An outbreak of highly pathogenic avian flu at Central Valley dairies has farmers struggling to keep up with infections. (GV Wire Composite/David Rodriguez)

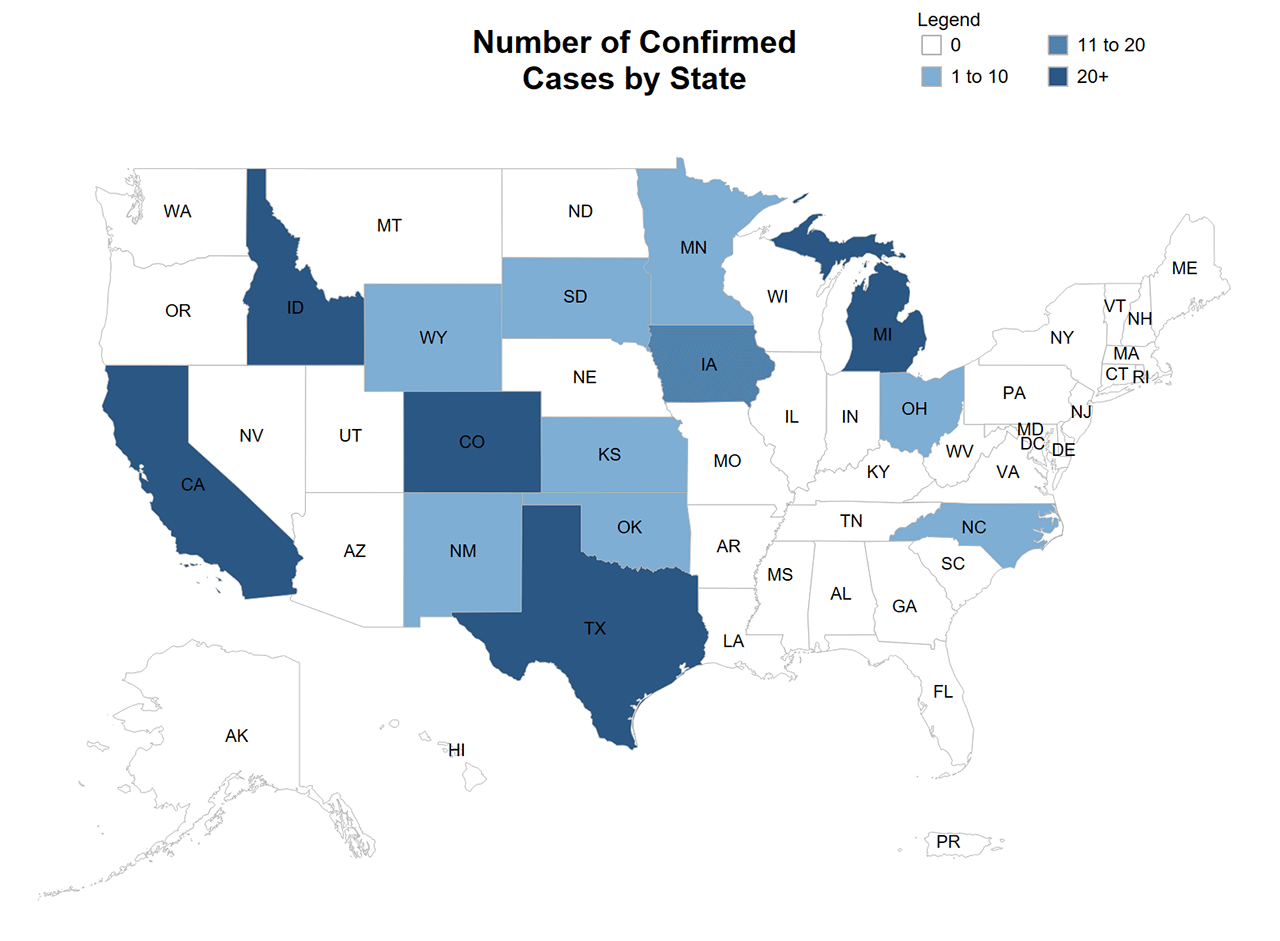

- The highly pathogenic avian flu may have infected more than 100 dairies in the Central San Joaquin Valley, reports show.

- Some herds have hundreds of cows infected, requiring them to be isolated, hydrated, and fed.

- In addition to cow health, an industry leader fears what the disease will mean for dairies already beset by higher operating costs.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Landon Fernandes has heard the number of Central Valley dairies with cows infected with highly pathogenic avian flu may have surpassed 100. His own dairy got hit by the disease and he’s working full time to keep his cows hydrated, fed, and healthy.

“The first day on your farm you might see a handful of sick cows,” said Fernandes, a Tulare County dairyman. “The next day it’s maybe a dozen or two dozen sick cows. There’s a ramp-up period until about day seven to 10 where you reach your peak. I’ve talked to some dairy farmers that have had up to a third of their herd infected. That’s when you’re treating hundreds if not thousands of cows a day.”

The avian flu has fully hit the Central San Joaquin Valley and is moving north, said Anja Raudabaugh, CEO of Western United Dairies. Any dairies not being observed or under quarantine orders are taking exhaustive precautionary measures.

Farmers are finding more out about the disease’s effects on their cows daily. Researchers are narrowing down how the virus travels and implementing protocols for farmers. However, these containment measures — coupled with long-term effects on the cows themselves — have an industry already beset by rising costs and low returns teetering.

“All those ramifications are absolutely going to be crippling to some dairies,” Raudabaugh said. “If a dairy was in a financially tough position before this and they get hit with this, I don’t see them coming through this.”

Keeping Cows Hydrated Is Key

Within hours of infection, cows stop digesting their food, they stop eating, and they stop hydrating, said Raudabaugh. Cows develop very high fevers.

“Those things happen in a matter of hours,” Raudabaugh said.

Related Story: FDIC’s Proposed Changes Would Undermine Farms, Businesses, and Nation’s ...

Nose-to-nose contact between the animals spreads the disease, so once the disease is detected, animals need to be isolated. Last week’s heat wave put extra pressure on the animals, forcing dairies to keep barns cooler.

For cows with milder symptoms, treatment might only take a day or two, Fernandes said. Aspirin, Vitamin B, fluids, and food can usually be enough to get a cow to recovery. Cows with worse symptoms need to be “drenched” which means putting a tube down their throat to ensure they’re getting enough fluids.

“Other cows that have been more affected and a lot more ill from the virus, we’ve been administering fluids via drenching, drenching cows with electrolytes, getting dehydrated cows adequate fluids to help combat the virus,” Fernandes said.

Milk Production Recovery Rates Split

Avian flu is deadly in poultry, devastating farm and wild birds throughout the country. Fatality in cows is far less pronounced, especially with treatment.

Virologists think the jump to cows can be traced back to a wild bird at a Michigan poultry farm, Raudabaugh said.

A worker’s split shift between the poultry farm and a dairy brought it to cows. There, it adapted to mammary tissue, Raudabaugh said.

“It only cleaves to mammary tissue, which is why beef is not affected,” Raudabaugh said. “This is very, very interesting because we’ve not seen that development before.”

Researchers are starting to get January and December data back from eastern states that had the disease first.

Related Story: How California’s Prized Solution for Methane Gas Is Backfiring on Farmers

Fernandes has seen most of his cows starting to recover and produce milk again, but that’s not universal.

Many dairies are finding long term milk production not returning, Raudabaugh said. For some farmers, that’s meant culling.

But with beef and milk prices so high, replacement heifers are scarce. And as the virus continues to affect more dairies, finding healthy cows becomes even harder.

“I can tell that there are going to be some cows that don’t come out of it, but it’s too soon to put a figure or a percentage or any sort of statistic to that yet,” Fernandes said.

(Editor’s Note: The latest Food and Drug Administration updates on the avian flu are at this link.)

Tougher Biosecurity Measures in Place

Pasteurization kills the virus and cows with the disease are taken off the line, so dairies are still producing milk. But they do so with “demonstrably” increased biosecurity measures, Raudabaugh said.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture put strict quarantines on dairies with detected viruses. That means continued testing and containment measures, she said. Dairies have regular daily shipments, but with uncertainty around how the disease spreads, extra caution is being taken.

Deliveries to dairies might be a mile up the road, she said. Any trucks going into a facility need to be hosed down with a bleach solution. Workers have been given protective gear such as gloves, goggles, and face shields to keep them safe. The disease can be aerosolized through the milking process, so workers need extra protection. The cow-to-human transmission level has been limited.

Symptoms in humans turn out to be similar to conjunctivitis, Raudabaugh said, so it’s possible not all cases are being reported.

But in addition to containment measures, multiple state and federal agencies need dairies to report their results.

Involved agencies include California Department of Agriculture, USDA, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Fish and Wildlife, and more.

“It’s very stressful because at the same time you’re trying to take care of your animals who are on death’s door,” she said.

Containment Costs Come as Farmers Expect Minimal Returns

When the disease first began showing up, experts thought wild birds brought the pathogen from dairy to dairy. Birds like to hang around dairies for the bugs, Raudabaugh said. But researchers have ruled out that the disease is spreading that way.

Finding that out has been a relief, but other methods of transmission need to be ruled out.

What’s called fomite transmission — objects such as boots, gloves, or tires — is now being considered.

But that could mean tires, boots, or even flies.

Raudabaugh said they are trying to keep quiet exactly which dairies are under quarantine because animal rights activists have been seen monitoring animals. Researchers worry activists could also become vectors.

The extra costs come with drastically lowered milk production rates. Government checks to help with additional containment costs help, but most California dairies are too big to qualify for USDA programs.

“That’s a huge problem because in about two weeks, these farms under quarantine are going to start to get their milk checks for September,” Raudabaugh said. “And those milk checks are probably going to be half of what they were the month before.”