Share

Assembly Bill 386 sailed through the Assembly Judiciary Committee last week on a unanimous vote with virtually no discussion about its provisions.

The measure also received express treatment a few days earlier from the Assembly committee that deals with public employee matters.

Given its cavalier handling, one might think that AB 386, carried by Assemblyman Jim Cooper, an Elk Grove Democrat, is just another minor change in law. In fact, however, it would allow the financially shaky California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS) to semi-secretly lend out untold billions of dollars by exempting details from the state’s Public Records Act.

Dan Walters

Opinion

Bill Would Allow Direct Lending Without Disclosing Loan Details

Potentially it opens the door to insider dealing and corruption in an agency that’s already experienced too many scandals, including a huge one that sent CalPERS’ top administrator to prison for accepting bribes.

CalPERS, which is sponsoring the bill with support from some unions and local governments, claims that the exemption is no big deal since the money it lends through “alternative investment vehicles” such as venture capital funds and hedge funds is already partially exempted from disclosure.

However, there is a big difference. Using outside entities to invest means they have skin in the game. Direct lending by CalPERS means that its board members, administrators and other insiders would be making lending decisions on their own without outside scrutiny.

CalPERS’ rationale is that using alternative investment partners is costly because of their fees, and that direct lending could potentially result in higher earnings. However, it says, disclosing loan details would discourage many would-be borrowers from seeking CalPERS loans, thus limiting potential gains.

CalPERS Blames Shortfall on Pandemic

Underlying that rationale is that CalPERS’ $440 billion in assets are, by its own calculations, only about 71% of what’s needed to make pension payments that state and local governments have promised their workers. It has ratcheted up mandatory “contributions” from its client agencies to close the gap, but it’s also been chronically unable to meet its self-proclaimed investment earnings goal of 7% a year.

During the fiscal year that ended last June 30, CalPERS saw a net return of 4.7%, blaming the shortfall on the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“What started out as a health crisis turned into an economic crisis and severely affected investors everywhere, including CalPERS,” Yu (Ben) Meng, CalPERS chief investment officer, said at the time.

One sub-par year would not be cause for alarm, but CalPERS officials have repeatedly said that meeting the 7% goal over time would be impossible without getting more aggressive in its investments.

Meng Another Example of Potential Pitfalls

Meng was brought aboard to juice up investment strategy but shortly after reporting disappointing 2019-20 results was forced to resign because he failed to reveal his personal investments in a New York financial firm, Blackstone Group, with whom he had placed $1 billion in CalPERS funds.

The Meng situation illustrates the perils should AB 386 become law and CalPERS officials be allowed to loan money to corporations and individuals without having to disclose all-important details.

The potential pitfalls were pointed out in an extensive analysis of the bill by the Judiciary Committee staff. It mentioned the Meng case as well as the scandal that sent chief executive Fred Buenrostro to prison for taking bribes from Alfred Villalobos, a former CalPERS board member who became a “placement agent” for hedge funds. Villalobos committed suicide rather than face prosecution in the scandal.

One might think that members of the two Assembly committees that rubber-stamped AB 386 would have at least discussed those scandals and the potential downside. But they couldn’t be bothered to do their jobs.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

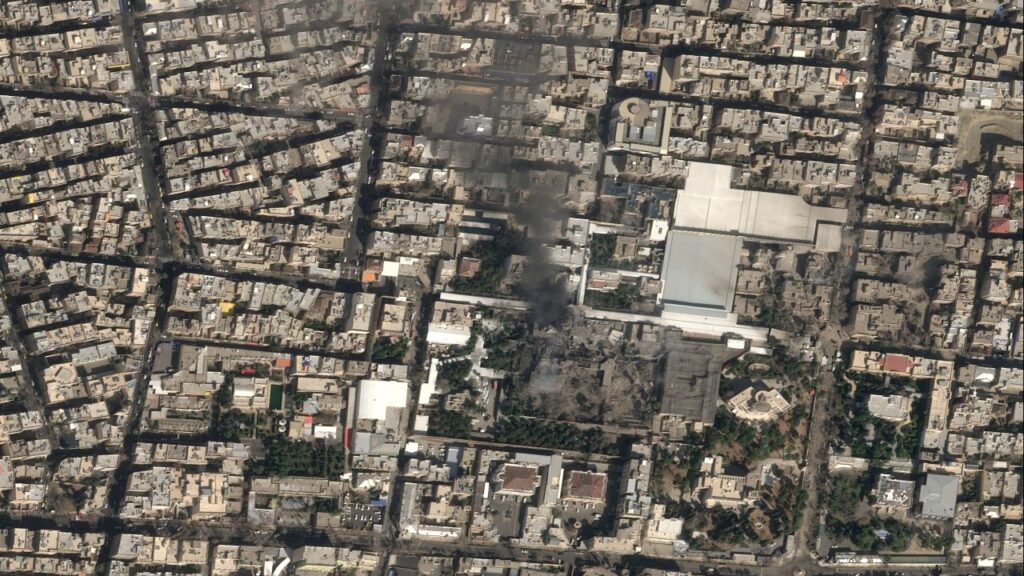

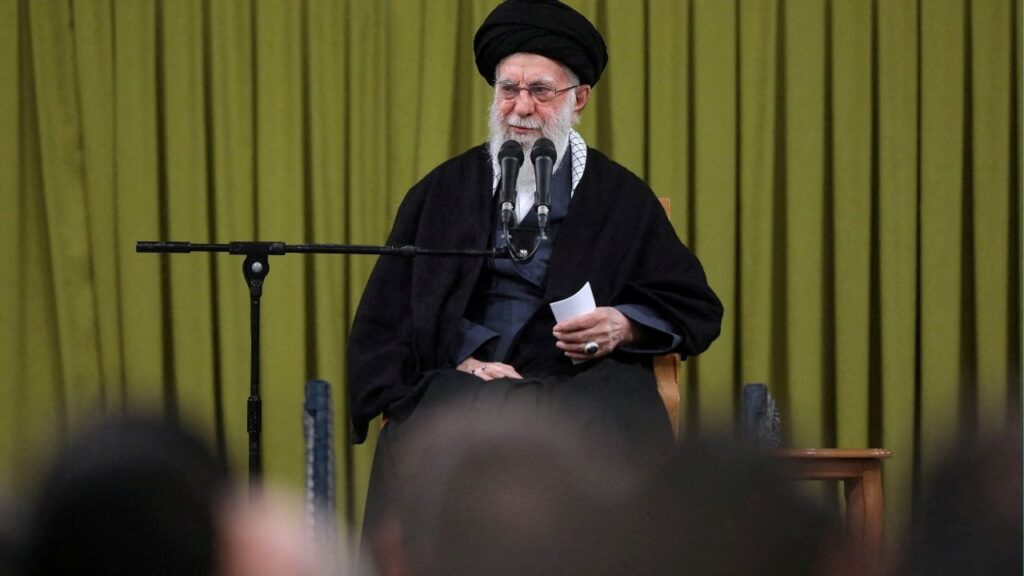

Ayatollah Khamenei Reported Killed Following US-Israeli Airstrikes