Share

Since the coronavirus swept into Silicon Valley last spring, Denise Russell’s race to save her San Jose salon has stretched into a marathon. It started with a $103,020 Paycheck Protection Program loan. Then came a federal small business Economic Injury Disaster Loan for $159,000. Now, she’s applying for a $15,000 state grant and another PPP loan — all while fighting the state for delayed unemployment payments.

Lauren Helper

CalMatters

“They make it so complicated,” said Russell, whose Special FX Salon & Day Spa was closed for seven months in 2020. “They’re constantly changing the rules. I mean, it’s a nightmare.”

Russell spent thousands on medical-grade sanitizer and a parking lot salon, but she only brought in around $350,000 of the more than $1 million in revenue she expected last year. Across the state, business owners staring down similarly daunting numbers warn of an “extinction event” that could claim a third or more of small businesses, with service sector employers and those owned by women and people of color at highest risk.

Amid winter closures triggered by record virus cases, California kicked off an unprecedented small business rescue plan. Federal loan programs have already injected more than $83 billion into California businesses, and the state is rolling out its own grants, loans and tax relief. Still, business owners warn that it’s not enough, especially after widespread technical glitches and confusion about eligibility, programs that have at times favored bigger companies and nagging questions about interest or funding restrictions.

“These are unheard-of numbers when it comes to cash for small businesses,” said Mark Herbert, vice president of California operations for national advocacy group Small Business Majority. “But it’s also important to understand the scale of the need. ”

A $4.5 Billion Relief Plan

Beyond high-profile clashes over pandemic reopening rules is a fundamental question that has vexed state and federal officials: whether to inject more direct aid now, hopefully staving off mass commercial evictions and bankruptcies, or focus on longer-term economic stimulus.

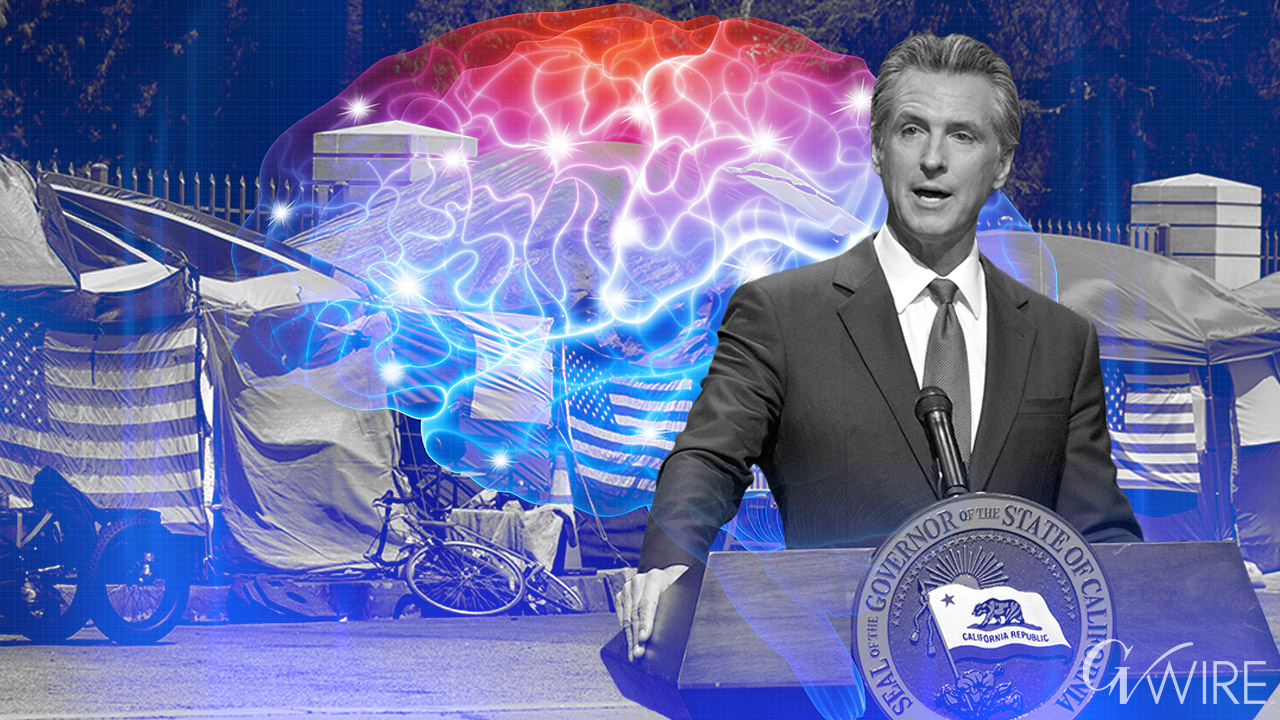

With his $4.5 billion Equitable Recovery for California’s Businesses and Jobs budget plan, Gov. Gavin Newsom aims to do both. Among the proposals: $575 million in cash grants, $630 million in tax relief and $135 million in low-interest loans. The administration included $1.5 billion for zero-emission vehicles and $500 million for housing development, contending those funds would spur clean-energy and construction jobs

“Small businesses are the backbone of our economy,” Newsom said during a Jan. 5 virtual address. “I recognize the headwinds. I recognize the stress. I recognize all that you have been put through over the course of the last year.”

California’s approach has national implications. Janet Yellen, a member of Newsom’s economic recovery task force, is President Joe Biden’s nominee for treasury secretary. Isabel Guzman, director of California’s Office of the Small Business Advocate, is Biden’s nominee to lead the U.S. Small Business Administration.

Back in Sacramento, economic recovery efforts will be helmed by Newsom’s new senior business adviser and Clinton administration alum Dee Dee Myers. State lawmakers are also fighting for additional small business aid. Sen. Anna Caballero, a Democrat from Salinas, has championed a larger $2.6 billion small business grant program with SB 74.

“I’m a big supporter of community aid right now,” Caballero said. “Part of that is we need to get people back to work.”

Mind the Gaps

One challenge 10 months into the pandemic is that no one knows for sure how much damage has already been done.

From February to April, 3.3 million small businesses nationwide vaporized, according to a Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research analysis — a 22% overall drop, but a 41% drop for Black-owned businesses, 32% for Latinos, 26% for Asians and 25% for women. In California, 30% of small businesses remained closed in November, and “thousands” shut down permanently, according to a report by state oversight agency the Little Hoover Commission.

Last spring, millions of businesses scrambled to get a piece of the $669 billion federal Paycheck Protection Program, which doled out 617,216 loans totaling $68.3 billion in California, Small Business Administration records show. It was a frenzy that strained the state’s hundreds of local small business groups and highlighted existing racial disparities in access to capital, as well as costly tools like online sales software to stay safe and competitive in a pandemic.

“We had an influx of people reach out that needed just the fundamentals,” said Dene’ Starks, education director of Elk Grove’s four-person Black Small Business Association of California. As big banks fast-tracked applications for the Los Angeles Lakers and billion-dollar tech startups, her group helped small businesses get federal tax numbers and open bank accounts.

Brian Rauso managed to cut through the red tape for a PPP loan worth $82,250 for his Green Cheek Brewing Co. in Orange County. The company was still forced to lay off dozens of its 49 employees after opening a second location in January. A $1,000 grant from Orange County helped build an outdoor patio this summer, and he’s got a $150,000 emergency loan in reserve.

With the businesses closed again as the virus rages in Southern California, Rauso worries government aid is “too little, too late.” The bigger issue, he said, is when he can reopen, and whether the business will still be bound by highly specific state rules that require breweries to serve full meals to operate. For now, Green Cheek has indefinitely shelved plans for a third location, and Rauso has watched three former employees move out of state for lower costs of living.

“COVID, unfortunately, it’s like turning the lights on in the middle of the night and seeing what’s really going on,” Rauso said. “It’s exaggerated all the problems that have been there.”

New Loans

As small business owners try to keep their heads above water, policymakers, philanthropists, attorneys, banks and academics have come together behind the scenes to try to fill gaps in patchwork aid programs. It’s a tall order, especially to reach the state’s smallest businesses. But if it works, those involved say it could change the way small business lending is done in California and kickstart new jobs as the state economy recovers.

The public-private California Rebuilding Fund launched late last year is small by the scale of recent federal loan program, but it’s 4.25% interest loans are designed to be paid out by local Community Development Financial Institutions that can reach more small businesses. A separate $35 million Dream Fund in Newsom’s proposed budget would offer additional capital to entrepreneurs from underrepresented groups to start new businesses.

“We need to try to stem the bleeding. But we also wanted to start planning and thinking about, ‘How do we identify long-term strategic priorities?’” said Herbert of Small Business Majority, who helped develop the Rebuilding Fund. “That’s a piece of infrastructure that’s not just built for the emergency, but has tremendous implications in the future.”

Unemployment numbers and new business starts in the coming months will test which programs are making a dent for small businesses. For now, with her San Jose salon still closed, Russell is among those branching out. She’s already raised money from two private investors to start the wine company she always imagined at her home in Morgan Hill.

“I’m a workaholic. I had to figure out how to divert my negative energy,” she said. “That would have never happened had the status quo continued.”

The author wrote this for CalMatters, a public interest journalism venture committed to explaining how California’s Capitol works and why it matters.

About the Author

Lauren covers the California economy for CalMatters. Her past stories have been published by the New York Times, the L.A. Times, the Guardian and others.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

US Conducts Lethal Operations in Ecuador, Military Says

Justice Dept. Pushes for Charges Against Cuban Leaders