Share

Cargo ships wait on the Pacific Ocean, idling for days if not weeks. The Biden administration is trying to fix the supply chain to get goods into nearly every aspect of retail America.

Is the supply chain problem getting goods out of California’s ports because of a lack of truck drivers?

Maybe.

Who’s to blame?

It depends on who you ask. GV Wire spoke with several trucking industry experts about the supply chain problem. Everyone seemed to have a different answer.

A Biden administration solution is opening the ports 24/7.

“The pandemic laid bare with its increased volumes and with its different buying patterns… it laid bare a system that really needs to be modified. And the way we can do that in the short term together is to move toward more 24-7 operations,” Biden’s port envoy John Pocari said last week.

The Port of Oakland says it can handle the container load — even if those items need to be trucked to Southern California warehouses.

Trucking Industry Divided on Shortages

“There actually isn’t a truck driver shortage. That’s a red herring being put off by many in the supply chain to blame shift.” — Joe Rajkovacz, WSTA

“There actually isn’t a truck driver shortage. That’s a red herring being put off by many in the supply chain to blame shift,” said Joe Rajkovacz, an executive with the Upland, CA-based Western States Trucking Association.

Rajkovacz analysis puts him at odds with others in the trucking industry. He questions the motivation of groups like the American Trucking Association, which say there is a trucker shortage.

The ATA did not respond to GV Wire’s request for comment, but did post information on its website acknowledging a driver shortage. The group cites “aging driver population, increases in freight volumes and competition from other blue-collar careers” as the reasons.

“What they’re really talking about is a driver turnover issue. And of course, they want access to even cheaper labor. They certainly would like to see the ability of foreign drivers to come into the U.S.,” Rajkovacz said of ATA’s position. He called the use of foreign drivers “illegal.”

Teamsters: Not a Driver Shortage, It’s a Union Driver Shortage

“The problem with the supply chain isn’t a shortage of truck drivers: it’s a shortage of good, union jobs.” — Ron Herrera, Teamsters

The Teamsters, the union representing truck drivers, says drivers are being exploited.

“The problem with the supply chain isn’t a shortage of truck drivers: it’s a shortage of good, union jobs. Trucking companies are raking in more money than ever before and it’s shameful that they’re choosing to contribute to the problem instead of supporting dignified trucking jobs with livable wages that get cargo moving,” said Ron Herrera, the Teamsters port division director.

The backlog at the ports is being felt throughout the line — a lack of space at the ports to store containers to a shortage of chassis where containers are loaded.

“(They) are all having devastating effects impacting wait times and affecting how many loads drivers are able to move (which in turn means they bear the real burden because most are paid by the load, not the hour). Drivers are currently spending increased wait times — without the ability to exit their trucks, go to the bathroom, or access food. Being a misclassified port truck driver has been compared to indentured servitude,” Herrera said.

Fresno Truck Drivers: Where are They?

“We’re just having a terrible time. Matter of fact, we’re turning work down every day and we’re only taking care of our prime, good customers.” — Dale Mendoza, truck company operator

Dale Mendoza operates Quali-T-Truck Service in Fresno, which ships mainly industrial parts on flatbed trucks. He once operated 50 trucks. He is now down to 10.

“The reason we did that about a year and a half ago is because we’re so short of drivers,” Mendoza said.

“We’re just having a terrible time. Matter of fact, we’re turning work down every day and we’re only taking care of our prime, good customers that have been with us, the loyal customers that have been with us for years,” Mendoza said.

Recruiting young drivers is one of the problems, Mendoza says.

“The young people are just not wanting to get in the trucks and drive. As long as I’ve been in the business for many years, it’s a great career path,” Mendoza said.

Drivers could make nearly $50,000 a year, working five days a week driving Mendoza’s trucks. Benefits are included, he said.

“We can’t find the warm bodies. The ones that we do find, they’re very inexperienced,” Mendoza said.

Mendoza told a story about a potential hire telling him he could make more selling drugs and on unemployment.

“I said, ‘Get out of my office… what are you, nuts?’ ”

Added Mendoza: “I’ve lost all the incentive to get bigger or hire more people, which I can’t. There’s nobody out there.”

Mendoza said he is also having his drivers poached by the likes of Walmart and Target.

Truck Driving School Offers Optimism

Everett Yockey is the operations director and chief financial officer at the Central Valley-based Advanced Career Institute.

He blames fear of COVID among other reasons for a shortage of new drivers. That, in turn, has caused problems manufacturing trucks, truck parts, and even getting appointments at the DMV.

Yockey has seen environmental and labor concerns push trucking companies out of California.

“Fuel prices in California is a huge issue. Fuel is $2 higher in California than it is the next state over,” Yockey said. “They’re all going to the docks, but no one’s unloading the docks. It’s like the perfect storm, only the worst storm.”

There are signs of optimism, though. Things are picking up for Yockey’s school. He has 400 students, back to pre-COVID levels.

“Numbers are increasing because (potential drivers) see the demand and pay is up. It is the highest we’ve ever seen in the industry for new drivers. So the demand is up. Now it is a matter of getting them out,” Yockey said.

He currently has 225 appointments for the DMV. Last year at this time, he had 16.

A Port Problem

Most data shows traffic at the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports has nearly doubled since the depth of the pandemic.

Joe Rajkovacz, with WSTA, says most of the drivers from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach would carry cargo back and forth to the Inland Empire — perhaps a three-hour round trip, including “dwell time.” That could be up to three or four trips a day. But, drivers are making only one trip.

“It’s the marine terminal operators that have caused the jam up,” Rajkovacz said. “It’s a sh*t-show what’s going on right now.”

Terminal operators lease out the space from the ports, run by the respective city governments of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

“(Private operators) making huge money right now, with the dysfunction charging truckers to merge and detention fees. It’s not even a perfect storm, it’s almost criminal what’s going on within our port community right now,” Rajkovacz said.

Mendoza said he used to make runs to the ports, but no more.

“We won’t do anything off of the ports anymore because the time constrictions to load or unload at the ports, it’s prohibitive,” Mendoza said.

One of the reasons was a mitigation charge for trucking at the port from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m.

“We always went in after five o’clock so that I didn’t have to pass the mitigation charge onto our customers. We kind of eliminated going in in the daytime,” Mendoza said.

The Pacific Maritime Association, an industry group representing terminal operators, did not respond to GV Wire’s request for comment. The Port of Los Angeles would not take direct questions but pointed to a teleconference hosted last week by port officials.

“The ability to have enough chassis, enough truck drivers to actually make the operations work at the port is one limitation as well that that I think we’re all paying very close attention to,” said John Pocari, the U.S. Port Envoy.

Port of Los Angeles Executive Director Gene Seroka also identified a lack of truck drivers as a problem. There is an estimated shortage of 30,000 drivers nationwide. He pegged the annual attrition rate at 20%.

“We need to rethink the entire professional opportunity for careers in truck driving. (We need to) look at compensation, benefits, how we reward, how we attract, retain and recruit truck drivers as a profession is key in front of mind to all of us in the supply chain. Much work ahead there,” Seroka said.

Rajkovacz isn’t buying driver shortages as a problem at the ports.

“They’re full of it. Absolutely full of it. If you let these drivers at the ports, all at Long Beach work efficiently, believe it or not, you won’t have a problem,” Rajkovacz said.

California Labor Law Awaits SCOTUS Decision

The trucking industry awaits a U.S. Supreme Court decision to hear its challenge to California’s AB 5. Challengers to the law say it could decimate the trucking industry even more.

“This potentially could end their ability to legally work in the state of California,” Rajkovacz said. His group, Western States Trucking Association, filed an amicus brief.

AB 5 is the 2018 California law that classified many independent contractors as employees. That change meant employers would have to provide benefits and be subject to other labor laws.

The California Trucking Association was the main plaintiff in the lawsuit. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the state. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court, where the decision to accept the case has not yet been made.

In the meantime, enforcement of AB 5 is on hold until the high court adjudicates the case.

Herrera, with the trucker’s union, hopes the Supreme Court denies the case or rules in the state’s favor.

“Rampant misclassification has been a growing issue during the pandemic and is even more critical now as drivers are forced to navigate miles-long backups at the ports and along the supply chain,” he said.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

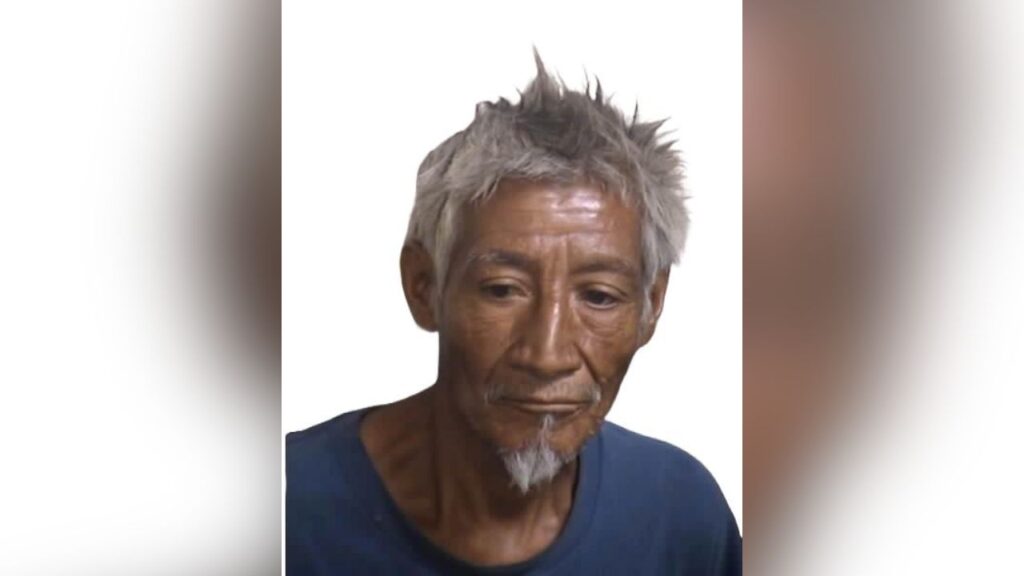

Fresno County Authorities Seek Relatives of Deceased 85-Year-Old

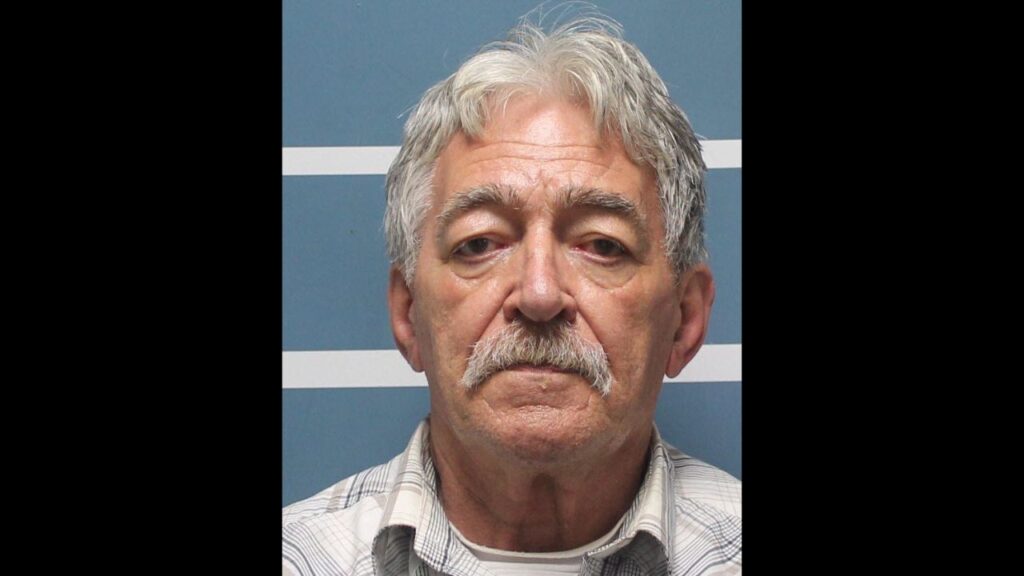

Visalia Man Sentenced to Life for Crimes Against Child