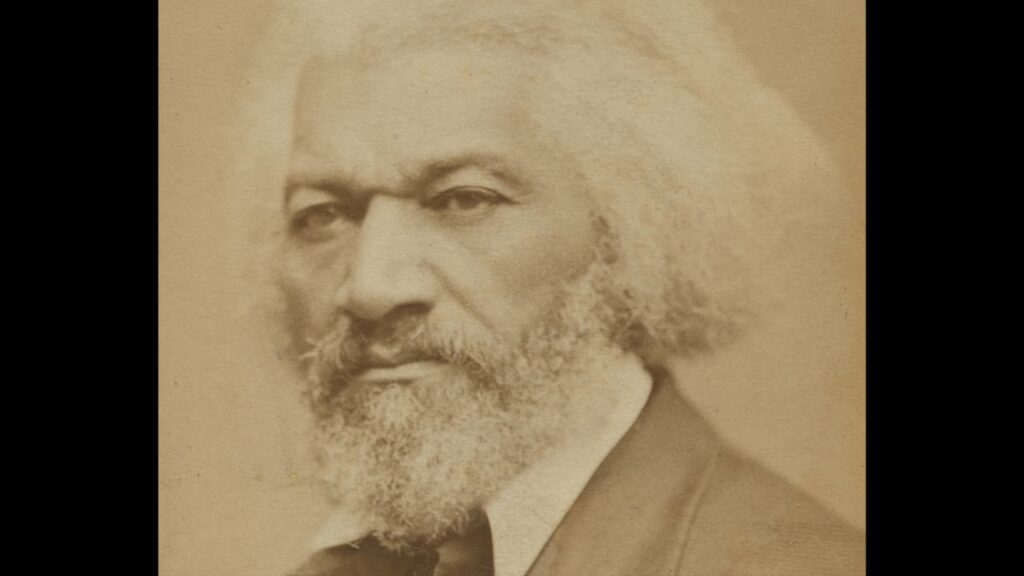

Haley Matlock, left, Ryan Matlock's sister, and Christine Dougherty, Ryan's mother, hold a photo of Ryan at their home in Yucaipa on June 12, 2024. (CalMatters/Jules Hotz)

- After a lawmaker asked Christine Matlock Dougherty to testify on behalf of bills to regulate mental health insurance, the legislation didn't pass.

- CalMatters had described her son’s passing due to a fentanyl overdose in a special report on mental health insurance denials.

- Supporters of Assembly Bill 669 have several theories about the reasons for its demise.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

Christine Matlock Dougherty received the text just after noon on the last Friday in August.

The mental health legislation she’d been advocating for in memory of her son was dead, held indefinitely by the state Senate Appropriations Committee in an annual culling of bills.

Just like that.

Poof.

In the text, Sherry Daley, a lobbyist with the California Consortium of Addiction Programs and Professionals, which sponsored the bill, explained simply:

“The bill was held. It won’t be moving forward this year. Sorry.”

More than four years have passed since Dougherty lost her 23-year-old son, Ryan Matlock, to a fentanyl overdose after his insurance refused to cover his stay in residential treatment.

The office of Matt Haney, a Democratic state Assemblymember from San Francisco, had reached out to her after CalMatters described her son’s passing in a special report on mental health insurance denials. The lawmaker asked her to testify on behalf of the bill to help prevent similar tragedies.

She initially hesitated.

Talking about what happened to Ryan was already so painful. And to a room full of strangers in suits? With a video recording going?

Insurance Refused to Cover After Three Days in Care

But Haney’s office explained that Assembly Bill 669 would prevent health plans from reviewing a patient’s eligibility to stay in substance use treatment for the first 28 days after an in-network provider first approved the treatment. Ryan’s health plan had declined to cover his stay at the treatment facility after just three days.

Dougherty knew what her son would want her to do.

In recent months, Dougherty made three trips up to the state Capitol to testify on behalf of Haney’s proposal and another insurance-related bill that would require health plans to report data about how often they deny treatment.

On those visits, she breathed deep, dabbed her eyes, told her story.

If talking about what happened to Ryan could change the law, it seemed worth it.

But what if the law didn’t change?

Insurers Oppose Bill

Insurers lobbied against it. The California Association of Health Plans, which opposed the bill, said via email that it could have led to patients remaining in treatment longer than necessary, and could have created openings for bad actors in a residential treatment industry they said was already beset with “widespread waste, fraud and abuse”.

Haney’s bill wasn’t the only one held by the Senate Appropriations Committee that Friday. The committee is the last check before a bill can go to a final Senate vote. It sometimes holds bills without explanation.

Of 425 bills that came before the committee, 309 were sent along to the Senate floor.

A representative of state Sen. Anna Caballero, the committee’s chairperson, did not immediately respond to an email and phone call requesting comment Monday. But the bill’s supporters have their own theories about the reasons for its demise.

Among them:

The state is in an extremely tough financial year, with revenue streams down and federal funding at risk. The Department of Managed Health Care’s estimate that the bill would cost more than $2 million a year — an amount Haney calls “less than budget dust” — certainly didn’t help its chances.

The health insurance lobby opposed the bill and the state agency that regulates most health plans didn’t offer its help. A spokesperson for the Department of Managed Health Care said it didn’t take a position on the bill.

Or, perhaps, the bill’s proponents say, they just ran out of time.

Bill’s Demise Is ‘Devastating’

Haney called the bill’s loss “devastating.” He dismissed cost as a nonsensical “completely backward” reason for killing the bill.

“When we don’t invest in treatment and we don’t get people off of drugs, there are astronomical costs to our state at every single level,” he said. “And so this is about investing in prevention, but it’s also simply holding private insurers accountable to Californians who should get the care they’re paying for.”

He pointed to what he described as a pattern of bills being killed in the Legislature, ones that hold private health insurers to account.

“That’s a pattern that Californians should be deeply angry about,” he said.

Families like Ryan’s “have the courage to share their story and it’s painful and it’s traumatizing and they put hope that we will hear them,” he said. “And in this case the Legislature did not and so we have to move forward and we have to try again.”

Dougherty, for her part, had originally assumed the entire Legislature would have the chance to weigh in on the proposal before it was discarded, not just a small cadre of senators.

She felt frustrated. But also proud.

She had done her best to help make the experiences of families like her own a little more human for policymakers, a little less lost in talk of statistics and probabilities.

She remains prepared to keep telling her story.

“I will do it again,” she said. “For Ryan.”

This article was originally published on CalMatters and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Is ChatGPT Down Again? Here Is What We Know

Chloe Kim, Once a Teenage Phenom, Loses to a New One