Share

![]()

■Population forecasts for California and Fresno County predict slowed growth in coming decades.

■Local environmental and social advocates say the population trend doesn’t warrant a major investment in SE Fresno.

■Multiple studies show Fresno’s wealth is increasing. This will intensify demand for single-family homes.

Keith Bergthold two decades ago helped design an urban village for southeast Fresno. The plan called for single-family homes, affordable apartments, trails, parks, and job centers — all located close to transit.

Now, the former city planner opposes the implementation of that award-winning plan.

Why?

He fears that Fresno won’t have enough growth in coming years to justify the city’s investment in an area that largely remains farms and ranches today.

Similar stories are playing out through much of California, as its once-booming population growth has stopped — at least temporarily.

“The city should actually be assessing their ability to sustain existing services within the existing city limits based on those population projections, let alone taking the risk of investing outside this for a population that may not come,” Bergthold said in a November 2023 presentation to the League of Women Voters.

But Fresno City Councilmember Luis Chavez, whose district would encompass the area, said Fresno is one of the last affordable areas in the state. That makes it likely to attract people from other parts of the state. In addition, Fresno’s fast-growing medical sector is drawing administrators, doctors, and nurses from other states.

“We are essentially the last frontier in the state of California where people can achieve homeownership,” Chavez said. “That’s not possible for working-class individuals in the Bay Area or Southern California. So, we’re going to have a big, you know, pull factor, here from residents from all over the state. And we saw that during the pandemic.”

State Lowered its 2060 Population Forecast for Fresno County by 800,000

Bergthold now heads the Regenerate California Initiative. Four months ago, he and Fresno attorney/community activist Patience Milrod offered their interpretations of what a stagnant local population would mean for outward development before the Fresno chapter of the LWV.

“If you develop downtown, the city gets most of the (tax) money.” — Keith Bergthold, Regenerate California Initiative

While analysts predicted in 2010 that Fresno County would grow to 1.9 million people by 2050, more recent state forecasts project 1.1 million by 2060, Bergthold said in the presentation. He declined to speak on the record to GV Wire for this article.

“Fresno County is barely going to be 1.1 million in 2060,” Bergthold said during his presentation. “Ten years later — 800,000 fewer people than we were projecting.”

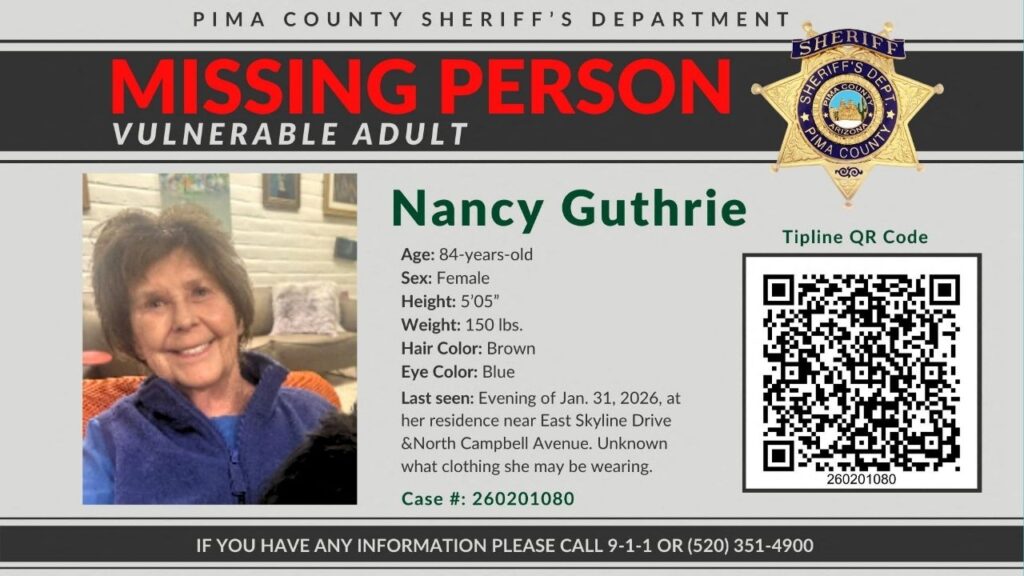

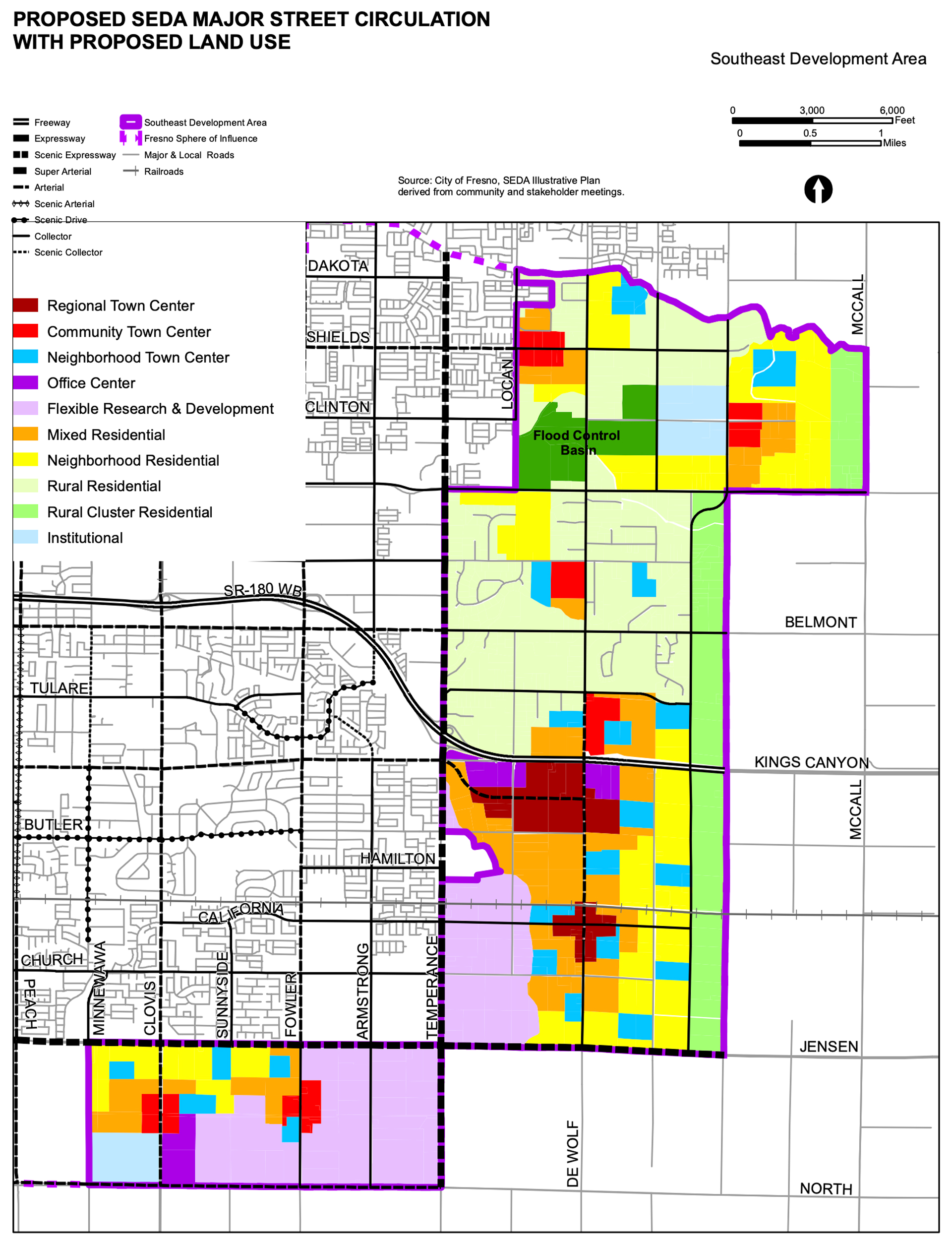

In the context of Fresno’s plan to develop southeast Fresno — called SEDA for the Southeast Development Area — Milrod and Bergthold said the necessary investment to build water and sewer connections in the undeveloped land could cost billions of dollars and would come at the expense of the city’s interior. And, if forecasts ring true, there may not be people to buy those homes, they said.

New development would also net an additional 510,791 tons of greenhouse gas emissions per year, according to the city’s environmental document, much of which can’t be mitigated.

“Not only does the environmental document not have any straight-faced mitigation, they don’t even try,” Milrod said.

Two months after the presentation, in January, Fresno Mayor Jerry Dyer and the city council called for an indefinite suspension of an environmental study into the costs of SEDA infrastructure.

Dyer cited slowing population growth as the reason for suspending SEDA.

“I am not comfortable with implementing any City-led development or capital improvements until population growth thresholds have been sufficiently addressed, and a financial model that allows private development to finance such growth has been identified,” Dyer said.

However, population forecasts are highly variable. For example, universities and job centers can attract young people to grow populations. In addition, the initial buy-in to begin SEDA is $90 million upfront, according to city estimates. That’s far below the billions cited by Bergthold and Milrod.

That’s because infrastructure investments can be made simultaneously with development.

Do Waning Population Forecasts Thwart Plans for Outward Growth?

In 2023, the California Department of Finance updated its long-term population forecast, drastically lowering its outlook for the number of births in the Golden State.

Declining birth rates, aging populations, and out-migration lead demographers to downgrade forecasts for year-over-year population growth in Fresno County. The state’s latest forecast estimates that Fresno County will have average annual growth of .2% through 2060.

It’s that lack of new blood that doesn’t justify expanding outside the city’s boundaries, Bergthold said. Out where Fresno becomes Sanger, developers have eyed building in SEDA. But getting the necessary water and sewer to accommodate 9,000 new homes in that area could be a $1.5 billion total investment. Or it could be as high as $3 billion, according to Bergthold.

It’s difficult to figure out an exact figure. Dyer and the Fresno City Council’s suspension of the SEDA plan keeps their cost breakdowns hidden from public view.

To pay for infrastructure, cities need to bond for those costs. Impact fees from developers as properties are used to pay off the bonds. The city receives those fees as residential and commercial properties are built and sold.

But, if those homes don’t sell, cities are on the hook for the bonds. That could lead to lower bond ratings if delinquencies occur. Paying for outstanding debt could also mean smaller budgets for police, fire, and road services.

City revenue estimates today show the challenges in getting police and fire out to fringe areas.

“They could end up with $1 billion or $2 billion of stranded assets they can’t pay for,” Bergthold said.

How Accurate Are Projections?

Forecasts are fluid and highly variable.

“I represent an area that has a large chunk of immigrants that come here and make a better life for themselves and those usually don’t get counted.” —Luis Fresno City Councilmember Luis Chavez, a SEDA advocate

Mike Prandini, president of the local Building Industry Association, says the state Finance Department forecasts are hard to believe.

A .2% annual growth is about 1,100 people.

“Do you believe that in a city the size of Fresno? That they’re only going to grow by 1,100 people in a year?” Prandini said.

In 2021, the Fresno Council of Governments predicted that the county’s population would reach 1.2 million by 2050 — a .75% annual growth from 2020 to 2050.

Based on that forecast, the state Department of Housing and Community Development called for Fresno COG to account for 58,298 new units. The city’s required share is 36,866 units. The Department wants 43.1% of those units built for above-moderate-income households.

Fresno COG’s interim president Robert Phipps said the organization is now deferring to the state Finance Department’s latest outlook. It won’t be until the next housing cycle in eight years that Fresno County’s housing goals will change, Phipps said.

Chavez says that the 2020 Census may have missed the mark significantly in his district because of a large immigrant population.

“I represent an area that has a large chunk of immigrants that come here and make a better life for themselves and those usually don’t get counted,” Chavez said.

Cities Can Grow Despite Projections

But even the stagnant population outlook is not everywhere. The state Finance Department predicted a remarkable 16.8% growth for Merced County by 2060.

Demographer Andres Gallardo with the stateFinance Department said much of that growth can be attributed to UC Merced attracting young people. Younger people tend to have bigger families, Gallardo said.

Fresno County is already losing growth to other counties, especially to south Madera County.

Just as a city can overextend itself in debt, not planning for enough growth can lead to stagnancy, said Prandini. Retailers look for household incomes and rooftops before they come or expand in an area. Major employers look for similar factors when they choose sites.

Not building for the future can become a self-fulfilling prophecy for a city.

“If you don’t plan for it and do the infrastructure to get people there, when the population does come, you have nothing,” Prandini said.

Housing Construction Statewide Lags, Especially in Fresno

California’s 111,221 new housing permits in 2023 were the third-highest in the country, according to data website Point2Homes.com. However, that building rate continued a two-year decline amid the state’s much-chronicled housing crisis.

Homebuilders and real estate agents have long cited low housing inventories for causing California’s sky-high real estate prices.

Nationwide, housing starts and issued permits dropped by 9% and 11%, respectively, likely a reaction to mortgage interest rate increases.

In California, the number of permits issued dropped by 6%.

However, Fresno ranked No. 23 nationwide among metros with a 12.4% drop in issued permits. And, Fresno lagged behind only San Francisco’s 32.3% year-over-year drop for new permits in California.

Point2Homes attributed the decline in the state to not only dwindling demand, attributed to high prices and mortgage rates, but low builder confidence, driven by rising construction costs.

“Completions are increasing year-over-year, so completed units aren’t yet impacted by falling permits, but they might be in the not-so-distant future,” said Carmen Rogobete, communications strategist with Point2, in an email.

“Even at this point, buyers are struggling with low inventory and high mortgage rates. So, if the number of new homes were to also start dropping, it would affect them even more.”

SEDA Envisioned as a Modern Town

When planners, including Bergthold, developed SEDA, they envisioned a 9,000-acre mega development with not just housing, but job centers as well.

When fully built out — a process that could take decades — it could bring 45,000 homes and 37,000 jobs, according to the plan’s EIR.

Being mostly ag land, SEDA’s development would require landowners to be on board. That would mean selling family farms to builders to carry out the vision.

Many landowners in the area do not want development. They formed an opposition group, Fresno Southeast Property Owners.

Others, according to Fresno County Supervisor Nathan Magsig, whose district encompasses much of SEDA, see it as an opportunity to get out of farming.

Medical Sector Drives Greater Fresno Wealth

In the heart of ag country, healthcare has more recently driven job and income growth.

Herndon Avenue has exploded with medical offices and, over the past 10 years, the number of typically high-paying healthcare jobs increased by 45.5% to 78,300 through December 2023.

Fresno COG expects wealth to climb further. And, analysts expect the number of households earning less than $50,000 to decline significantly. Households with income brackets of more than $50,000 will climb at rates greater than 60%, according to COG data.

Households earning more than $150,000 will grow by 68.9% from 2020 to 2050, the second-highest rate among income brackets. The number of households earning from $75,000 to $99,999 is expected to grow by 69.7%.

The state wants 43.1% of housing built for above-moderate income families — the biggest share of housing. For many in that income category, that means homes with backyards and pools.

134,000 Units of Infill Available

Of the 63,000 acres in Fresno, 8,214 is vacant, or about 14%, according to a 2019 city study. Much of that includes large swaths of agricultural land west of Highway 99.

That acreage could create 134,693 new units, of which about one-third could be single-family homes.

Bergthold said in the presentation those units could account for any incoming population and not overextend a city’s finances. It could also help shape the future of Fresno.

Planners and environmental advocates often look to dense, high-rise buildings for new units, the kind suited for infill development. Having people close to one another limits the environmental impact of building outward.

Having high concentrations of people also encourages businesses to come to an area. Public transportation thrives more in dense populations in the eyes of planners.

Already, on Blackstone Avenue from McKinley to Shields avenues, the city’s vision is taking hold. Affordable housing complexes The Arthur @ Blackstone and The Link opened in the past few years, bringing 41 and 88 units, respectively.

Building in the city’s interior makes fire and police services more financially feasible because of tax-sharing agreements.

“If you develop downtown, the city gets most of the (tax) money,” Bergthold said.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Renee Good’s Relatives Speak to Lawmakers in Washington