Share

The Fresno City Council has considered paying for the defense of council president Nelson Esparza, who faces criminal charges of attempted extortion.

The details remain shrouded, but discussions over whether to use public funds for Esparza’s defense have been included on two recent closed session agendas. Esparza recused himself both times, according to the meeting minutes.

State law gives the city the right to pay criminal defense costs for an elected official, although it is not a requirement.

Sources told GV Wire that items on the council’s June 23 and July 21 meeting agendas focused on paying Esparza’s legal fees. The sources could not speak on the record because the conversations took place in closed sessions.

The Fresno County District Attorney’s office alleges Esparza threatened then-city attorney Douglas Sloan’s job in April, telling him to only perform work for certain members of the city council.

Sloan announced he was leaving his position soon after and is now city attorney in Santa Monica.

Esparza faces one felony count of attempted extortion and a misdemeanor count of violating the City Charter. His arraignment is set for Sept. 20.

If convicted, the maximum penalty is three years in jail. Esparza has denied the allegations and — in his only verbal public statements on the matter — said he plans to remain on the council and continue serving as president.

Esparza, through a campaign spokesperson, declined to comment for this story.

Some Councilmembers Want Public Discussion

Some councilmembers said discussions about paying for Esparza’s criminal defense should be held publicly.

“Would I support a public discussion if that was legally permissible? I certainly would. I support most things being out in public,” Councilman Garry Bredefeld said.

Councilman Mike Karbassi also supports an open discussion.

“I would also support a standing policy that taxpayer money never be spent on the criminal defense of an elected official,” Karbassi texted.

Councilman Tyler Maxwell declined to answer. Other councilmembers — Miguel Arias, Esmeralda Soria, Luis Chavez and Esparza — did not respond to requests for comment.

Discussion During Closed Session

Multiple sources speaking on background say the first closed session discussion revolved around Esparza’s pending defamation lawsuit against fellow councilmember Garry Bredefeld. State law allows leeway to cover such litigation. The second discussion focused on Esparza’s criminal charges.

Recollections of the June 23 meeting vary. Sources differ on whether an actual vote was taken about covering the costs of Esparza’s defamation lawsuit. If any vote was taken, nothing was reported publicly — a possible violation of the state’s open meeting law.

One source said the city council voted 5-0 in two votes to pay for both sides of the civil suit. Another said it was just a briefing on the situation; and the city attorney and/or city manager made an administrative decision to fund either Bredefeld’s defense, Esparza’s lawsuit or both.

Could a decision to defend a lawsuit be made unilaterally by the city’s administration? GV Wire asked Scott Emblidge, an attorney with San Francisco-based Moscone Emblidge & Rubens LLP and an expert on municipal law.

“That depends on the City’s charter or administrative code in terms of who is authorized to make that type of decision. In San Francisco, for example, the City Attorney does not seek Board of Supervisors’ approval for defending lawsuits,” Emblidge said in an email.

When asked what the city manager’s role in the discussion was, City Manager Georgeanne White pointed GV Wire to City Charter Sec. 803 (g), which states:

“The Council shall have control of all legal business and proceedings and may employ other attorneys to take charge of any litigation or matter or to assist the City Attorney therein.”

Coincidentally, Sec. 803 covers the role of the city attorney and what the District Attorney’s office alleges Esparza violated.

During the July 21 closed session item — three days after charges were filed — the city council learned that Esparza’s criminal defense could be covered, an extension of the information received on June 23.

A motion was made to prevent the city from covering Esparza’s criminal defense but it failed 4-2, sources say. That action was never reported publicly. Experts contacted by GV Wire were uncertain about whether such action needed to be made public.

Three conditions need to be met for a city to cover a criminal defense of an employee, including an elected leader — the alleged actions are brought on account of an act or omission in the scope of employment with the public entity; and it is determined to be in the best interest of the government entity to provide such a defense; and the employee acted without actual malice and in the apparent interests of the public entity.

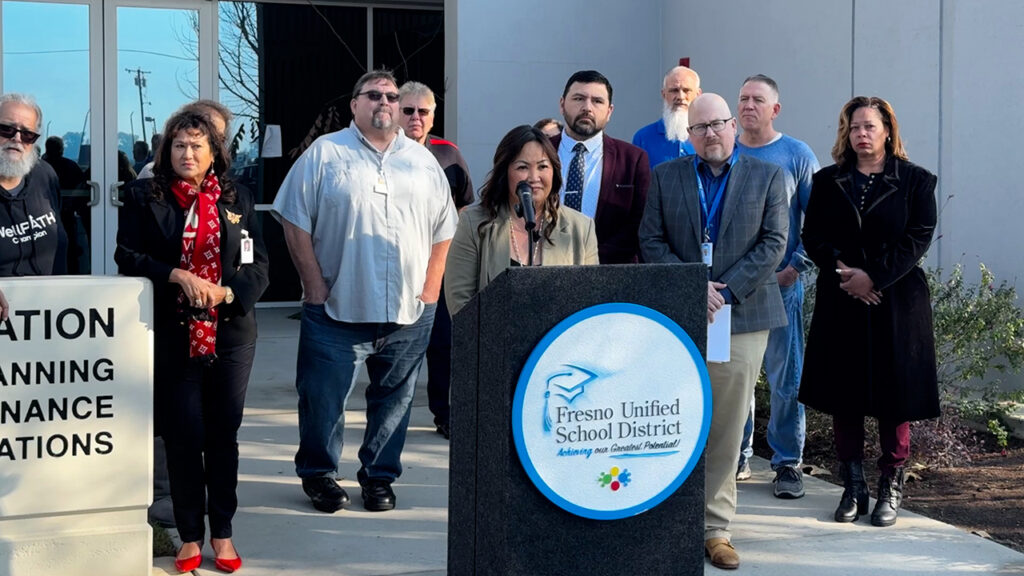

Interim City Attorney Rina Gonzales did not respond to a request for comment.

Esparza dropped his defamation lawsuit in June, in part because the city would pay for Bredefeld’s defense.

“The potential liability to the City is something that greatly concerns me because it is our belief that the lawsuit would be successful. I love our city and will not sue the City of Fresno over my colleague’s defamatory remarks. His antics have already cost enough taxpayer dollars,” Esparza said in a news release.

Transparency of Closed Session Decisions

“Assuming it was agendized and properly discussed in closed session, any vote on whether to commit the City to pay an individual’s attorneys’ fees should have been reported in open session.” — Attorney Scott Emblidge

Municipal attorney Emblidge says more transparency is needed in both reporting on any vote in closed session, and how it is listed on the agenda.

“If such a vote was taken, that issue should have been specified on the council’s agenda. It is far from clear that this issue could be discussed in closed session under the litigation exception for closed sessions,” Emblidge said. “But even assuming it was agendized and properly discussed in closed session, any vote on whether to commit the city to pay an individual’s attorneys’ fees should have been reported in open session.”

Discussing potential litigation is an exception to the open meeting act.

David Loy, legal director with the First Amendment Coalition, questions whether Esparza’s pending litigation meets the threshold to hold the discussion in closed session.

“There has to be a bona fide exposure to litigation … It can’t just be a hypothetical fear,” Loy said. “(The city council) can’t collude to pretend that there’s a fear of litigation when there’s not.”

Loy also questioned whether the city can provide legal defense based only on existing policy or law.

“If it doesn’t require a vote of the council, why is it coming for council in the first place?” Loy said. “Because all Esparza would have to do is submit the form and get reimbursed.”

Both Loy and Emblidge — neither of whom are involved in the case — were at times baffled how a vote in closed session, if taken, would not be reported publicly.