Share

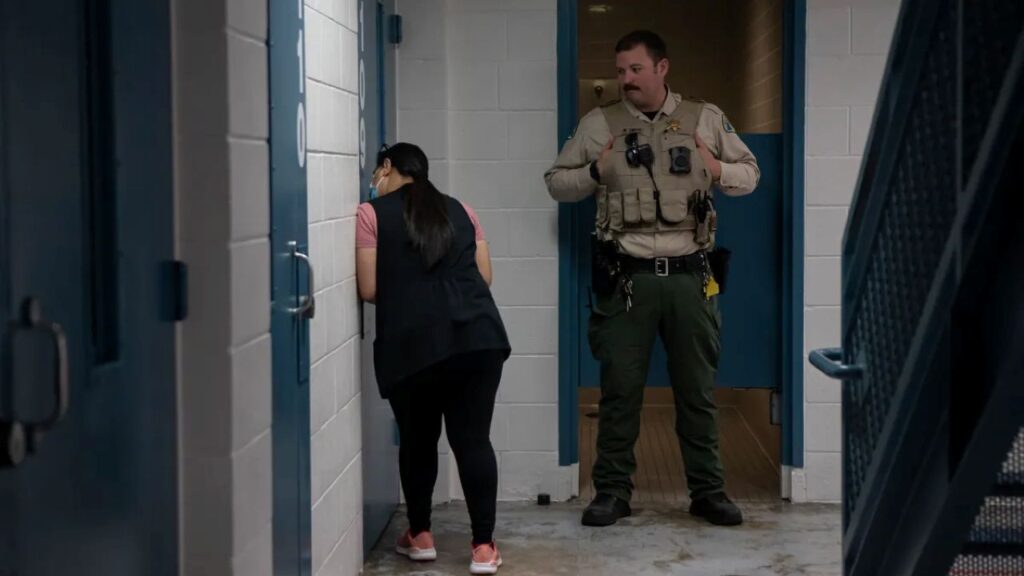

SACRAMENTO — After years of fruitless debate, California now is on the verge of phasing out its state-operated juvenile prison system, a move hailed by reform advocates and criticized by counties that would assume responsibility for some of the state’s most violent criminal youth.

The bill state lawmakers sent to Gov. Gavin Newsom in the final hours of their annual session generally follows his latest plan to unravel the Division of Juvenile Justice, which has about 750 youths in four facilities, including 70 in a firefighting camp.

But legislators added what advocates said are needed safeguards and standards for the hundreds of millions of dollars that would eventually flow to counties to house and treat juveniles who now are funneled to the state lockups — restrictions that county organizations said hobble their ability to provide proper care.

“That kind of systemic transformation is exactly what I think we’re learning needs to happen in this time when you’ve seen much tumult around how the criminal justice system operates and whether it’s fair and equitable particularly as it relates to the treatment of kids of color,” said Chet Hewitt, whose Sierra Health Foundation manages the reform group California Alliance for Youth & Community Justice.

It was among numerous criminal justice measures lawmakers sent to Newsom, including bills to create a state-level re-entry commission; allow parolees to earn a swifter end to supervision; shorten probation terms; and restrict the use of prison informants. Another bill would allow judges to send misdemeanor offenders to diversion programs over prosecutors’ objections, and lower the age limit for the state’s elderly parole program from 60 to 50.

Newsom in May proposed phasing out the juvenile prisons, arguing that it “will enable youth to remain in their communities and stay close to their families to support rehabilitation.” Counties would stop sending juveniles to state lockups after July 1.

California would instead create an Office of Youth and Community Restoration and send grants to counties to provide custody and supervision.

“We’re one of the few states that doesn’t have a state agency that oversees the youth justice system and can effectively work with other youth-serving agencies” like child welfare and education providers, said attorney Frankie Guzman, director of the California Youth Justice Initiative at the National Center for Youth Law.

Guzman committed armed robbery at age 15 and spent six years in California’s youth prisons until he was freed in 2004. There is far more emphasis on rehabilitation today, but he recalled that “all I was offered was a cup to pee in (for drug tests) and dangling handcuffs in front of me. That’s all I got in terms of re-entry support.”

As of this year, 14% of those in juvenile prisons are serving time for murder, 37% for assault and 34% for robbery. There are 25 females. A disproportionate 30% are Black and nearly 60% Latino. They will stay in state custody until their time is served or they reach age 25, while those brought into the new system starting next year could stay in county juvenile programs until the same age.

The Legislation Projects That the State Would Provide Counties With Nearly $40 Million

The firefighting camp would still train delinquent youth. A separate bill would let former inmate firefighters petition to erase their criminal records to help them get jobs.

The legislation creating the county-run system was opposed by organizations representing counties, chief probation officers and county behavioral health directors, who all said they were left out of the final negotiations.

They said the new system doesn’t give counties enough flexibility, and the funding formula doesn’t do enough to help those counties that have relied most heavily on the state system and thus would have to do the most to prepare for handling their own caseload.

“They’re trying to save money on the backs on counties, and that is very concerning when they wouldn’t work with us on how to implement it successfully,” said Darby Kernan, deputy executive of legislative affairs at the California State Association of Counties.

Chief Probation Officers of California Executive Director Karen Pank said the shift could harm successful existing programs for troubled youths, while the state correctional officers’ union said state facilities are best equipped to handle the most serious offenders.

Hewitt, who was sent to New York City’s Rikers Island for gang-related offenses at age 16, argued youths who commit less dire offenses should be diverted to treatment programs, leaving probation officers to focus on those who commit the most serious crimes.

The legislation projects that the state would provide counties with nearly $40 million in the first year to keep custody of about 177 youths who otherwise would have gone to state lockups. That grows to $209 million for 928 youths by the 2024-25 fiscal year and thereafter.

“They wanted $209 million with no strings attached,” said Guzman, but the legislation among other things requires counties to create advisory boards, including at least three youth justice advocates, to develop rehabilitation plans.

The funding formula was developed so that more progressive counties can keep funding their programs, Guzman said, but “we don’t reward bad-acting counties for overusing (youth prisons) and not developing alternatives.”

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Mountain Lion Trio Caught on Camera in Shaver Lake