California's kids are trailing behind, with a new report placing them in the bottom third for overall well-being among all states. (EdSource/Betty Márquez Rosales)

- The state’s best ranking was in children’s health; worst was in economic conditions.

- Chronic absenteeism in California rose from 12.1% in 2018-19 to 30% in 2021-22.

- Racial inequities play a significant role in the state's child well-being index measures.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

California’s children rank in the bottom third of all states in overall well-being, according to a new report released this week.

Betty Márquez Rosales

EdSource

The authors of the report, “2024 KIDS COUNT Data Book: State Trends in Child Well-Being,” found that over half of California’s 3- and 4-year-olds are not in school, less than one-fourth of its eighth graders are proficient in math, and a greater number children and teens per 100,000 died than in previous years.

“One way to think about it is where we see the most progress are the states who are investing in their children — heavily in their children,” said Leslie Boissiere, vice president of external affairs at the Annie E. Casey Foundation, who oversaw the compilation of the report.

(This article originally appeared on EdSource.)

Now in its 35th year and published by the foundation, a private philanthropy and research organization, the annual report measures children’s well-being across 16 indicators within the categories of education, economic well-being, health, and family and community.

Out of all states, California ranked 43rd in economic well-being, 35th in education, 10th in health, and 37th in family and community.

Related Story: What Happens When California Schools Call for the Police?

California’s children fared better than most other states only in the health indicator. Even so, the number of babies with low birth-weight slightly increased from 7.1% in 2019 to 7.4% in 2022, as did the number of child and teen deaths, rising from 18 per 100,000 in 2019 to 22 per 100,000 in 2022.

“The movement in indicators generally follows investments, and it depends on the particular state of how they’re investing in their children,” Boissiere said.

This year’s report largely focused on comparisons between 2019 and 2022 data to provide a pre-pandemic and post-pandemic view of how children are faring, Boissiere said. Sources for the data included the U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Education, the National Center for Education Statistics, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Impact of Low Well-Being on Chronic Absenteeism

The authors noted that the report’s findings provide context to the conversation on chronic absenteeism, which is defined as missing 10% or more of the school year.

The percentage of chronically absent students in California skyrocketed from the pre-pandemic rate of 12.1% in the 2018-19 school year to 30% in 2021-22. The reasons for such high absenteeism vary from district to district and even from student to student, but experts agree that the issue is exacerbated when children’s basic needs are not being met.

“What we know is that it’s critically important that all children arrive in the classroom ready to learn and, in order for them to be ready to learn, their basic needs have to be met,” Boissiere said.

National data included in the report highlighted the relationship between absences and academic performance. The more students miss school, the lower their reading proficiency.

Related Story: English Learner Advocates in California Oppose ‘Science of Reading’ Bill

In 2022, the percentage of fourth-grade students nationwide scoring proficient at reading was 40% for students with zero absences in the month before they took the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP. Reading proficiency lowered to 34% with one to two absent days in that month; to 28% with three to four absences; 25% with five to 10 absences, and down to 14% for students who had more than 10 absences in the same one-month time frame prior to taking the NAEP.

The authors also found that racial inequities play a critical role in nearly all the index measures in the report.

“As a result of generations-long inequities and discriminatory policies and practices that persist, children of color face high hurdles to success on many indicators,” the authors wrote.

For example, the authors found “alarming increases” in the rate of child and teen death rates among Black children nationally, and that American Indian or Alaska Native children “were more than twice as likely to lack health insurance.”

Disaggregating racial demographic data also pointed to notable inequities.

For example, authors found that Asian and Pacific Islander children experienced one of the lowest rates of poverty nationally at 11%; the rate of poverty among Burmese children was 29%, 24% for Mongolian children, and 23% for Thai children. The national average for child poverty is 16%, per the report, highlighting the stark poverty rates for many Asian children nationwide.

Related Story: Most California High School Seniors Shut Out of Even Applying to the State’s ...

Looking at distinct racial inequities, the authors found exceptions where children of color were faring better than the national average. For example, Black children were more likely to be in school at ages 3 and 4, to be insured, and to have a head of household with at least a high school diploma. Latino children and teens had lower death rates, and they were also less likely to have low birth-weight.

“Today, kids of color represent a majority of the children in the country, as well as in 14 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands,” the authors wrote. “The future success of our nation depends on our ability to ensure all children have the chance to be successful.”

About the Author

Betty Márquez Rosales is a reporter for EdSource. She covers education in California, with a focus on early learning and the achievement gap. She previously worked as a reporter for The Press-Enterprise in Riverside, where she covered higher education and local government. She holds a bachelor’s degree in English and a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Southern California.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

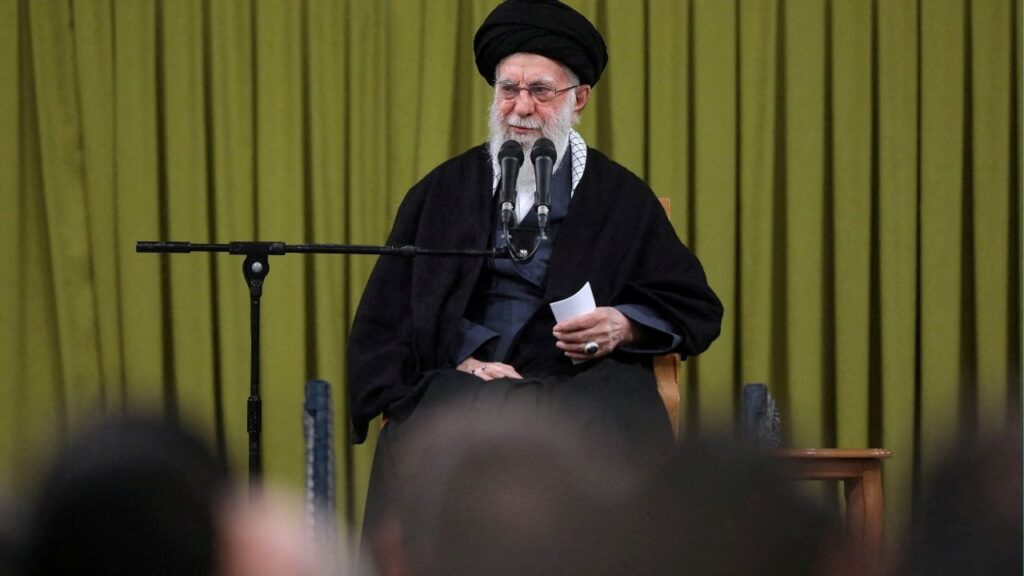

Who Could Take Over for Ayatollah Ali Khamenei?

Why Have You Started This War, Mr. President?