Share

Periodically, owners of major league sports teams change game rules and in doing so they inevitably affect the games’ outcomes, purposely or not.

Politics are no different. Changing the rules of campaigning, voting and other political procedures affects election results.

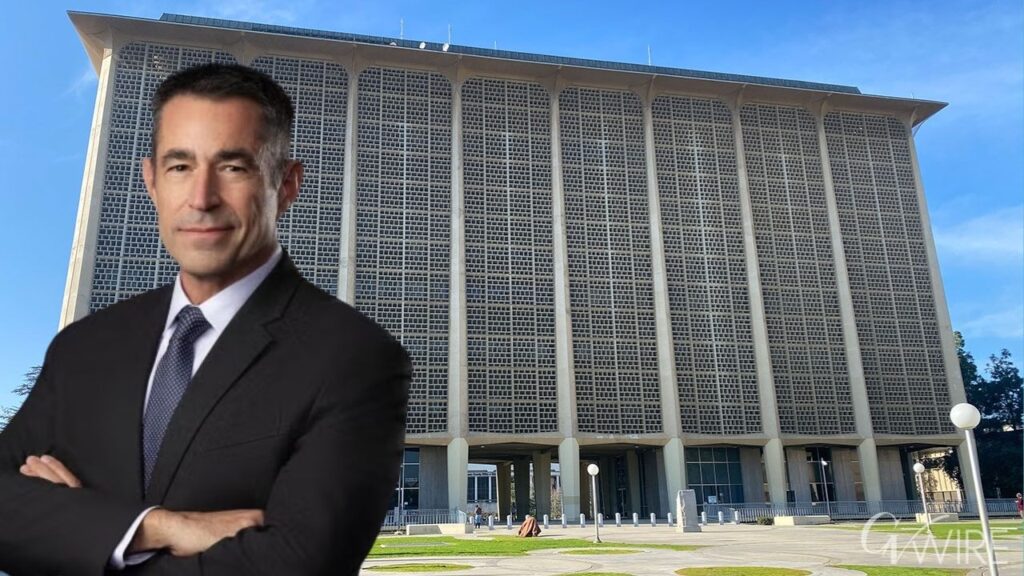

Dan Walters

Opinion

We saw an example of that adage this year. Loosening voter registration requirements, allowing or disallowing ballot harvesting and, in some states, shifting from in-person voting to vote-by-mail affected voter turnout, altered the composition of the electorate and thus ultimately had an effect on what or who won or lost.

Obviously, writers of rules — federal and state legislators, mostly — have a motive in changing them to benefit themselves, their parties and their allied interest groups.

That’s why, for instance, the national Democratic Party poured untold millions of dollars into state legislative campaigns. The campaign’s avowed goal was altering the partisan balance of statehouses, now mostly Republican, to affect how congressional districts are redrawn after the 2020 census, but it largely failed.

Hertzberg Apparently Believes That the Change Would Decrease the Chances of a Successful Referendum

Two constitutional amendments introduced in the California Legislature’s newly convened session attest to the continuing desire of politicians to change political rules and thus outcomes.

Senate Constitutional Amendent 1, submitted by Sen. Bob Hertzberg, a Democrat from Van Nuys, would flip how referenda — measures to overturn laws passed by the Legislature — are submitted to voters.

Currently, an interest group opposed to a new law can challenge it by collecting enough signatures to place a referendum on the ballot. Voters are then asked to either validate the new law by voting “yes” or repeal it by voting “no.”

Hertzberg wants a “yes” vote to repeal the new law and a “no” vote to keep the new law in place.

Is the current procedure a little confusing? Yes, particularly since the referendum process is only occasionally used. But it’s doubtful that SCA 1’s change would be less confusing.

Hertzberg apparently believes that the change would decrease the chances of a successful referendum because if voters are somewhat undecided or confused about the underlying issue, they are more likely to vote “no.”

He introduced SCA 1 a month after his landmark law abolishing cash bail for criminal defendants was overturned by a referendum, Proposition 25, sponsored by the bail bond industry. Voters marked nearly 55% of their ballots “no” on Hertzberg’s bail bill.

When You Change Political Rules, You Likely Change the Outcome of the Political Game

Proposition 25 is widely seen as a template for other referenda by business groups adversely affected by laws passed by a liberal Legislature.

Senate Constitutional Amendment 3, offered by Sen. Ben Allen, a Redondo Beach Democrat, would make a huge change in recall elections.

Currently, when enough signatures are collected to seek the recall of an elected official, such as then-Gov. Gray Davis in 2003, the issue is placed before voters in two simultaneous ballot measures. One is on the recall itself and the second is to elect someone to replace the ousted officeholder if the recall is successful.

With 135 candidates on the second ballot, action movie star Arnold Schwarzenegger succeeded Davis with about 48% of the vote.

SCA 3 would maintain two ballots but would automatically place the targeted officeholder on the second ballot as a candidate with a good chance to immediately reclaim the office. In effect, someone could be ousted from office by a majority of voters but then recapture it with an easier-to-achieve plurality vote.

It’s probably not a coincidence that Allen introduced SCA 3 as a campaign to recall Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom seemed to be gaining momentum.

When you change political rules, you likely change the outcome of the political game, just as in football or baseball.

[activecampaign form=19]RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Renee Good’s Relatives Speak to Lawmakers in Washington