liberal Marin County.

In the San Joaquin Valley, Prop. 50 would stretch the compact 22nd Congressional District, which currently includes parts of Kings, Tulare and Kern counties, to include the northwest corner of the city of Fresno and smaller towns like Kerman.

Jenny Holterman, a fourth-generation farmer in Kern County whose family primarily grows almonds, denounced Democrats’ redistricting plan as a “power grab” that threatens to leave farmers and rural Californians with far fewer voices in Congress.

“This is not a game. This is our livelihood. This is our representation that you’re playing with,” said Holterman. She called the Democratic effort to oust him “really sad.”

“He is that boots-on-the-ground that actually understands how an agriculture business works,” Holterman said. “That’s who should represent the valley.”

Voter Turnout Could Decide Prop. 50’s Fate

Campaign strategists and election watchers agree there are two big questions whose outcomes could decide the race — who can sell a simpler message, and which side can convince more uninformed voters to turn out.

Republicans could benefit from energizing conservatives as well as uninformed voters who, with limited information about a complex subject, might be predisposed to vote “no” and keep the status quo.

“If the message is simple enough — ‘Hey, stop Trump,’ or ‘Hey, protect our elections,’ — it’s likelier that they’ll end up turning out more voters in the valley,” said Blake Zante, executive director of nonprofit The Maddy Institute which focuses on public policy affecting the San Joaquin Valley.

On a recent Friday just after 7:30 a.m., Democrats Doug Hillhouse and John Waddell waved American flags and signs from an overpass on Highway 198, just outside the town of Lemoore.

Dubbed the “Bridge Brigade,” the two men, along with several others from the Kings County Democrats, alerted the drivers below to the upcoming special election and urged them to vote “Yes.” Lashed to the bridge was a series of poster boards that read, “Worried? Register to vote. Yes on 50,” while another urged drivers to honk their horns.

“We’re out here fighting the demagoguery,” said Hillhouse, a former Republican who became a Democrat after Trump took over the GOP. He argued that Prop. 50 represents a proportional “tit for tat” response to Texas Republicans.

“If we don’t get that passed, we’re going to be doomed to Republican rule,” said Waddell, who stood next to Hillhouse on the bridge and carried a sign that read, “ICE is gestapo.”

While the bridge brigades, billboards and television advertisements might raise awareness about Prop. 50, those alone won’t guarantee that voters turn out, said Zante. Instead, person-to-person voter engagement through door-knocking — but especially through conversations with friends and family — is much more effective at getting voters to cast ballots.

Reno Lanfranco, who owns several businesses in Kerman, about 20 minutes west of Fresno, views Prop. 50 as Newsom’s personal vanity project and a waste of taxpayer money. He blames California Democrats for high taxes — sales, income and gasoline — as well as what he feels is a byzantine regulatory system.

“I’m telling everybody — all my employees, if they want to listen to me or not, and all my customers — vote no on it,” said Lanfranco, an imposing figure with his plaid work shirt stretched taut across his muscled frame, as he surveyed his hardware store.

Prop. 50 would also disenfranchise conservative voters like himself, he argues, which is especially infuriating since Democrats hold a legislative supermajority and control all statewide offices.

“We have very few Republicans in office now and it’ll just squeeze the rest of them out,” he said. “That’s not right.”

One of Lanfranco’s employees credits his boss with helping him understand what’s at stake in the next special election. Shawn Delgado, a 24-year-old clerk at the hardware store, hadn’t heard of Prop. 50 until a CalMatters reporter asked for his opinion on it. After some follow-up research and talking with his boss, he’s leaning toward a “no” vote.

“We already have a bipartisan committee to decide those maps,” said Delgado, who voted for the first time in 2024 and supported Trump. While he acknowledged that redrawing California’s maps might be “more fair as a whole for the country,” he argued California shouldn’t gerrymander and disenfranchise its own Republican voters just because other states are redrawing their maps.

Fear of Immigration Raids Could Keep Some Voters Home

One potential roadblock to voter education in the Valley is the palpable fear of immigration enforcement raids, even among citizens. The Supreme Court’s recent decision to allow law enforcement to racially profile their targets has stoked existing fears and prompted many Latino people to stay home, lock their doors and refuse to answer the door for anyone they don’t know, even if they are U.S. citizens.

Maria Pacheco, the mayor of Kerman and a frequent leader of local protests against immigration and customs enforcement, said many Hispanic residents are “politically disillusioned” and aren’t paying close attention to Prop. 50 — and she doesn’t blame them.

“How do you get the community to come out and vote when they’re afraid to come and go to the grocery store?” Pacheco said.

She noted that any white vans or SUVs that drive through town immediately trigger her and others who are fearful of ICE. “How do you get the community to want to participate when they’re seeing that their government is against them right now?”

But Pacheco also said she was enraged by the “racist and inhumane” rhetoric that Texas Republicans, specifically Gov. Greg Abbott, have used to justify their detention and deportation of Hispanic people who they claim are violent criminals or entered the country illegally. While ICE has not conducted raids in Kerman or the surrounding area, she’s on edge. It’s not a matter of if, but when, the immigration crackdown will come.

“Harvest is coming to a close. So, is this when they’re gonna do it? When we’re no longer needed?” she said.

After Texas redrew its congressional maps to give Republicans an edge in five additional districts, Pacheco was proud of Newsom and California for “not just sitting back and allowing it,” but taking a stand and asking the people to weigh in as well. She’s worked to turn that pride into momentum and is encouraging community members to participate in the special election.

In one-on-one and small-group meetings with Hispanic voters, Pacheco emphasizes that voting “Yes” on Prop. 50 with a mail-in ballot from the relative safety of their homes is a small yet crucial act of resistance and a step toward reclaiming the humanity the Trump administration and GOP states have worked to strip away.

“We can’t just sit and be complacent. We have to be brave,” Pacheco said. “We have to be uncomfortable for just a little while so that we can turn this around and make a difference.”

—

This article was originally published on CalMatters and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.