FILE — Attendees participate in morning worship at the Faith and Freedom Coalition’s conference in Washington, June 22, 2024. Around 40 million Americans have left churches over the last few decades, and about 30 percent of the population identifies as nonreligious. (Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times)

- Roughly 40 million Americans left churches in recent decades, coinciding with rising unhappiness and loneliness.

- Secular alternatives like wellness trends and clubs often fail to replicate religion's sense of community and purpose.

- Despite declining affiliation, 92% of U.S. adults maintain some spiritual beliefs, suggesting a persistent human need.

Share

(Believing)

On Sundays, I used to stand in front of my Mormon congregation and declare that it all was true.

I’d climb the stairs to the pulpit and smooth my long skirt. I’d smile and share my “testimony,” as the church calls it. I’d say I knew God, Jesus Christ, the Holy Ghost, prayer, spirits and miracles were all real. I’d express gratitude for my family and for my ancestors who had left lives in Britain, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Norway to pull wagons across America and build a Zion on the plains. When I had finished, I’d bask in the affirmation of the congregation’s “Amen.”

In that small chapel by a freeway in Arkansas, I knew the potency of believing, really believing, that I had a certain place in the cosmos. That I was eternally loved. That life made sense. Or that it would, one day, for sure.

I had that, and I left it all.

I never really wanted to leave my faith. I wasn’t interested in exile — familial, cultural or spiritual. But my curiosity pulled me away from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and toward a secular university. There, I tried to be both religious and cool, believing but discerning. I didn’t see any incompatibility between those things. But America’s intense ideological polarity made me feel as if I had to pick.

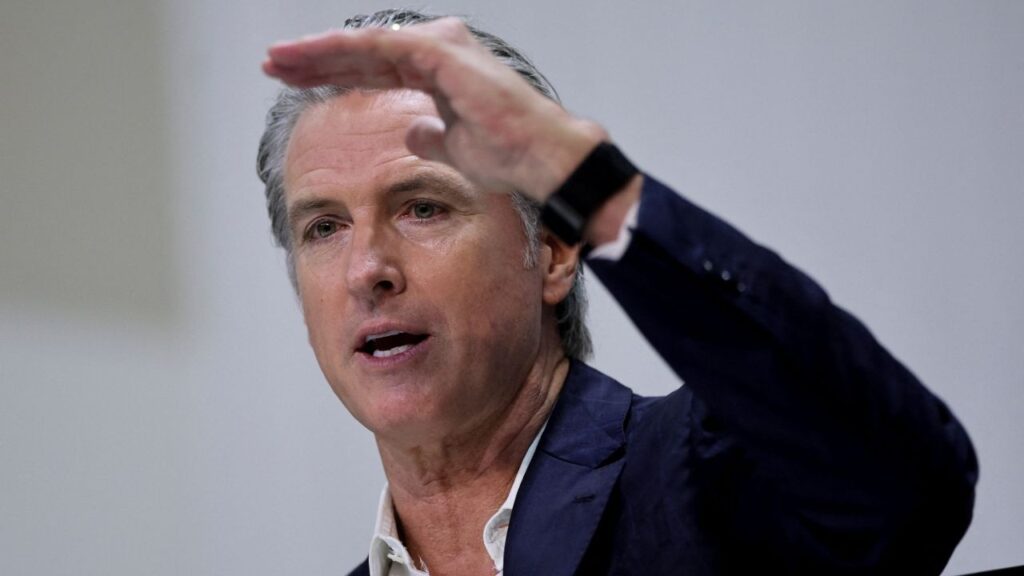

My story maps onto America’s relationship to religion over the past 30 years. I was born in the mid-1990s, the moment that researchers say the country began a mass exodus from Christianity. About 40 million Americans have left churches over the past few decades, and about 30% of the population now identifies as having no religion. People worked to build rich, fulfilling lives outside of faith.

That’s what I did, too. I spent my 20s worshipping at the altar of work and, in my free time, testing secular ideas for how to live well. I built a community. I volunteered. I cared for my nieces and nephews. I pursued wellness. I paid for workout classes on Sunday mornings, practiced mindfulness, went to therapy, visited saunas and subscribed to meditation apps. I tried book clubs and running clubs. I cobbled together moral instruction from books on philosophy and whatever happened to move me on Instagram. Nothing has felt quite like that chapel in Arkansas.

America’s secularization was an immense social transformation. Has it left us better off? People are unhappier than they’ve ever been, and the country is in an epidemic of loneliness. It’s not just secularism that’s to blame, but those without religious affiliation in particular rank lower on key metrics of well-being. They feel less connected to others, less spiritually at peace, and they experience less awe and gratitude regularly.

Now, the country seems to be revisiting the role of religion. Secularization is on pause in America, a study from Pew found this year. This is a major, generational shift. People are no longer leaving Christianity; other major religions are growing. Almost all Americans — 92% of adults, both inside and outside of religion — say they hold some form of spiritual belief, in a god, human souls or spirits, an afterlife or something “beyond the natural world.”

In Washington, religious conservatives are ascendant. President Donald Trump claims God saved him from a bullet so he could make America great again. The Supreme Court has the most pro-religion justices since at least the 1950s. Nearly half of Americans believe the United States should be a Christian nation. And singer Grimes recently said, “I think killing God was a mistake.”

The Rise of the ‘Nones’

I remember the first time I saw Richard Dawkins’ book “The God Delusion.” I was in middle school, at a Barnes & Noble in a strip mall down the street from my church. I stopped in front of the shelves, confronted with an astonishing possibility: It was an option not to believe.

Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist, intended to provoke. He was one of the patriarchs of New Atheism, a movement that began around the turn of the century. Disruptive forces — technological change, globalization and 9/11 — invited people to question both their relationship to faith and the role of religion in society. The New Atheists’ ideas helped make that interrogation permissible.

Religion was no longer sacrosanct, but potentially suspect. By 2021, about 30% of America identified as “nones” — people who have no religious affiliation.

But even as people left religion, mysticism persisted. More people began identifying as “spiritual but not religious.” In 2015, researchers at Harvard University began studying where these Americans were turning to express their spirituality. Reporters did, too. The answers included: yoga, CrossFit, SoulCycle, supper clubs and meditation.

“Secularization in the West was not about the segregation of belief from the world, but the promiscuous opening of belief to the world,” said Ethan H. Shagan, a historian of religion at the University of California, Berkeley.

Related Story: Trump Tells Prayer Breakfast He Wants to Root Out ‘Anti-Christian Bias’ and Urges ‘Bring God Back’

Happier, Healthier, More Fulfilled

Religion provides what sociologists call the “three B’s”: belief, belonging and behaviors. It offers beliefs that supply answers to the tough questions of life. It gives people a place they feel they belong, a community where they are known. And it tells them how to behave, or at least what tenets should guide their action. Religious institutions have spent millennia getting really good at offering these benefits to people.

“There is overwhelming empirical support for the value of being at a house of worship on a regular basis on all kinds of metrics — mental health, physical health, having more friends, being less lonely,” said Ryan Burge, a former pastor and a leading researcher on religious trends.

Pew’s findings corroborate that idea: Actively religious people tend to report they are happier than people who don’t practice religion. Religious Americans are healthier, too. They are significantly less likely to be depressed or to die by suicide, alcoholism, cancer, cardiovascular illness or other causes.

Answering Hard Questions

In a country where most people are pessimistic about the future and don’t trust the government, where hope is hard to come by, people are longing to believe in something. Religion can offer beliefs, belonging and behaviors all in one place; it can enchant life; most important, it tells people that their lives have a purpose.

People also want to belong to richer, more robust communities, ones that wrestle with hard questions about how to live. They’re looking to heady concepts — confession, atonement, forgiveness, grace and redemption — for answers.

Erin Germaine Mahoney, a 37-year-old in New York City, was an evangelical Christian for most of her life. She left her church in part because she disagreed with its views on women but said she has struggled to find something to fill the void. She wants a place to express her spirituality that aligns with her values.

She hesitated before saying, “I haven’t found satisfaction.”

“That scares me,” she added, “because I don’t want that to be true.”

Like Mahoney and many other “nones,” I, too, feel stuck. I miss what I had. In leaving the church, I lost access to a community that cut across age and class. I lost opportunities to support that community in ways that are inconvenient and extraordinary. I lost answers about planets, galaxies, eternity.

But I don’t feel I can go back. My life has changed: I enjoy the small vices (tea, wine, buying flowers on the Sabbath) that were once off-limits to me. Most important, though, my beliefs have changed. I’ve been steeped in secularism for a decade, and I can no longer access the propulsive, uncritical belief I once felt. I also see too clearly the constraints and even dangers of religion. I have written about Latter-day Saints who were excommunicated for criticizing sexual abuse, about the struggles faced by gay people who want to stay in the church.

I recognize, though, that my spiritual longing persists — and it hasn’t been sated by secularism. I want a god. I live an ocean away from that small Arkansas chapel, but I still remember the bliss of finding the sublime in the mundane. I still want it all to be true: miracles, souls, some sort of cosmic alchemy that makes sense of the chaos.

For years, I haven’t been able to say that publicly. But it feels like something is changing. That maybe the culture is shifting. That maybe we’re starting to recognize that it’s possible to be both believing and discerning after all.

—

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Lauren Jackson/Haiyun Jiang

c. 2025 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Steam Down for Thousands Tuesday, Downdetector Shows

Mexico Imposes 156% Tariff on Sugar Imports