Share

Opinion

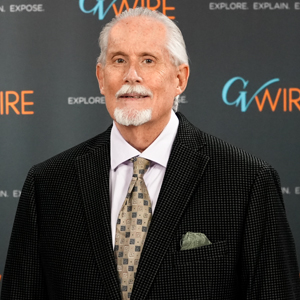

By Bill McEwen

That’s something we should never forget.

The ingenuity, enterprise, capital investment and back-breaking labor of immigrants are splashed all over Fresno.

You can see their vines, their buildings and their legacies — east to west and north to south.

It’s a tradition that continues to this very day, as new arrivals put down roots here and become an integral part of the community.

Today we debate the value of immigration. Open borders? Closed borders? Guest-worker programs?

The United States and the world are much different than they were in 1872, when the Central Pacific Railroad’s Leland Stanford saw Anthony Easterby’s bountiful fields of grain and decided a railroad station belonged at what is now downtown Fresno.

Our country was trying to begin mending the gaping wounds of the Civil War, the four-year battle over slavery that killed at least 620,000 soldiers. California’s Gold Rush had played out, but not before driving Native Americans off their lands and destroying much of their fish and game habitat.

But a saving grace had taken hold: The First Transcontinental Railroad — with Stanford hammering a ceremonial gold spike — opened in spring 1869. Our country’s economy was jump-started again. California became a favored destination.

The California Immigrant Union

Men like Stanford and Frederick Christian Roeding, himself a German immigrant, were among the organizers of the California Immigrant Union. The organization sought to convince people all over the United States and Europe to move to California.

A story in the Oct. 14, 1872, Daily Alta California newspaper detailed some of their efforts. Here is a paragraph: “The number of callers at the office for information concerning public and private lands, mostly during the past year, was as follows: Americans, 1,192; foreigners, 460. Total, 1,652.”

Some things haven’t changed. Even then, those promoting Fresno boasted about its convenient location. “Only Nine Hours Ride From San Francisco By Rail,” crowed the Expositor ad.

The ads worked exceptionally well for German immigrant Bernard Marks. Wrote John Panter in a 1994 article for The Journal of the Fresno City and County Historical Society:

“Quite simply, the Central California Colony was born of the dreams of a man named Bernard Marks, sown into the land of William S. Chapman, watered by the canals of Moses J. Church, and nurtured to fruition by the people who came to live there. The accomplishments of all these people would earn the colony the distinction of being the first successful agricultural colony in Fresno County.”

Italian, Swiss and French Immigrants

This brings us back to Easterby, an English immigrant, Napa railroad owner and former sea captain. His collaboration with Church on creating a canal system to irrigate Fresno’s fertile fields made the colony concept possible.

For example, 20-acre lots in the Scandinavian Colony sold for $300 and you had five years to pay off the purchase. The idea was that you could build a house and farm the remaining area. And you didn’t have to be Scandinavian to purchase land there.

“Any good man or woman may become a settler in this colony without regard to nationality,” said a story in the March 15, 1879, edition of the Rural Pacific Press.

These colonies and many more formed Fresno’s foundation. Settlers landed here from San Francisco and other American cities. But Italian, Swiss and French immigrants gobbled up the 20-acre parcels, too.

The Scot Who Perfected the Fresno Scraper

It was James Porteous, a Scot entrepreneur and blacksmith, who perfected the “Fresno” scraper that cleared the dirt for irrigation ditches and canals. His Fresno Agricultural Works manufactured these scrapers, which were sold all over the world.

“(T)he French have used them in railroad construction in Syria, the British in South Africa and India, and the Japanese and Russians in the Far East,” wrote Wallace Smith in his 1939 first edition of “Garden of the Sun,” a history of the San Joaquin Valley.

Porteous’ company, which was founded in 1876, continues as Fresno Ag Hardware at 4590 N. First Street.

We know Roeding, of course, for donating the land and designing the Fresno park that bears his family’s name.

Kearney Park is named for Martin Theodore Kearney, who was born in Liverpool, England, and was the son of an Irish laborer. His family moved to the United States in 1854, and Kearney took a steamship from Boston to San Francisco in 1859. He eventually landed in Fresno. From these humble roots sprang the “Raisin King of California.”

Immigrants Put Fresno on the Sports Map

Fresno boasts two world boxing champions since it incorporated in 1885.

Young Corbett III, who sold newspapers on Fresno street corners in his youth before winning the welterweight title in 1933, was born in Potenza, Italy. His birth certificate says, “Raffaele Capabianca Giordano.”

Hector Lizarraga, who was born in Mexico, came with his family to the Valley to work the fields. He punched his way to the featherweight crown in 1997.

German immigrant Herman H. Brix built the mansion bearing his name at 2844 Fresno Street. He found oil in the Coalinga hills in the early 1900s and made his fortune. Then he moved on to developing and selling properties.

You know the beautiful “Fresno Best Little City in the U.S.A.” arch on Van Ness that marks an entrance to Fresno?

The late Frank Caglia, an Italian immigrant, refurbished the original arch, dressed it in neon and added the “Best Little City” tag.

“I’m an import at birth and this city has been real good to me,” Caglia told The Fresno Bee in 1980. “If I had stayed in my little town in Italy, I would never have had what I have now.”

Tending the Fields, Crops and Dairies

Immigrant labor helped build the Valley’s irrigation canals and railroads. It was immigrants who often picked the crops and loaded the wagons that delivered the produce to the train stations.

Del Rey farmer and author David Mas Masumoto writes in his book “Epitaph for a Peach” of the sweat and toil that has gone into our fields:

“I sometimes picture my farm as a battlefield with troops of people struggling with nature in a hundred-year war. Germans, Italians, Chinese and Japanese, Armenians, Filipinos, and Mexicans — their voices have sounded over this farm, their families have walked these rows.”

Hagop Seropian and other family members were the first Armenian arrivals in Fresno. They settled here in 1881 from Massachusetts, where the winters were too cold for their liking. They, too, promoted the Valley and the virtues of farming to their Armenian friends on the East Coast and in the “old country.”

A volcanic eruption in 1957 caused heartbreak and devastation on the island of Faial and displaced thousands of Azoreans. That tragic event moved U.S. Rep. Harlen Hagen of Hanford to sponsor legislation granting visas to 1,300 families. Congress twice extended Hagen’s Azorean Refugee Act of 1958, opening the Valley’s doors to another wave of immigrants.

Fifty years later, a story by McClatchy’s Michael Doyle pointed to the 2000 Census, which identified 1.1 million Portuguese-Americans living in the United States — about 330,000 in California. A 2008 House resolution asserted that Portuguese-Americans owned roughly half of the San Joaquin Valley’s dairy farms by the 1970s.

Courtesy Pop Laval Foundation.

Far From Laos, The Hmong Make a Home Here

After fleeing communist-held Laos, Hmong refugees began making their way to California in the 1970s and into the Valley. In 2004, with the closing of an unofficial refugee camp in Thailand, about 3,000 Hmong resettled in Fresno.

The Bush administration made that decision because of the success that earlier Hmong refugees had assimilating into our city. In addition, many of the new arrivals had relatives here. Fresno’s political and religious leaders also embraced the opportunity to help these immigrants realize the American Dream.

Last spring, the Los Angeles Times profiled the Thao Family Farm, which grows and markets “some of the best and most revered produce in California.” The Hmong family is one of those that bolted Laos and planted roots in Fresno.

“The 34 acres translates into about 25 of usable farmland, where all the picking, weeding and planting is done by hand. The farm was founded by Vang Thao, 58, and his wife, Khoua Her, 52, in the early 1990s. But they didn’t actually purchase and move to their current property until 2010,” wrote Noah Galuten.

“Now, acclaimed Los Angeles chefs … rave about Thao Family Farm’s produce.”

Immigrants Still Starting Anew in Fresno

Just like those before them who found Fresno from places all over the world, about 200 Syrians refugees — pushed out by the murderous regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and civil war — are starting over here.

The good weather, the relatively cheap (by California standards) rents and the opportunity to succeed are the draws.

Some Fresnans aren’t happy about the presence of Syrians refugees.

But the cycle continues. Immigrants helped build this city from its humble beginnings, and they’re helping build it today.

Categories