Share

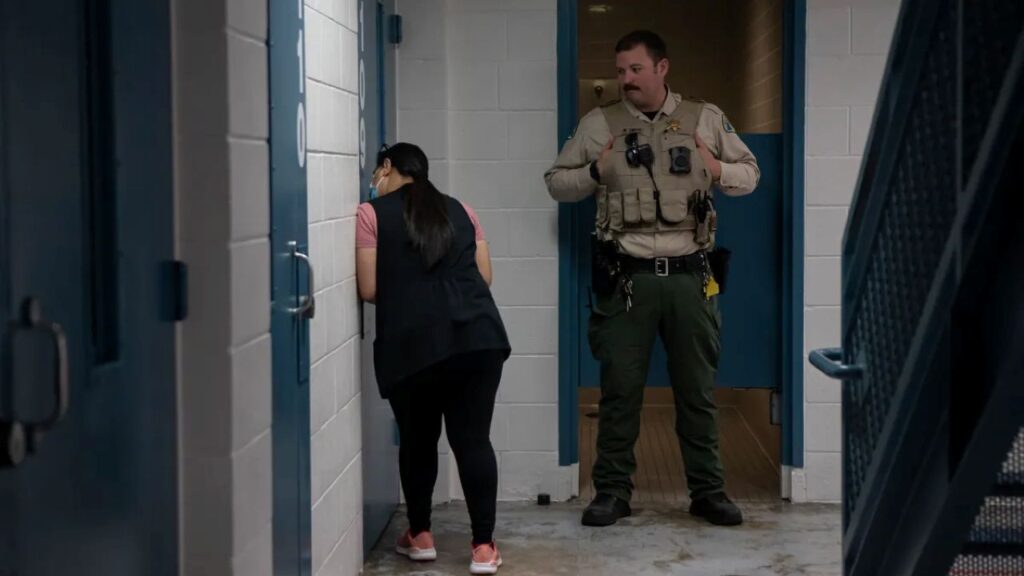

For decades, California teens who committed the most serious crimes – robbery, assault, murder – were sent to state juvenile prisons to serve their sentences.

Now that is about to change.

Elizabeth Aguilera

CalMatters

A controversial new law that takes effect next year will dismantle the state’s current juvenile justice system and transfer responsibility for convicted youth back to counties.

Orchestrated this year by Gov. Gavin Newsom in a swift move, the state’s Division of Juvenile Justice will no longer accept newly convicted young people after July 2021 – leaving counties with less than a year to plan for where to house the state’s most serious young offenders.

Opponents say they were stunned by the speed of the decision, and how little input was solicited from counties, probation officials, youth advocates and others affected by the dramatic overhaul.

“We were caught off guard when the administration put this policy into the works,” said Karen Pank, executive director of the Probation Chiefs of California. “This is the first time I’ve seen something so big get through like it did, so quickly.”

Even some advocates of the plan agree it was passed quickly, is not fleshed out, and could result in more youth being sent to adult prisons because counties are not prepared.

But the plan – while not perfect – will keep youth close to home where they might benefit from family and community support, proponents contend.

“If you are taken from SoCal and moved to Stockton, that impacts your ability to maintain those relationships, and it is a big deal for young people who are still going through phases of development,” said Chet Hewitt, president and CEO of Sierra Health Foundation. “Oversight of the local programs is going to be important now. There should be no difference whether you are in San Francisco or Fresno county.”

A spokesperson for the Division of Juvenile Justice declined to be interviewed.

A Turbulent Past

By the time Newsom signed this into law on Sept. 30, the state’s Division of Juvenile Justice was already in upheaval. Last year, Newsom decided to move the division from the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to the Health and Human Services Agency.

Then, along came the pandemic and the state budget was thrown into free fall. With dwindling revenues, Newsom included the system’s closure in his May budget revise, which focused on budget cuts and eliminated or significantly trimmed nearly all the expansive ideas he had proposed in January.

For now, the Division of Juvenile Justice will stay under Corrections until it completely shuts down.

It’s still unclear how much the state will actually save by closing the division because it has promised to reimburse counties for keeping the youth in custody, and to support their housing and rehabilitation needs.

The overhaul, however quickly it came, has been batted around for years as critics pushed for reform. Formerly known as the California Youth Authority, the division has a long history of controversy. In the 1990s, the agency was in the hot seat for reports of excessive punishment, abuse and violence. Lawsuits against the state brought change in how youth were treated.

At its peak in 1996, the system housed 10,000 inmates and operated 11 facilities from Los Angeles to Stockton to Ione in Amador County.

In the years since, the division has been shrinking because youth crime decreased and the state began limiting use of state facilities to only those who had committed the most serious crimes.

Today, the division houses 750 youths at three facilities – two in Stockton and one in Ventura County. The fire camp for young offenders in Pine Grove will remain open.

The new plan will not change life for those currently serving their time. They will stay in state lock-up until their sentences are over, or they transfer out at 25. Only when the last youth is out of custody will the division actually close entirely.

Youth who would have been sent to state custody after July 2021 will ideally be housed in their home county and provided support and rehabilitative services, according to the new law. In cases where counties cannot do this, the law allows them to contract with nearby counties, although no details have been worked out.

A Big Hand-Off to Counties

Under the new law, counties must create their own plans for how to deal with this population. The state is retaining some oversight with creation of an Office of Youth and Community Restoration and an ombudsman position to oversee the grants that will go to counties.

Some youth advocates say they are concerned about the differences that will emerge as 58 different counties, varying in size and resources, create their own approaches.

“There will have to be some centralization of counties – because some youth will need some services that are not available in every county,” said Mike Males, senior research fellow at the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice in San Francisco.

Some larger counties may be able to absorb the young offenders more readily with programs already in place. For example, Los Angeles County has the largest juvenile justice system in the country. By contrast, Alpine County, population 1,100, does not have a juvenile hall— or an adult jail, for that matter. Instead, it contracts with nearby El Dorado County for both services.

“I’ve been here for three years and thankfully we haven’t had a serious youth offender,” said Tami DiSalvo, Chief Probation Officer for Alpine County. “My first call would probably be to El Dorado.”

Some counties are also skeptical, given the vagueness of the state’s funding formula. Money will not be granted in a flat amount per youth but will instead be based on various factors, such as how much the country has relied on state facilities previously for youth incarceration.

The final plan has serious shortcomings that “do not set counties and youth up for success,” said Darby Kernan, deputy executive director of legislative affairs for the California State Association of Counties, in a statement.

The association, along with Urban Counties of California, Rural Counties Representatives of California and the County Behavioral Health Directors Association of California, have opposed the plan.

In a letter to the Legislature, the groups said the new system is “unworkable” and that the state “is attempting to reduce costs and transfer liability.”

Democratic Assemblyman Jim Cooper of Elk Grove, a former sheriff’s deputy, also opposes the plan, saying the state is dismantling a system that has created valuable programs— especially for young sex offenders.

“It took them a long time to get there and develop it,” he said. “Counties don’t have it and I don’t think they can replicate it the way (the Division of Juvenile Justice) has done it.”

Former Inmates, Differing Views

California youth advocates Frankie Guzman and Chet Hewitt have been there. Guzman spent years in California’s juvenile justice system in the 1990s for armed robbery. Hewitt served time decades ago as a teenager in New York’s Rikers Island for gang activity.

But they see this issue differently.

Guzman was arrested at 15 and spent six years in and out of state facilities. When he was intermittently free, he attended community college, which he says helped him find a better path.

He acknowledges the division has a terrible track record with violence, abuse and neglect, but he said that has improved since his time there. Guzman worries that without a state juvenile prison system, young people who commit the most serious crimes will get sent to adult prisons if counties aren’t prepared to help them.

“There is nothing in the plan to mitigate transfer to the adult system,” said Guzman, now an attorney and director of the California Youth Justice Initiative at the National Center for Youth Law.

Guzman said the state has dramatically decreased the number of youth being tried as adults but now worries that trend could be reversed if there is no alternative between county juvenile hall and adult prison. In 2008, 1,201 youth were tried as adults compared with only 66 in 2019, according to the W. Haywood Burns Institute, which analyzed California Department of Justice data.

Hewitt was 16 when he was convicted, spending seven months behind bars. He graduated from high school in Rikers Island.

“There was not a single redemptive or rehabilitative component in any of it,” he said. “All you could do is come out more harmed than you went in.”

His community, he said, is where he found redemption.

“They didn’t view me for what I did, they viewed me for what I could be,” he said. The state system “was not producing the kind of outcome we hope for kids.”

Hewitt went on to become president and CEO of Sierra Health Foundation. He supports the system’s return to local counties, so youth can be near family and community, he said.

But Will it Save Money?

But even Hewitt said he sees the potential pitfalls of having each county devise its own plan.

Meanwhile, the funding is murky.

According to the bill and the legislative analysis, the state estimates it will spend nearly $39.9 million in the first year and, by 2024-25, the state will funnel $208 million annually to counties. In addition, a one-time $9.6 million general fund distribution will be used to create the new office and help counties develop local plans.

The Division of Juvenile Justice is currently operating on a $220 million budget, which includes health care and education, according to the state.

This is what worries counties: They don’t know how much money they will receive per youth.

Males, the research fellow who supports the change, said counties fear losing what has been a good deal and now have to assume responsibility for these offenders.

The jury is out on whether counties can do better, Males said.

“This is an experiment,” he said. “Some will and some won’t.”

About the Author

Elizabeth Aguilera is an award-winning multimedia journalist who covers health and social services for CalMatters. She joined CalMatters in 2016 from Southern California Public Radio/KPCC 89.3 where she produced stories about community health.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Mountain Lion Trio Caught on Camera in Shaver Lake