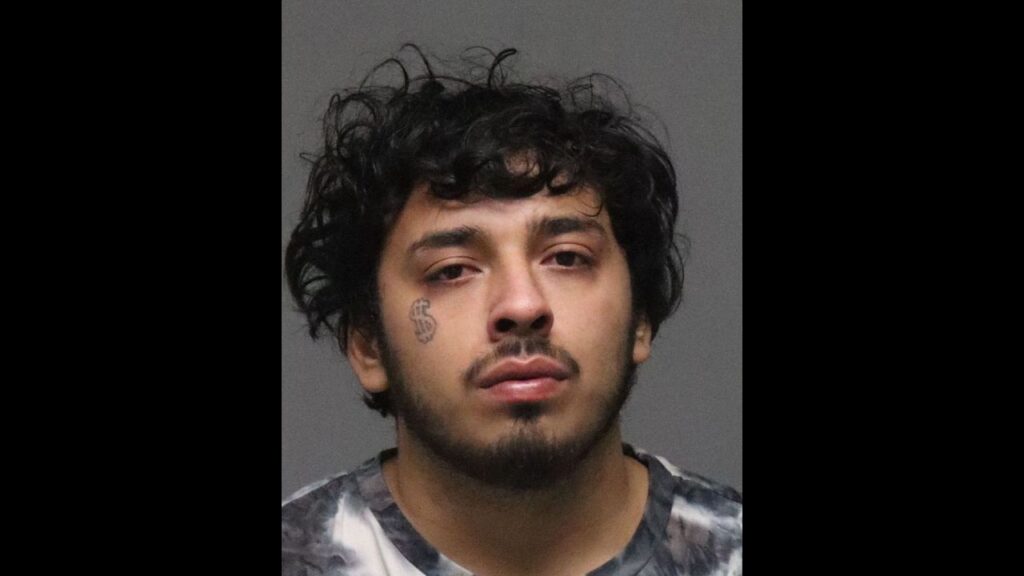

Farmworkers harvest banana peppers at a farm near the town of Helm in western Fresno County, July 1, 2025. (Larry Valenzuela/ CalMatters/CatchLight Local)

- The challenge for Californians in 2050 will be one of imagination: to see themselves as inheritors of a compromised but still resourceful California

- Success will require mastering new technologies, better teamwork, and recognizing what we have squandered.

- As hard as it will be to realize, the California we deserve is possible.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This commentary was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

One hundred and seventy-five years ago, our state was the prize in an unjust war whose aim was to extend slavery beyond the plantations of the South to the valleys of California. Fifty years later, those valleys were dominated by corporate agriculture (wheat, cattle, cotton and oranges) and controlled politically by railroad interests.

D.J. Waldie

Special for CalMatters

Opinion

By 1950, the future of California was in the hands of real estate developers. The valleys filled with houses and then with all of us — believers in the golden dream and disillusioned hustlers alike.

At the start of a new millennium in 2000, the dreamers still arrived. Not from “back east” but from the Global South and the Asian “far west.” Developers still turned square miles of farmland into tract house suburbia. Big, old-style corporations came and went. New technologies boomed and sometimes busted, but overall, the momentum in the systems of industry, finance and labor that defined California in the mid-20th century had slowed.

What California will be in its bicentennial year of 2050 is subject to unpredictable conditions. The nation becomes ungovernable; the San Andreas rips; drought worsens in the Colorado River watershed; AI-driven technologies deliver worst-case scenarios: social isolation, broken economies, accidental war.

Envisioning California’s Future

Absent these shocks, continuities will dominate California’s tomorrows. Demographic trends underway since 1990 will persist. Californians will be older, with a median age of nearly 42, up from a median age of 38 in 2025. Nearly one-quarter of us will be over 65, troubling the state’s image of youthful hedonism as well as the job market. Ethnic and political sorting will continue to send more Californians to red states and bring immigrants — in fewer numbers — to change the makeup of the political and civic organizations through which power is channeled. By 2050, nearly 50% of us will have Latino roots. The percentage of white non-Latinos will drift down to 25%. This realignment will likely bring a California-style Latino populism that disrupts conventional blue/red political binaries.

1950s California — young, better educated, risk-taking — excelled at turning Cold War defense spending into new industries and the shiny consumer products that defined a better tomorrow. When defense spending contracted in the 1990s, university researchers and hedge fund managers propelled newer and faster technological advances. The qualities that made California uniquely a leader in innovation are less obvious now, and the global competition is stiffer.

Forgotten are the cycles of drought that unmade the state’s cattle economy in the mid-19th century and drove titanic projects in the 20th century to bring water to places with little of their own. By 2050, we’ll use the water we have better through wastewater recycling, stormwater capture, limits on groundwater extraction, and agriculture fitted to a harsher climate regime.

But there will always be too little water in the southern half of the state. Fundamental ecological divides — north vs. south, coast vs. inland, temperate upland forest vs. dry chaparral lowland — will still fragment the California landscape and define Californians’ unique sense of place.

Sharp Differences in the Quality of Life

The costs of a California lifestyle — particularly the cost of housing — will widen the gap between households at the top and the low- and middle-income families below. Without new and creative housing programs, less than one-third of Californians will be able to finance a median-priced home in 2050.

Sharp differences in the quality of life between one community and another — begun by redlining neighborhoods in the 1930s — will persist. The conditions that predispose some Californians to become homeless aren’t likely to improve very much, although there may be fewer unsheltered people asleep on city streets.

Meanwhile, corporate refugees will follow the headquarters of Oracle, Northrop Grumman and Chevron out of the state, along with new technology billionaires and their enclaves of unimaginable privilege.

Will We Build the California We Deserve?

The challenge for Californians in 2050 will be one of imagination: to see themselves as inheritors of a compromised but still resourceful California.

Popular movements for equity and social justice are maturing. Political initiatives for health care, education, infrastructure renewal, homelessness and housing affordability could follow. The dark magic of AI is a threat to middle-income and low-wage earners, but it could become a platform to deepen our understanding of the environment and improve educational outcomes. A state with too many unaccountable boards, commissions and special districts and too many local governments jealous of their prerogatives could learn the hard lesson that a better future will come from regional coordination — in providing law enforcement, overseeing water management, responding to natural and human caused disasters and planning for economic development.

Californians need to accept the burdens of their history and shape their aspirations accordingly. They need to imagine a different kind of California, a California of shared potential, recognizing what had been lost or squandered in becoming Californian and understanding clearly what Californians can still achieve.

As hard as it will be to realize, the California we deserve is possible.

About the Author

D.J. Waldie is an essayist, memoirist, translator and editor. He previously served as a deputy city manager of Lakewood. His most recent book is “Elements of Los Angeles: Earth, Water, Air, Fire.”

This commentary was adapted from an essay produced for Zócalo Public Square.

This article was originally published on CalMatters and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.