Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Adam Craig Hill left Rockaway, New Jersey, to become a famous writer in California. He wound up a polarizing and infamously fallible county supervisor in San Luis Obispo. Through it all, Hill’s big personality and addiction to shortcuts put him on an unpaved road to the Dead Poets Society.

Donnell Alexander

At his Shell Beach home two Augusts ago, the Fresno State English Department product took his own life — months after winning election to a fourth term. SLO is a place that Oprah once called “the Happiest Place on Earth.” Yet, in that season of COVID-induced isolation and with the FBI bearing down on him and twisting his mind, suicide began to make a kind of sense.

The money he pocketed from a local cannabis entrepreneur named Helios “Bobby” Dayspring — $32,000, according to the feds — might not even cover parking for a bonafide San Francisco legal weed crime. In a New York deal? The Dayspring money might not get you to the table. But the demise of Adam Hill happened in an American pocket that only Central California residents and tourists are checking for, and the bribe he took to shape county cannabis law meant immense trouble for this little paradise.

I worked with Adam at a critical juncture in our young adulthoods. He was a grad school poet trying to break into prose, and I was the top editor at Fresno State’s Daily Collegian. Hill signed his weekly column copy “adam craig hill,” a lower-case bit of posturing that caused my eyes to roll.

We quietly went at it, over style, and I fired him mid-semester.

Caught in the FBI’s Snare

Hill hadn’t crossed my mind much beyond a passing glance on LinkedIn — until 2018, when word got out that the FBI would start examining corruption within the state’s emerging cannabis industry. Since my decades-ago stint at The Collegian I’d gone on to tell many kinds of stories, and in the year of this start-up federal investigation I’d begun to report and write the WeedWeek California newsletter. Whispers about shady weed commerce in Sacramento emerged. South of my L.A. crib, there were bribery issues in Adelanto, for sure. And — for reasons long forgotten —that gorgeous Central Coast vacation realm felt suspect.

Two years later, the progressive politician would be dead, San Luis Obispo County’s biggest weed dealer nailed by the feds for bribery, and SLO political culture rocked by conspiracy allegations. A locally popular indie-news site with deep sources and an intense following — which you’ll hear more about later — has placed the number of SLOcals interviewed by the FBI at more than 40.

More than two dozen sources talked to me for this profile, many requesting not to be quoted by name. Among those declining to be interviewed at all were some of Hill’s closest political, professional, and personal allies. Even his sister in New Jersey declined to discuss her brother.

The caliber of unanswered questions around the deceased supervisor is high enough that in September the local daily newspaper editorialized against candidates using him to smear past associates now running for local office.

Follow enough cannabis industry corruption episodes, and patterns will form.

But Adam Hill’s path to corruption is a tragically specific tale.

Rule-the-World Ambitions

In one of his early scenes with the budding poet, the novelist Steve Yarbrough has just moved into the modest Vassar Street house that he’s bought with his first-year Fresno State English Department faculty salary. It’s near City College. He hears automotive sounds, looks up from his work and out the front window.

About This Story

Funding for this story was provided by the Los Angeles Press Club’s Charles M. Rappleye Investigative Journalism Award and GV Wire.

Adam pulls up in a black car that stuns Steve in a way automobiles don’t usually affect him. Yarbrough cannot recognize the model. Adam looks the new home over and asks how much the prof paid.

“$84,000,” Yarbrough answers.

“How does it feel,” asks Hill, “to know that my car cost more than your house?”

This is grad school Hill in 1988: an unknown quantity from Jersey, by way of the University of Maryland. Picture a young, high-energy Paul Giamatti. Stocky and brash at 21 and — as associates would learn — inclined to do more than brandish his flamethrower wit.

About the car: There is apparently a grandfather back east — wealthy and just as shadowy as anything else in Hill’s pre-Fresno narrative. This would be the same grandfather who introduced him to Bob Hope and got pissed when the boy expressed insufficient adulation.

If being a buzzed-about, Bob Hope-knowing rich kid didn’t impress the mostly Valley natives enough, Hill would talk about his time as a staffer for Sen. Bill Bradley. Or go on about his time on the Maryland Terrapins baseball team.

“I wasn’t any good. I just sat on the bench,” Hill would tell his English Department cadre, making it clear that, playing time or not, the experience impacted his character.

He Had a Fan in Philip Levine

Rare was the new grad student asked to present at the semester’s first Fresno Poets’ Association reading. Yet, one fall night at the art museum on First Street, Hill made that a reality.

When one of the nation’s greatest living poets has your back, precedents are for other people.

Philip Levine, the famed working man’s poet from Detroit, introduces Hill. Both are left-leaning Jews from the east in Cali ag country and their rapport was never not there. Levine owns Bonner Auditorium in this moment.

He talks up the fresh kid’s potential in a self-deprecatingly hilarious, toastmaster-worthy stemwinder. Adam Hill breathes in the applause as he approaches the mic. The wrought-language fans and would-be scribes lean forward.

The Dead Poets Society is made up of artists who pledged to suck the marrow out of life. YOLO, as the kids say.

Hill looks out into the audience, announces the name of his piece:

F–ing.

The work is signed at the bottom, in lower-case: adam craig hill

He shares his poem, a sensitively-written bit of introspection. His delivery is received and the words elicit enthusiastic applause. The power of language generates attention, more powerfully even than an exotic black car.

SLO’s Slow Embrace of Cannabis

Oprah dwells in Santa Barbara County, SLO’s neighbor to the south. From there it’s easy to mistake it for the happiest place in America. The land just feels dope, from the boundary that touches Santa Barbara up to Cambria, an ocean town whose dramatic skies call to mind romance and turbulence, sometimes at once. Physical idylls aside, San Luis Obispo has only recently stopped resisting cannabis.

Take Morro Bay’s Charlie Lynch, who back in 2006 opened a licensed medical marijuana dispensary.

“He was considered one of the pioneers of cannabis on the Central Coast,” explains Morro Bay chronicler Aaron Ochs. Lynch had been operating for a year and even joined the Morro Bay Chamber of Commerce when sheriff’s deputies raided the dispensary and threatened him with forfeiture.

Lynch found himself the martyr of the Central Coast’s anti-drug war after U.S. v. Charles Lynch drew the attention of television’s Drew Carey. En route to his conviction in Los Angeles federal court, Lynch was not allowed to use the term “medical marijuana” in his defense.

SLO feels harmonious, a territory of blues and greens. But politically? San Luis Obispo is pink, a politically-divided county that’s more right than purple. And in Our Epoch of Polarization, it’s not easy being pink. Coming of age, the cannabis legalization forebears contended with the red-ass-red of east county. On the local political spectrum’s opposite end is the eponymous city, where Hill would finally settle in as an English professor and ride college town energy to winning four consecutive supervisorial races.

As a righteous outlaw, Charles Lynch is a figure of San Luis Obispo’s cannabis past. The face of contemporary Central Coast cannabis is 36-year-old Helios “Bobby” Dayspring. Dayspring has long had hundreds of acres in Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties along with a reputation for mistreating immigrant weed trimmers and abusing a stream on his grow in Tepusquet Canyon.

He was on his way to an estimated $30 million and looking for more when an associate named Shaun DeSpain began talking about what went on between him and Adam Hill. None of the trio’s lives would be the same.

Giving Column Writing a Try

Back in 1989, just before the spring semester started, the poet walked into my newsroom. The Daily Collegian sat exactly where the new student union is, across from the fountain.

Within the graduate school, there had been collegial relationships. Graduate students taught low-level English and endured tortuous seminars and bonded. Yet, covered in black is the only way the new Collegian columnist would ever arrive. He had been frustrated with poetry — not writing it but drawing attention for his work.

Adam was the funniest of the TAs, though his humor consistently crossed boundaries into cruel territories.

One time, Professor Levine read a recent Hill creation and blindsided him with a harsh critique.

If this had been Bulldog football you’d be inclined to roll back the tape.

The future U.S. Poet Laureate insisted Hill give the poem a serious rewrite if he planned to have it published in the department’s literary journal. Hill was stunned and made defensive by the assessment. He called up Yarbrough, his faculty adviser to vent.

“Well, the way I look at it Steve, it’s you guys’ loss.”

Yarbrough responded, “That’s a little bit too brash for a writer who hasn’t got a book out yet.”

Hill was out here getting dissed, he felt, when not five living poets were legitimately famous past the form’s marginal pantheon. Toiling in anonymity for coffeehouse finger snaps was not his end game.

So, he thought he’d give column writing a try.

Wanting the Last Word

That winter I had been in a snit with the J-School and made an initiative to hire English majors as writers. Hill had written a letters section offering that called my column-writing talent into question. “A man on the edge of an idea” he labeled me. In the spirit of if-you-think-you-can-do-it-better-than-me-then-you-do-it, the man who was my first public critic became the Daily Collegian’s Wednesday columnist.

Spring ‘89 was a semester of monumental campus upheaval. Insurgent personalities such as Stacey Green, the late Andres Montoya, Daniel Alarcon, and Peter Robertson (now the university’s director of alumni connections) were impatiently pushing progressives politics to a resistant student Senate.

And the semester’s biggest development: The ag department’s debut of Super Sweet Corn.

Yo, I was just trying to get the paper out, on time and with minimal typos. The Wednesday columnist wasn’t on my mind a whole lot.

Even when I fired him.

His anti-apartheid politics dovetailed with my own protest past, but not all poets make great prose stylists. At a sentence level, his writing did little more than deliver information. The column felt like what the paper downtown was doing, but at a far lower quality. Offhand — and probably not even in person — I cut Philip Levine’s boy loose and replaced him with a couple of breezy KFSR jock whom I found amusing.

Days later, a passionate letter to the editor had been added to the metal front-office “In” basket.

When The Daily Collegian stumbles upon a writer with talent and wit, who writes about matters that are interesting, providing a new — or even twisted — vision of life he either leaves the newspaper in search of a better job, graduates or quits due to petty differences with the editor over journalistic style.

Take for example, the former Wednesday columnist Adam Craig Hill. Here was a clever guy that covered the events that affected our campus and the world…

Kevin Lombardi

It appeared that Hill had cultivated a fan base. In the fall he would go on to edit the campus literary journal Common Wages. His master’s thesis followed. In addition to a half-dozen sharp adam craig hill poems, two prose stories were included.

I do not care for them.

In the process of reporting this story, I reached out to Kevin Lombardi. Turns out that Hill forcefully encouraged him to write the letter.

On his way out of town and toward adventures in postgraduate studies at Louisiana State University, Hill stopped back by the Tower District digs of his faculty adviser. Yarbrough remained intrigued by the now-MA holder’s headstrong ways —or, perhaps because of them.

There had not been a lot of grad school poets as married to the bit as him. On this occasion, Hill pulled up in something distinctly unmemorable, not that exotic black ride.

His rich grandfather had delivered an ultimatum: Do something legitimate with my deep Jersey backing or give back the car.

Hill, it turned out, would be bossed by no editor nor grandpa. YOLO.

Painful Lessons of Bayou Country’s Racist Ways

Yarbrough is from Mississippi. He told Hill and the two grad students heading off on this Baton Rouge adventure to brace themselves. The professor wasn’t warning them off of Louisiana State’s writing program — it was recommended nationally. The setting though? It would come with toxicity. Nineteen ninety-two Louisiana wasn’t only Late-20th Century Racist South. It was Late-20th Century Racist South in the throes of David Duke’s campaign for the U.S. Senate.

Louisiana would be serving all of the trimmings.

“You’re going to see some shit down there that you haven’t seen before,” Yarbrough told the trio. Word was that Duke’s biggest donation had actually come from a supporter in Clovis, but that didn’t mean the young men were prepared.

This season of amplified racism on an everyday basis more than put them on edge. A friend of the LSU program was working at a bar on the night of a costume contest. The Halloween winner wore a Klan outfit and his girlfriend was in blackface with a noose around her neck. When the couple stepped up to take the prize, the entire bar chanted David Duke’s name.

The severe, everyday cleavage of segregation got them down as much as ostentatious shows of white supremacy. The open white supremacist took in 43% of the vote.

“It was really disturbing for some California kids. It was ugly,” recalls one of the Fresno students. “Having somebody with those views elevated gives everybody with those views license to act: Things that stay in the shadows because they should be ashamed of start coming out.”

The kids from Cali felt traumatized by an up-close view of American election culture at its edges.

The Poet’s Journey Ends

Enormous insects were rampant and accepted here, but their constant presence pushed him to the brink. For Hill, Louisiana became the scene of a lost mental health struggle. Already recognized by his cohort — no stranger to artistic temperaments — as troubled and exceptionally needful of attention, he fell apart in Louisiana, forcing them to ponder whether he was irreparably broken.

And there was an additional ugly Down South episode whose details might have died in the bayou. We do know that Adam Hill lost it, somehow, and when he again became able to contain his chaos, he provided elaborate, nakedly emotional displays of contrition to his academic band. But the poets’ journey together was done.

Reborn in San Luis Obispo

Karen Velie came to know him from the classroom, in 2006. He still had a baby face, wore a ponytail, and dressed in black, though rarely was all of his clothing the same shade.

In her mid-40s when she came back to the Cal Poly campus, Velie could have been a logo for the Self-Conscious Returning Student. In an earlier life, she had been an American Contract Bridge League teacher and tournament director.

By 2005 she was a SLOcal come home, a single mother trying to earn a degree and get better at her job.

Never a natural at the making of sentences and paragraphs, the co-founder of the investigative Cal Coast News took Hill’s class as she speculatively embarked on a second career.

“It wasn’t a class I had to take. It was a class I wanted to take,” she says.

Word got out that the political neophyte might run for a county supervisor’s seat, and that excited Velie. “I thought he was going to be fabulous for the community,” Velie told me.

He was 41 in 2007. His marriage had become a burden. Year after year of teaching creative writing at Cal Poly made it more clear that he wasn’t going to reach the heights of Philip Levine, the believer Hill believed in. Yarbrough had published his seventh book in 2006 and literary critics loved him. Each day Hill felt less likely to be hailed as the next David Foster Wallace.

On his way to divorce, the professor was journaling incessantly. He kept teaching those kids. Often, he found himself down.

The county’s District 3 incumbent was having personal problems and not expected to run for re-election. The news energized Hill. As president of the local food bank and a major part of the school’s small-business program, he had the credentials.

And, District 3 had those students.

About Those Credentials

In entering the election fray, Hill presented a smoothed-over version of his charismatic self that he had displayed in Fresno.

“At the local level, I think more success comes from being a reasonable centrist,” he told Moebius, a college journal. “I have a lot of conversations with those who won’t ultimately vote for me, but I like to understand their positions. I’d like to think that I have a moderating effect on these voters.”

As in Fresno, Hill told Moebius and constituents he had been a staffer for Sen. Bill Bradley. Yet, correspondence with Princeton’s University Archivist shows no mention of Adam Hill among the senator’s records.

And, when friends from Hill’s undergrad years in Maryland mixed with his California set, one of the people who knew him in Fresno retold the story about him riding the pine with the Terrapins baseball team.

The Maryland guys were astonished, like, “What are you talking about? Adam never played baseball!”

Had an opponent checked his credentials, the man might be alive today. Instead, Hill won a seat on the board.

‘Bonnie and Clyde Without the Crime’

By the end of his first term as District 3 supervisor, he could claim credit for his work on the 900-acre Pismo Preserve. Homelessness became a priority in SLO as it never had before.

Dee Torres, an advocate for the homeless, became Hill’s paramore.

“We’re like Bonnie and Clyde without the crime,” he told her.

At the other side of the politician’s pole was a huge dust-up with the Coalition of Labor Agriculture & Business, publicly calling the group racist in 2011 after leaders featured an entertainer who performed in blackface, as Barack Obama. Outrage ensued as the allegation struck much of SLO as over the top.

The supervisor took to the media to apologize and dial back his comments. But he had made enemies he’d never shake.

Cal Poly’s students earned the city’s most popular prof re-election. But within five years, the Fire Adam Hill Facebook page had hundreds of members.

Going to War Against the Cal Coast News

Karen Velie had sources all over SLO.

She had first worked for New Times, the weekly alternative news outlet, landing the story of a prominent Atascadero developer’s fraudulent ways, but the paper refused to run the story.

Velie eventually teamed with a seasoned journalist, and the independent Cal Coast News was born.

“I hate that bitch,” one local cannabis industry pro said of Velie, “but she’s always right.”

Meanwhile, Cal Coast News’ saturation-level local recognition made her the most empowered nosy neighbor imaginable.

In 2014, lawyer John Belsher and developer Ryan Petit transferred San Luis Consulting to Hill. Around this time, sources were telling Velie that her former writing prof had become a shameless shake-down artist.

Several years later, Bobby Dayspring began giving Supervisor Hill money orders to tilt San Luis Obispo’s cannabis policy toward the needs of his company, Natural Healing. Not long after the bribes began happening, Velie had stories about the grower-supervisor alliance on Cal Coast News. The stories were uncannily correct and were published with relentless frequency.

Now was a full-blown war. Velie says the supervisor began to harass advertisers on Cal Coast News. And people aligned with Hill attacked the journalist and family on social media.

For example, posts on multiple platforms falsely accused Velie of murdering her daughter. During that time, her family dog was killed, Velie said.

Cocaine Takes Hold of Hill’s Life

As is often the case with cocaine abuse, it can be difficult to discern which came first, the powder or the corruption. However, taking into account the onslaught of bad decisions that dominated Hill’s world from 2014 on, it’s pretty safe to award First Prize to yeyo.

For some in the gallery, a dead giveaway was Hill’s new opponent in health: Crohn’s disease. That he would eventually go public with his own case of the colon dysfunction common with heavy coke users cinched the assessment. (In 2022, Dayspring acknowledged his own Crohn’s suffering in court documents.)

Clue two: Adam Hill was now given to outrageous public behavior. Where the San Luis Obispo Tribune had praised the first-term Hill for his civility, by 2014 he was Goofus to fellow board liberal Bruce Gibson’s Gallant. Had he not been based in a district where the hijinks struck many as humorous or rad, the scenes might have hurt him.

“Sometimes Adam, even though he was a very intelligent guy, he was sometimes, in his anger, inarticulate,” explained Aaron Ochs, the Morro Bay author and entrepreneur. “In my private conversations with Adam, he would explain the issue in terms that were very clear to me. But (in session) his anger would bubble to the surface and the camera was focused on him and he would say things.

“Or he would write things on Facebook.”

Stuff Those Envelopes, Folks

One cannabis consultant told me he attended a 2014 meeting in which a prospective operator asked how to get ahead in the licensing process. The supervisor, he said, passed out envelopes and told the applicant and everyone else in the room to fill them up if they wanted to get in the game.

Some in that room thought Hill was joking. Others put a thousand dollars in their envelopes and gave them to Hill. The makeup of San Luis Obispo’s infant industry was being determined in these rooms. The license qualification process for this once-in-a-lifetime industry opening was being usurped to serve local favorites.

“They were all neighbors and they all held together,” said one rejected applicant. “They were laying out this plan, and none of us knew that.”

The money orders kept coming on behalf of Natural Healing Center, $32,000 in total. Occasions to lay cash contributions on the supervisor became to be known as “birthday parties” because gifts would not count against campaign contribution limits. Which only makes sense if you ignore the fact they were bribes.

Messiness isn’t synonymous with erratic behavior, but it’s close.

Hill told a constituent to f-off in 2018, and the mainstream press caught wind of it. He apologized in his familiarly frank and relatable fashion, but this time he went public with his depression struggles. Hill took time off but did not return with anything like a meaningful grip on his life. From the dais, on a July night in 2019, Hill texted Dayspring the sentence that finally brought him within fame’s proximity:

“Your industry should give me one giant French kiss wrapped in money after my work today.”

Of course, no other supervisor on the dais knew Hill had texted this message of collusion. Neither did anyone in the gallery. But the FBI was watching.

A Life in Freefall

Back when he was still immersed in the study of writing and literature, Hill was asked by an English Department crony why he signed his poetry in lowercase.

“Are you self-styled e.e. cummings?” asked Eric Lombardi.

“The reason it’s in lowercase,” Hill answered, “is because I consider it an unfinished poem.”

If life were a poem, his was now a rhyme cratering wildly, toward an end just past his imagination’s limits. Rewrites were not on the table.

In the days before his first suicide attempt of 2020, Hill let his driver’s license expire.

The last campaign had been backwater political brutality at its contemporary ugliest. An allegation of inappropriate behavior emerged from Hill’s time teaching at Cal Poly. And in February 2020 — one month before the election — a trove of wildly explicit emails about Karen Velie and others was given to a talk radio host.

The name on the email account was “Sal Krill” and the email came from the Shell Beach address. Hill denied that the emails came from him. His District 3 opponent, Stacey Korsgaden, took an early lead on the third of March. COVID was raging and the world felt entirely askew. Counting was slow. Korsgaden gave optimistic interviews, though only 304 votes separated her from the incumbent.

Hanging over the election was the influence the incumbent had peddled. It hung above Adam Hill like the sword of Damocles.

On March 11, he had drawn enough votes to win, barely. That night word reached San Luis Obispo via Cal Coast News that the FBI had searched his County Center office and Shell Beach home.

That he had tried to take his life by drug overdose would not become public until month’s end.

Some residents didn’t believe it, critics thinking Hill had contrived the suicide attempt, to gain sympathy or distract from the investigation. Others took the try as a consciousness of guilt. Supporters outside of the bubble said he was overwhelmed by the overall swirl of events.

On April 12, Hill resigned as board chair but did return to working via Zoom. By July 12, he had checked back into a care facility. His estranged wife, Dee, had returned. She emailed local media.

“Persistent, and at times, painfully debilitating depression, has necessitated my seeking more intensive and focused treatment at a residential health program,” the San Luis Obispo Tribune quoted the supervisor as saying.

A Tangled Web Comes Publicly Undone

COVID summer raged on — fires to the north, Black Lives Matters highway protests frightening much of the predominantly White region — and grew progressively horrific. On July 23, Dayspring collaborator Shaun DeSpain was found dead by his girlfriend in his San Luis Obispo home. His cause of death was listed by the county coroner as the combined effects of cocaine, ethanol, trazodone, alprazolam, and nitrous oxide.

For months before his March suicide attempt, Hill had only been in touch with Dee via text. Now they were closer. She checked on him regularly. One day, she drove to Shell Beach for a look-in. She found Hill in tears. He confessed that had an affair while they were still together, and the woman had become an administrator working for Hill, in his county office. She was coming forward with an allegation of harassing, post-breakup touches.

Hill did not tell her that his tryst happened to be with the daughter of the first SLOcal to be licensed to grow cannabis.

Days later — about 24 hours before the inappropriate relationship item was to go on the supervisors’ meeting docket — Dee received a call from a friend in the Sheriff’s Office. Adam was at the hospital, unresponsive and alone. He had taken a large amount of cocaine that, working in concert with his antidepressants, stilled his life. Hill was 54.

“When he finally committed suicide, people were surprised and devastated, because they thought he was making progress,” Ochs said.

In Memoriam

“What was remarkable about him,” Supervisor Bruce Gibson told New Times, “is I never came across anybody as committed to the full breadth of his constituency — especially those who had little in the way of material resources. Those who had the least in this world had a true champion in Adam.”

In the wake of Hill’s death, Gov. Gavin Newsom vowed to “honor the candor with which he shared his mental health journey.”

Others weren’t as kind in summing up Hill’s complicated life.

He is “the Trump of San Luis Obispo,” longtime Democratic party activist Stewart Jenkins told me.

Epilogue

On May 27 of this year, Helios Dayspring was sentenced to 22 months in prison for tax evasion and bribing Hill. Remarkably, he had paid the Internal Revenue Service just under $3.5 million in ordered restitution before his sentencing.

Prosecutors wrote in a sentencing memorandum that Dayspring “had one goal: build a cannabis empire. To accomplish that goal, he would not let anything get in his way, including the law.”

Dayspring checked into Mendota’s Federal Corrections Institution on Aug. 30, but before doing so submitted in a civil court filing that he’d bankrolled San Luis Obispo’s two biggest dispensaries to the tune of $1.8 million in undocumented dollars.

Last year, a redistricting effort cut Adam Hill’s District 3 in half.

“To me, this is tragedy,” the novelist Yarbrough said. “Adam had a very large personality and he was charismatic. He could very easily have done a lot of good.”

Corrections to this Article

The previous version of this article contained inaccurate information about CalCoastNews, Karen Velie, and information attributed to Velie. The article has been corrected.

About the Author

Donnell Alexander is an author and freelance reporter based in Los Angeles. From 2018-2020 he co-hosted The WeedWeek podcast, which was named to Quartz and Forbes best-of lists. Alexander contributes print reporting to The Guardian, Insider, Cannabis Law Report, and WeedMaps. He has written three books, including “Ghetto Celebrity: Searching for My Father in Me.”

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

The Birth Rate Is Plunging. Why Some Say That’s a Good Thing

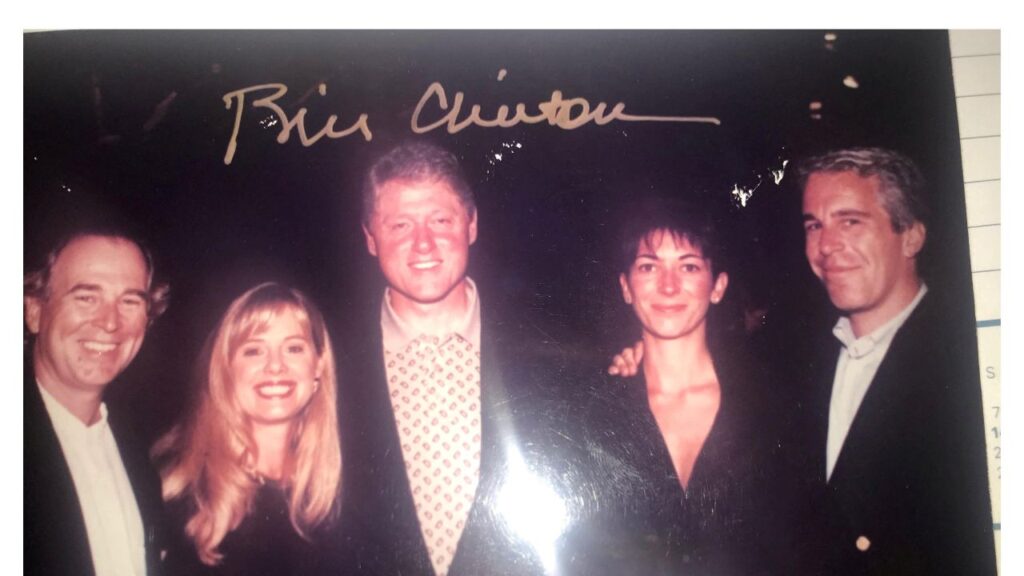

Bill Clinton to Lawmakers Investigating Epstein: ‘I Saw Nothing’

Mac the Cat Is Guaranteed to Spice Up Your Life