Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Retail gasoline prices last year shot to record highs in California – a spike partly related to crude oil prices – but to a level unique to the Golden State. Responding to widespread outrage, Gov. Gavin Newsom called for a special session of the California Legislature to consider imposing an excess profits tax on refiners.

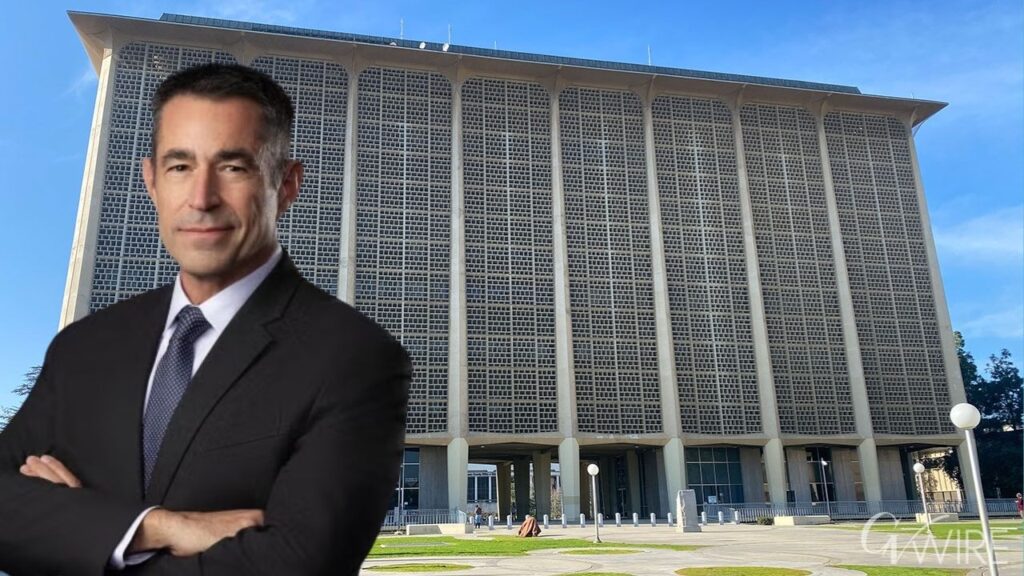

Larry Harris

Special to CalMatters

Opinion

Although founded on fairness principles, Newsom’s proposed tax will do little to address the underlying root causes of the price spikes. State elected officials instead need to shift their focus and understand the incentives for refiners to maintain their facilities and store finished products. To accelerate effective policymaking, the Legislature must facilitate research and lift the legal barriers to accessing the state’s industry data.

In general, refinery shutdowns are necessary to conduct maintenance and to address unexpected safety and quality problems. These outages largely do not impact prices since refineries typically store significant amounts of gasoline to cover potential shortages. Outside of California, many refineries produce common gasoline grades, so lost production at a single refinery rarely affects overall prices.

But in California, refineries are required to produce specially formulated gasoline grades and switch between summer and winter formulations. Since few refineries produce the state’s formulation, routine and unscheduled shutdowns can cause shortages that other refineries cannot make up. Additionally, refineries are reluctant to store substantial quantities of the current formulation when the seasonal changeover is near. These shortages cause our gasoline price spikes.

The role of these factors – and the lack of scrutiny – demonstrate that policymakers must pay close attention to refiner maintenance practices to attenuate spikes in gasoline prices.

When gasoline prices increase, producing refiners collect windfall profits. This means refiners have a strong incentive to produce during price spikes.

These incentives are strongest for refiners that operate only one refinery producing California grades. If they experience an outage, they miss out on the windfall.

But if a refiner operates two or more sites, periodic price spikes alter their incentives for maintenance. When one of their refineries goes offline, the windfall profits they obtain at other refineries offset their lost profits. The windfall profits can be so great that the refiner may make more money overall despite a shutdown.

Multi-refinery operators thus have an incentive to schedule more routine maintenance. And depending on repair costs, the windfall profits earned reduce their incentives to better maintain their equipment. If repair costs are not too high relative to maintenance costs, they will do less maintenance, and unscheduled downtime will increase.

These observations are founded on well-accepted managerial economic theory that researchers have proven in many other industries. Still, knowing that these predictions actually characterize maintenance decisions made by California refiners would be helpful to public policymakers. In particular, policymakers ought to know whether maintenance outcomes vary by how many refineries refiners operate.

To this end, I asked the California Energy Commission to allow me to examine the production data that all California gasoline refiners report monthly. Unfortunately, current law only allows the commission and its employees to examine the data. This restriction prevents academic researchers (or members of the public) from producing work that could help the Legislature and the energy commission better regulate gasoline markets.

In the meantime, agency employees should study their data to determine whether maintenance outcomes vary by how many sites a refiner operates. If they do – as I expect they will find – the commission should strengthen the incentives to keep refineries up and operating safely and, in turn, keep prices lower at the pump.

About the Author

Larry Harris is a professor and the Fred V. Keenan Chair in Finance at the USC Marshall School of Business. He was chief economist of the Securities and Exchange Commission from 2002-04.

Make Your Voice Heard

GV Wire encourages vigorous debate from people and organizations on local, state, and national issues. Submit your op-ed to rreed@gvwire.com for consideration.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Renee Good’s Relatives Speak to Lawmakers in Washington