Share

Tony Thurmond seems to be exactly the man that his most loyal backers hoped (and his opponents feared) he would be.

by Ben Christopher

CALmatters

“If it were not for the education, my cousin who took me in, countless mentors, that I would easily have ended up in California state prison instead of serving as California’s superintendent of public instruction,” he said. “We owe this to all the students in our state.”

That philosophy, he said, informs his fairly dim view of charter schools, which he characterized as benefiting certain students at the possible expense of others.

“I think there’s a role for all schools,” Thurmond said, including charters—publicly funded but privately managed schools that supporters say offer valuable educational alternatives to children, but which critics say undermine traditional public schools. “But I do not believe that the state should ever open new schools without providing resources for those schools. I do not believe that education is an environment for competition.

Newsom Asked Thurmond to Put Together a Task Force

“Here’s my concern: you cannot open charter schools and new schools to serve every single student in our state,” he continued. “If you take the competition approach, that means some students, a lot of students, will be left behind. And again, I don’t believe that that’s what our mission is. I believe that the promise that we make to each other in society is to provide opportunity to get an education, to live a better life, to be able to acquire what you want through your hard work for yourself and your family. So for me that means that competition is OK in some environments, but when it comes to education we’ve got a responsibility to make sure that every single student gets an education.”

In the 2018 campaign, Thurmond and challenger Marshall Tuck tried to convince voters that they were not as extreme as their opponents sometimes portrayed them to be.

Tuck, with a background in charter schools and over $30 million of charter-backing dollars behind him, stressed his progressive credentials, while Thurmond, supported by teachers’ unions, insisted that he would not be beholden to organized labor.

Thurmond won by 2 percentage points.

Following the teachers’ strike in Los Angeles, where charter school growth has exacerbated tensions in the district, new Gov. Gavin Newsom asked Thurmond to put together a task force to study the fiscal impact that charters have on school districts. Because schools receive state funding on a per-pupil basis, charter skeptics argue that when students transfer to a charter, it leaves the traditional school unable to meet various fixed costs, such as building maintenance and debt.

The task force is composed of public school district superintendents, union representatives and charter school groups. But Thurmond made his position clear.

Underlying Problem Facing Districts Is Not Charters

“There has been, for many districts, a significant fiscal impact and loss of revenue directly attributed to the growth of charter schools,” he said, citing a report from the left-leaning research center In The Public Interest, which estimated that San Diego Unified School district has lost $66 million while Oakland Unified has lost $57 million. “We have to have tough conversations including the fiscal impact of charter growth on the traditional districts and come out in a way where we can do what’s best for all of our students in the state.”

Disputing the numbers Thurmond citied, he said the underlying problem facing districts is not charters, but insufficient funding.

“I have to believe that part of the debate around fiscal impact and the appropriate role and the appropriate rate of growth for charter schools is mostly being dictated by the environment of scarcity that we’re all living in,” he said. “We have not met the challenge in California of fully funding our public schools—and that’s a place where we can call agree.”

True enough, Thurmond pointed to insufficient state funding as the source of virtually all that ails the state’s public school system.

“We are still 41st in the nation in per pupil spending,” he said, a number that takes into account the cost of living in each state. “No matter what you do, until you resolve that, we’re going to continue to see challenges.”

Challenges Blamed on a Lack of Funding

Among the challenges he blamed on a lack of funding:

- The achievement gap between disadvantaged and privileged kids. As CALmatters has reported, less than a quarter of black and Latino students in California are meeting state math standards on statewide tests.

- The decline in enrollment in unaffordable districts like Palo Alto. When a public school board member from East Palo Alto asked what the state could do to help the district cope financially with declining enrollment rates, Thurmond pointed to the need for workforce housing and magnet schools, but ultimately, he said “clearly we need more funding.”

- The disparity in the ability of local school districts to borrow. According to a CALmatters analysis, the wealthiest school districts are in some cases able to borrow more than 300 times as much than low-income districts to fund the repair and expansion of buildings. Thurmond’s response: “I don’t know that districts can do it all by themselves,” arguing that the state should kick in more to even things out.

- The recent teachers strikes in Oakland and Los Angeles, as well as the ongoing financial difficulties at the Sacramento City Unified School District. “There’s not much to cut,” he said of Sacramento. “Unless something miraculous happens, that’s a district that is also going to need a financial bailout from the state.”

But Thurmond also blamed the recent flare-up of labor action across the state on a longstanding lack of trust between teachers’ unions and the school district administrators. And the fault primarily lies with the administrators, he said. Before serving the state Assembly, Thurmond was a West Contra Costa Unified school board member, and he helped mediate the recent strike in Oakland.

“There is a history in the state, and maybe in the country, of times when school boards would sort of hide the revenue that was available…as a way of avoiding having to negotiate salaries,” he said.

“That is not representative of the conduct of the vast majority of the roughly one thousand school districts across the state,” said Troy Flint of the California School Boards Association. But he also agreed with Thurmond that the primary issue is funding.

A growing Source of Financial Stress for Many Districts

“The battle is not between labor and management. The focus needs to be on our legislators and leaders in Sacramento, and forcing them to confront the fallout from being 41st in the nation in school funding,” he said.

“Everyone deserves a pension,” he said. “I think we’re going to have to figure out how we’re going to pay for it.”

He added that he has formed a task force to identify new sources of funding. One idea: reform the state constitution so that commercial property owners pay property taxes based on the market value of their property, rather than the purchase price.

That tax tweak to Proposition 13, known as “split roll” will be on the ballot in 2020.

Listen to CALmatters March 21 discussion with Tony Thurmond at San Francisco’s Commonwealth Club here.

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

Categories

The Birth Rate Is Plunging. Why Some Say That’s a Good Thing

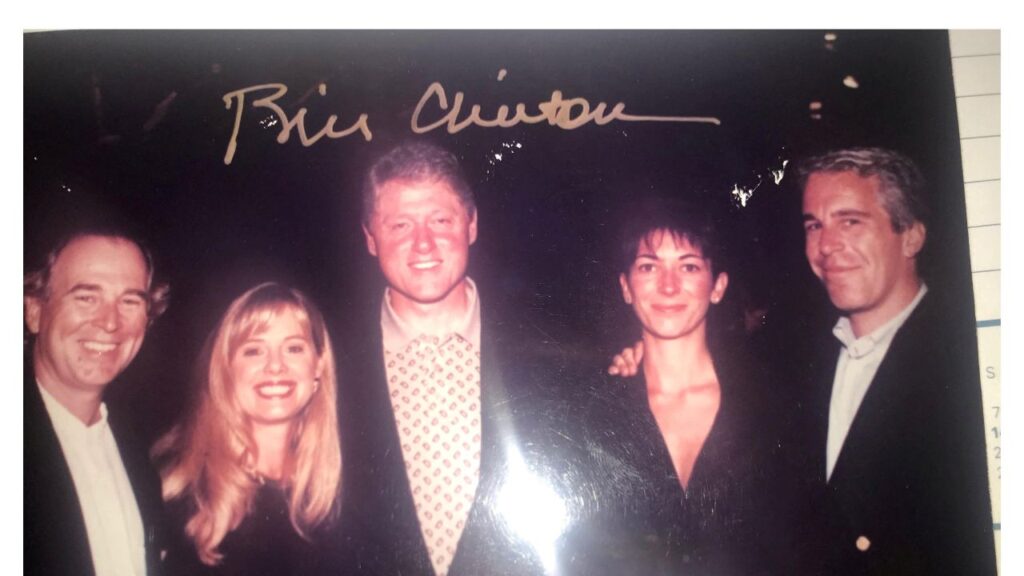

Bill Clinton to Lawmakers Investigating Epstein: ‘I Saw Nothing’

Mac the Cat Is Guaranteed to Spice Up Your Life