Share

A change to a California law on food waste could have devastating impacts on the state’s climate goals. In our collaborative approach to tackling climate change and reducing global greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), we have discovered a secret weapon. The ability of our dairy and beef cattle to upcycle organic waste is a phenomenal tool that reduces landfill waste and therefore decreases methane gas emissions.

Frank Mitloehner

Opinion

According to the EPA, landfills are the third-largest source of human-related methane emissions, accounting for about 15% of all U.S. methane emissions in 2018. Twenty years ago, inedible agriculture byproducts (e.g., nut hulls and shells, citrus pulps, pineapple tops, cotton seeds, and corn husks) and waste from businesses such as restaurants and grocery stores, were thrown away and sent to landfills. There, the organic waste would decompose and release methane as a result of that process.

Nowadays, our society looks to the humble cow for nearly complete disposal of this inedible waste. The rumen (stomach) of the cow is incredible at breaking down these tough materials and upcycling them into edible protein in the form of dairy products and beef for millions of people. In fact, 86% of global livestock feed comes from byproducts that are indigestible by humans. Unfortunately, AB 2959, a bill currently moving through the California State Senate, could severely impact the state’s ability to upcycle some of these waste byproducts — taking the current inventory of GHGs to a potentially higher level.

Legislation Would Send More Organic Waste to Landfills

The bill proposes allowing local governments to dictate who transports these waste products and minimizes choices in local distribution vendors. As a result, Californians would have fewer opportunities to fight climate change and keep organic waste out of landfills. Restaurants, grocery stores, retail, and manufacturing businesses would have no choice as to where to send their scraps, discarding a valuable opportunity to sustainably contribute to the food chain. Currently, many of these businesses sell the byproducts of their bakery waste, their citrus pulps, and their distillery waste directly to farmers to feed their cattle.

In 2016, under former Sen. Ricardo Lara’s leadership, the Legislature enacted SB 1383, which mandates a 40% reduction of methane below 2013 levels by 2030. This includes methane from landfills, refrigerants, black carbon sources, and livestock. Upcycling of human-inedible feed plays a significant role in helping the state achieve this methane reduction goal. The state also has a law on the books stating that local governments are responsible for managing solid organic waste — unless the waste is a byproduct from food or beverage manufacturing. AB 2959 changes this law, specifically targeting waste from businesses such as restaurants and grocery stores.

AB 2959 May Add to Food Waste Problem

Allowing local governments to take control of these byproduct-transportation pathways threatens to trash a well-tuned process with a myriad of food and environmental benefits. In addition, it may create new environmental problems and further contribute to the vast food waste cycle that our communities are desperately trying to break.

About 18% of materials that go into California landfills is wasted food. Nationwide, about 30% to 40% of the food supply is wasted. Let those numbers sink in. They’re truly unacceptable.

This potential disruption could be hugely detrimental to our state’s efforts to lead the fight against climate change. In curbing the role cattle play in keeping solid organic waste from heading into landfills, we may add to the climbing food waste problem across the United States.

California dairy and beef farmers strive to feed us while lessening their impact on the climate, yet this bill threatens those efforts and the Golden State will not be better for it. For that reason, AB 2959 is what needs to be thrown out.

About the Author

Dr. Frank Mitloehner is a professor and air quality specialist in cooperative extension in the Department of Animal Science at UC Davis and the director of the CLEAR Center.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

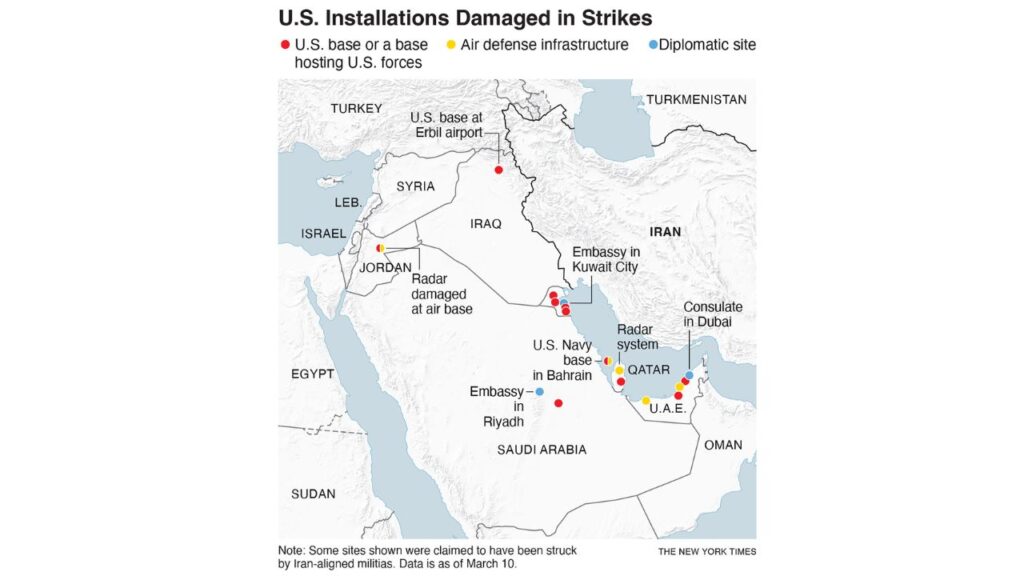

At Least 17 US Sites Damaged in War With Iran, Analysis Shows

Clovis Police Arrest 32 Drivers for DUI in February