Legislators put one of the most consequential housing laws into a budget bill where Assemblymember David Tangipa, R-Clovis, said they didn't get a chance to discuss its merits. (GV Wire Composite)

- Legislators hid one of the most consequential California housing bills in recent years inside of a budget bill.

- One portion of AB 130 creates a fund paid by taxes on new development to go toward affordable homes.

- Rising costs of single-family homes are driving people farther away from work, experts say, defeating the purpose of the VMT law.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Lawmakers had only a few days to review one of California’s most consequential housing bills in recent years.

And, with almost no deliberation, lawmakers approved Assembly Bill 130 despite the fact that housing advocates and environmental attorneys say two important sections of the law could greatly increase the cost of new homes.

When Assemblymember Jesse Gabriel, D-Encino, introduced the bill in January, it came before lawmakers nearly completely blank — a common practice in California politics, said Assemblymember David Tangipa, R-Clovis.

Requests for comment from Gabriel’s office were not returned.

“Instead of actually doing the full deliberation process on starting it from the very beginning, having some clear intentions, debating on the budget, we will wait all the way until the very end,” Tangipa said.

By June, the bill turned into a lengthy, complex bill changing California’s environmental laws days before lawmakers had to approve a budget. One part largely praised by builders included a change in the California Environmental Quality Act, which Gov. Gavin Newsom told lawmakers had to be in there or he would veto the budget, according to multiple sources, including Tangipa.

“I thank the many housing, labor, and environmental leaders who heeded my call and came together around a common goal — to build more housing, faster and create stronger affordable pathways for every Californian,” Newsom said in a statement.

More Drivers, Longer Commutes, More Expensive Homes: Dunmoyer

However, as one portion of the law reformed CEQA, another strengthened the law cited in countless lawsuits over the decades, said Dan Dunmoyer, president and CEO of the California Building Industry Association.

AB 130 creates a statewide bank into which builders pay extra taxes for projects that can’t get the number of travel miles down to an acceptable level. The cost is ultimately paid for by buyers of new homes, and the money goes to affordable housing projects across the state.

Dunmoyer called the original VMT law an “abject failure” as housing costs have doubled while commutes have gotten longer and the number of drivers in the state have increased since the 2013 law was approved. AB 130 could mean even more fees as California lawmakers turn to new construction to pay for the high costs of affordable housing.

“The old theory’s cost us billions of dollars and hasn’t worked and has really hurt housing,” Dunmoyer said. “So now, the new theory is ‘we’ll use housing that’s not downtown to subsidize affordable housing that is downtown.’ ”

Legislators Vote on Blank Bill

Lawmakers Don’t Get Answers, Governor Gets to Decide: Tangipa

Lawmakers gave the governor’s Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation until July 2026 to figure out the rules around the bank. Some attorneys and developers say rather than an option, it could be the norm, adding thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars to the cost of new businesses and homes.

Analyses show that in some areas of California, that amount could be $315,000 a home.

While Tangipa supported the portion of the bill creating CEQA reform, he said without clarity on the affordable housing bank, he couldn’t support it. He abstained from voting on the item.

“None of it makes sense to me. What is the intended use of the VMT bank? Groups are going to be paid out of it — that is one of the questions that I wish I had more time to ask,” Tangipa said. “But when we move the process the way that we do in Sacramento, we don’t have proper deliberation to deep dive into the details. And especially when sometimes they give me this type of legislation 24 hours before it comes onto a vote.”

Dunmoyer said the building association was originally neutral on the proposal. Created by Assemblymember Buffy Wicks, D-Oakland, the plan gave builders the option to pay into affordable housing as a way to lower VMT fees. Between then and AB 130, it became mandatory, Dunmoyer said.

Being a statewide fund, the bill could take money away from one region and put it toward another, Dunmoyer said. It could also be another source of revenue for lawmakers to tap into during a budget deficit.

“Let’s say you’re building in Fresno, the Central Valley. The statewide bank, you pay into this fund, they can allocate it to Sacramento or L.A. You’re supposed to try to put it in the region, but it’s not a requirement,” Dunmoyer said. “And God forbid, we actually have a budget deficit — which we do — and someone decides, ‘hey, let’s just raid the fund this year because we need to take care of important things like health care for citizens or noncitizens, whatever the issue may be.’ ”

Enough Cash Will Get a Project Approved: Mirante

Before AB 130, the law allowed local governments to exempt projects from vehicle miles traveled assessments if legislators could deem them important enough and the mitigation costs too high, said Louis Mirante, senior vice president of public policy and housing with the Bay Area Council.

“That was a very popular route for housing projects, especially sprawl or at the fringe of community, big tract home projects that would be very typical in the Central Valley,” Mirante told GV Wire.

AB 130 could be used as a way to get rid of that caveat, resulting in new developments or shopping centers being charged millions of dollar to open.

“Now with this VMT mitigation bank there is something that you could theoretically just dump cash into until you hit the right amount of cash and your VMT is fully mitigated,” Mirante said. “That would be extremely expensive for a lot of projects.”

Housing Policies Driving Out Families, Middle Class: London

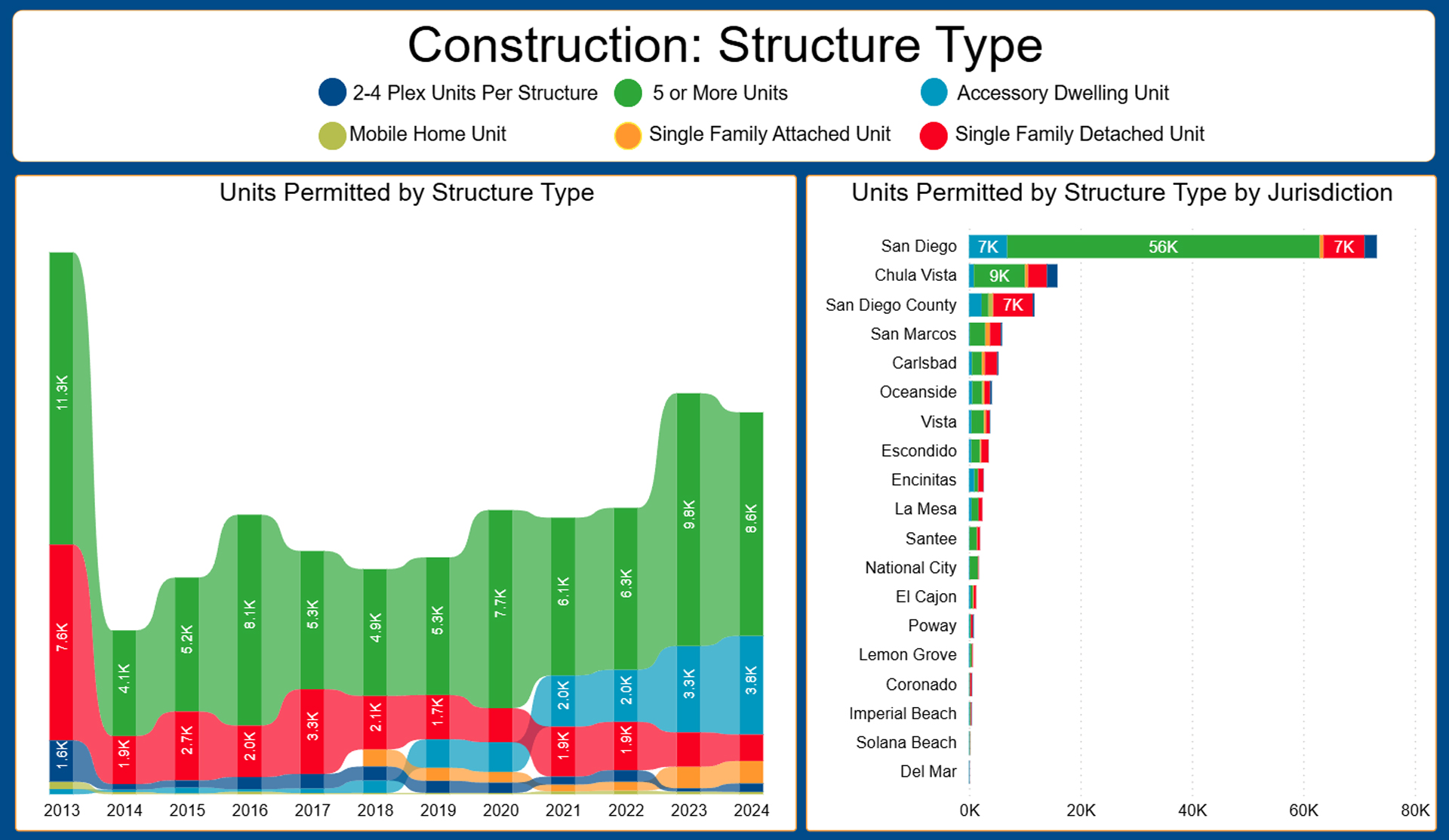

The state’s reliance on infill development for housing minimums will squeeze future generations, said Gary London, senior principal with London Moeder Advisors, a San Diego real estate consultancy.

“The state basically interpreted affirmative housing policy to be focused on infill — areas near transit, near already existing communities — which is fine, but that’s exclusively what they focused on,” London said. “They basically ignored the need for development of subdivisions and master plan communities.”

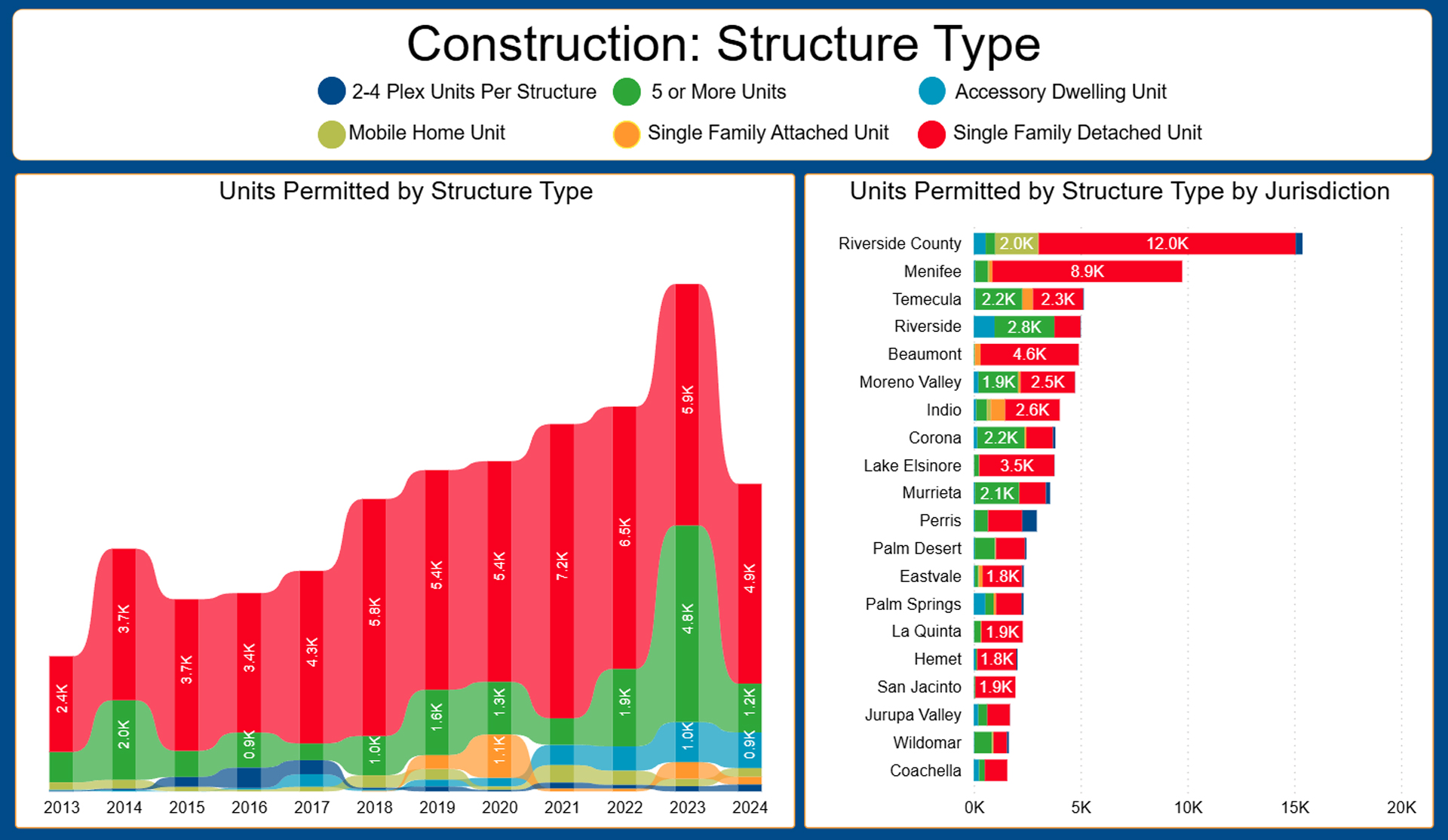

The lack of single family homes — in large part due to existing VMT laws and housing policy — has pushed San Diego residents out to Riverside County where they drive hours to get to work, London said.

Census data shows a majority of the 47,000 daily trips on the I-15 from Riverside to San Diego are for work.

San Diego’s association of governments, SANDAG, is now trying to reduce that usage with a bus route from Temecula to San Marcos. More immediate consequences of housing policy may be increasing travel miles, but London said it will have longer term consequences as well.

Similar to Fresno’s relationship with Madera developments Riverstone and Tesoro Viejo, London said families have moved to nearby Riverside County.

Families still want single-family homes, but increased cost of living, driven by housing costs, has driven people elsewhere, London said. San Diego has met its state requirements for above moderate income housing, but the majority is small studios and one bedrooms, he added.

Population growth in San Diego County slowed to less than 1% over five years while Riverside County exceeded 3.2%. Births kept population counts flat, countered by an average net outmigration of 13,679 people a year, according to London Moeder Analysts.

“If you really want to negatively impact an economy, as good a way to do it as any is to make your housing and your overall cost of living more expensive,” London said.

New Homes Have Become the State’s Tax Collector: Dunmoyer

AB 130 generates money for affordable housing without the appearance of raising taxes, Dunmoyer said.

“We have chosen — unlike any other state, red or blue — to use the new home as the hidden tax collector,” Dunmoyer said.

Most fees go toward building new parks, schools, water and sewer access, but AB 130’s fees won’t go to help the payer. California’s policy often contradicts itself.

By 2035, lawmakers want all vehicles to be zero emission.

Before VMT, California taxed new homes to expand roads or build new street lights to lower road congestion, called a “level-of-service.” Those fees still exist under different names but now contradict the state’s goal to reduce driving miles and get people out of their cars, Dunmoyer said.

“If you want to watch a builder’s head explode, it’s when they have to pay to expand the roads and pay to reduce the use of the roads simultaneously,” Dunmoyer said. “We are so schizophrenic on this issue that you’re paying basically to contradict yourself.”

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Renee Good’s Relatives Speak to Lawmakers in Washington