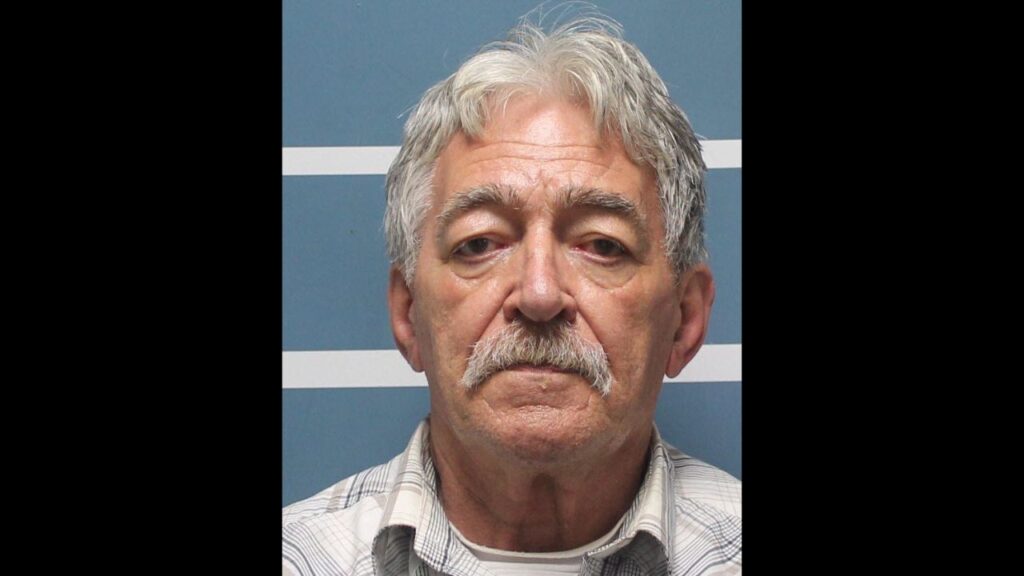

Michael Swanson, chief agricultural economist, with Wells Fargo, gave the introductory speech at the 43rd Fresno State Agribusiness Conference Wednesday, Nov. 15, 2024. (GV Wire/Jahziel Tello)

- Fresno State hosted its 43rd annual Agribusiness Management Conference.

- Panelists said an overexuberance of investment in nuts, especially, expanded the industry to unsustainable levels.

- Regulatory effects of water and energy laws have cut in growers' bottom lines.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Fresno State on Wednesday brought together economists, lenders, farmers, and industry representatives to discuss the changing landscape in California agriculture for its 43rd annual Agribusiness Management Conference.

Saying agriculture is in the midst of a drastic transition, panelists struggled to paint an optimistic picture of ag’s future. But the event’s economist assured growers, saying Americans will only want more food.

But farmers will have to overcome the after effects of an overexuberance of investment and expansion and find a price point that can pay for increasing regulations and water costs while also staying competition with rising foreign markets.

Easy Money Lead to Overexuberance: Covington

The talk comes amidst notable bankruptcies in the ag world, collapsing commodity prices, land sell offs, and high interest rates.

The industry got into trouble after years of cheap money and low interest rates, said Curt Covington, senior director of institution credit with AgAmerica Lending.

“When money’s free, it invited a lot of private equity into the space here in California, plus we had a number of farmers who had deep pockets with a lot of cash that saw undeniable exuberance around the nut business,” Covington said.

Almond prices, once exceeding $4 a pound, collapsed in a short amount of time, falling to around $1.50 in some cases, according to industry experts.

Related Story: Ag Recession? Years of Plenty May Be Over, but Reality Isn’t as Bleak as ...

Of the 1.4 million acres of almonds in the state, 150,000 is expected to be pulled out from 2023 to 2024.

While some blame can fall on farmers and investors, Covington said lenders were not as scrutinizing as they should have been.

Even with California’s landmark water law, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act being passed in 2014, farmers chased high margins with little restrictions on water, said Casey Creamer, president of California Citrus Mutual.

With water restrictions starting to trickle down, farmers, investors, and lenders are already reacting, despite SGMA’s full effect not yet being fully realized.

“The next decade or so is really going to be a sort of reevaluation of all the assets that are on the ground relating to water,” Creamer said.

Kern County the ‘Poster Child’ of SGMA: Ming

Land values have already collapsed in regions with poor allocations, said Mike Ming, land appraiser and president of American Society of Farm Managers & Rural Appraisers.

Kern County ag may suffer the most. Land valued at $15,000 an acre has fallen to less than $4,000 in areas outside of water districts. The amount of water that can be safely pulled out of the ground — a third-of-an-acre-foot — might reduce a 1,000-acre orchard to only 80 viable acres for the nut that needs upwards of four acre-feet of water a year.

“We’re going to go into probation by February. (Department of Water Resources) is going to put us in probation, there’s too much infighting,” Ming said.

West of Interstate 5, brackish aquifers prevent any groundwater pumping. Farmers there rely on the state’s water delivery system, which will be drastically cut back.

Ming estimated a loss of 257,000 acres of irrigated farmland out of 830,000 acres.

Even so-called “vulture” capital — investment funds looking for cheap deals — have been hesitant to pull the trigger, Ming said.

Some positive notes? Creamer talked about citrus’ continued stability. After suffering the effects of then-President Donald Trump’s tariffs during his first term, the industry established itself better in domestic markets, which could help it weather a new spate of tariffs should Trump enact new tariffs.

Covington said the newest investor trend has been “patient capital” coming from high net-worth individuals looking to spend $5 million to $10 million on a farming operation — just the amount aging farmers getting out of the business have to sell.

Don’t Try to Predict a Recession: Swanson

Talk of recession has circulated the ag world, but Michael Swanson, chief agricultural economist, said while economists have predicted 37 since 1998, only three have happened in that time.

“Recessions do matter, but they don’t happen very often,” Swanson said. “Think about that, we name recessions just like we name hurricanes.”

Even in recessions, food spending is the most stable, he said.

But, with the biggest population in history, the highest wages ever, and the highest employment ever, food spending should be strong. Even during the employment collapse of the Great Recession, food spending never went down, he said.

The trick will be figuring out what price to sell commodities. What California agriculture has going for it, he said, is the quality factor. American consumers, who are willing to spend money for premium products, may be the best market for ag.

But he said the market will have to find a balance.

The 34% returns in 2010 were too good to last while the 19% returns in 2023 were too bad to last.

“It’s the nature of the California system to go down and stay down,” Swanson said. “Now will it happen in 2025 like magic? No. It might be a multiyear period.”

In a follow up question, though, Swanson doubted the ability to recoup costs put upon farmers by SGMA.

Regulations Written Quickly and Figured Out Later: Brown

As the industry faces higher cost of money, low commodity prices, and diminished land values to borrow against, regulatory costs add to farmers’ woes, panelists said.

Farmers often have to buy new equipment to keep up with water and energy regulations. And while grants help offset costs, eligibility requirements are often outdated, said John Chandler, owner of Chandler Farms.

A grant program would have helped pay for solar panels to power a pump on Chandler’s farm, he said. But to qualify, he had to hire an archeologist to conduct a cultural analysis of the land where the solar panels were supposed to go. The cost for compliance nearly exceeded the money it would bring in.

Many farmers don’t oppose adapting technology if it helps the bottom line, said Laura Brown, head of the environmental department at J.G. Boswell Company. But laws such as the electrification of farm equipment aren’t realistic with California’s power grid limitations.

And so much regulation comes from agencies rather than elected officials, Brown said. And the rules aren’t figured out until after they’re implemented. That leaves farmers forced to comply with rules in a world of uncertainty.

“The policy is being passed and then retroactively is when they’re allowing the conversations with stakeholders to really have a meaningful opportunity for change,” Brown said.

Soares Wants Students to Engage With Lawmakers, Community

Keynote speaker George Soares, attorney, farmer, and advocate, said while ag is always shifting, he’s never seen it like it is now. Regulators in California have left what farmers need out of the equation, he said.

When SGMA was being written, Soares met with then-Gov. Jerry Brown about the proposal. He said while farmers recognize the need to save aquifers, they need adequate surface water supplies.

He told students about the importance of connecting with their audience to make meaningful change. Rather than speaking in terms unrecognizable to those outside the industry, he said agricultural advocates should speak about the industry’s impact.

Citing the Public Policy Institute of California’s estimation of 1 million acres of ag land lost in the Central Valley, he said it made him think of the 1930s dust bowl.

“I’d like us farmers to be talking about community a lot more than we do,” Soares said.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories