Share

By Sabrina Tavernise

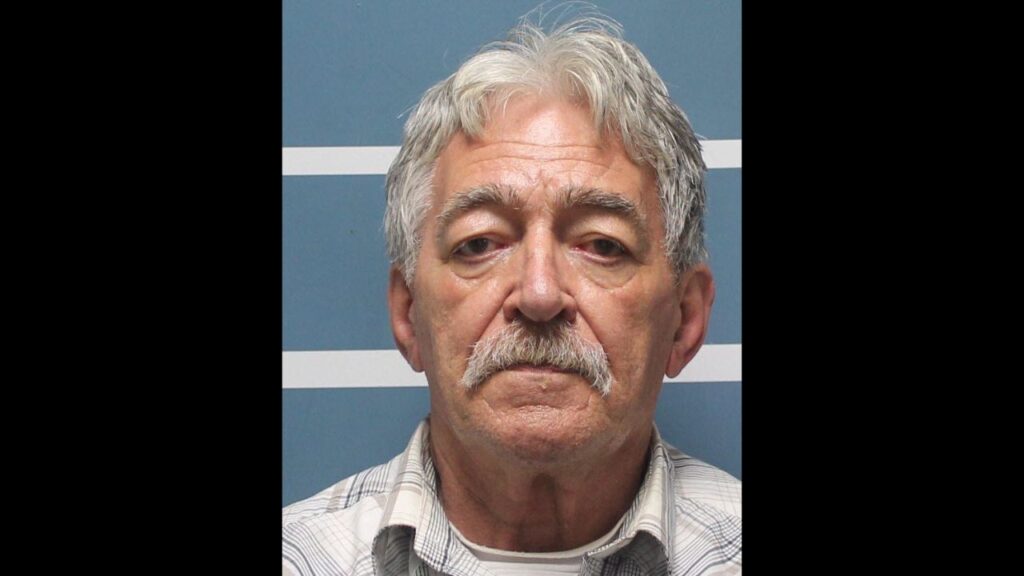

WENDELL, N.C. — Yoselin Wences grew up with a constant refrain from her parents, immigrants from Mexico who became a landscaper and a cook.

“The mindset was, ‘Don’t be like us,’” she said. “’Don’t get married early. Don’t have children early. Don’t be one of those teen moms. We made these sacrifices so that you can get educated and start a career.’”

She followed that advice, and now, at 22, Wences, a junior at North Carolina State University, will soon become the first member of her family to graduate from college. When asked about children, Wences replied that for her, they were years away.

“Probably around 34 or 35,” she said. “That age range seems ideal to me.”

As fertility rates across the United States continue to decline — 2017 had the country’s lowest rate since the government started keeping records — some of the largest drops have been among Hispanics. The birthrate for Hispanic women fell by 31 percent from 2007 to 2017, a steep decline that demographers say has been driven in part by generational differences between Hispanic immigrants and their U.S.-born daughters and granddaughters.

It is a story of becoming more like other Americans. Nearly two-thirds of Hispanics in the United States today are born in this country, a fact that is often lost in the noisy political battles over immigration. Young U.S.-born Hispanic women are less likely to be poor and more likely to be educated than their immigrant mothers and grandmothers, according to the Pew Research Center, and many are delaying childbearing to finish school and start careers, just like other U.S.-born women.

Helping to Drive a Major Shift in the Country’s Fertility Patterns

“Hispanics are in essence catching up to their peers,” said Lina Guzman, a demographer at Child Trends, a nonprofit research group.

The Hispanic decline is helping to drive a major shift in the country’s fertility patterns. Child Trends found that 2016 was the first year in which American women ages 25 to 29 did not have the highest birthrate. Instead, the rate was highest among women in their early 30s.

In the last year, as demographers have tried to better understand what is driving the country’s overall declining fertility rate, they have looked more closely at the data broken down by race and ethnic group.

The fertility rate for Hispanics — defined by demographers as people who report they are of Hispanic origin on birth certificates — dropped to 67.6 from 97.4 births per 1,000 women. By contrast, the rate for non-Hispanic whites fell by 6 percent to 57.2, and by about 12 percent for blacks to 63.1, according to Child Trends.

The implications of the Hispanic decline are broad. With the white population shrinking, Hispanics account for the majority of the population gains in the United States. And while their fertility rates are still the highest for any major racial and ethnic group, the steep drops in recent years are having an effect.

The United States population grew by just 0.6 percent last year, the smallest increase in 80 years, according to Ken Johnson, a demographer at the University of New Hampshire. He noted that, at current rates, young Hispanic women will have an average of two children, down from three just a decade ago.

The largest decline in Hispanic fertility rates has been among women of Mexican heritage, Guzman said. That is significant for the nation’s fertility patterns because of the sheer size of the Mexican origin population, which accounts for nearly two-thirds of all Hispanics and around 11 percent of the U.S. population, according to the Pew Research Center.

Spending More Time With Children Who Were Not Hispanic

Wences’ parents, who came to the United States permanently in the mid-1990s, met on a tobacco farm and settled in a rural patch of Wake County, which contains Raleigh and its suburbs. Soon after, when her father was 21 and her mother was 23, Wences was born.

There weren’t many Hispanic families in the area at the time. Wences recalled spending more time with children who were not Hispanic and discovering differences. Their parents were much older than her parents. They worked at desks, not outside.

“I remember mentioning my mom had my sister when she was 15 and I kind of got the side eye,” she said.

Wences once bragged to a friend, as they walked on school grounds just before a snowstorm, that her father was the one who sprinkled the salt crunching under their feet. Her father, Enrique, later told her not to talk about his work.

“He said, ‘You don’t want to be like me, mija,’” she recalled, using a Spanish abbreviation for “my daughter.” “I want you to go to school. I want you to do better than me.”

Enrique Wences, 43, said he was self-conscious that he did not finish high school.

It was a regret that would power him through seven-day workweeks for 25 years so that his daughters could get an education.

One of the happiest moments of his life was when Yoselin called him from her car in the parking lot of Wake Technical Community College, where she was studying for an associate degree, to tell him that N.C. State had accepted her transfer application.

The Fertility Rate for Hispanic Women Dropped by About 47 Percent

Wences said that if she got pregnant now, she would probably have to drop out of college.

“I’d feel embarrassed that the sacrifices that my dad made up to this point would be going down the drain,” she said.

Between 2007 and 2017, the population of Hispanic women of childbearing age in Wake County grew nearly 50 percent, drawn by a booming local economy. Yet the fertility rate for Hispanic women dropped by about 47 percent, according to Johnson. The rate for women who were not Hispanic dropped by about 16 percent in the same period, he said.

Birthrates tend to follow economic cycles. The fact that the U.S. rate has not picked up along with the economy in recent years has puzzled demographers. In a survey late last year, the top reasons young women gave for delaying children involved money — children were simply too expensive.

But several young women interviewed for this article said that was not the case for them. Many came from large extended families with aunts and cousins who would care for a baby if need be. Many of those women had been raised by siblings in Mexico as their parents worked.

“I have a very supportive circle,” Wences said, adding that if she wanted to go through with having a baby, her boyfriend’s parents would probably help. “But what is the point of having a child if you can’t enjoy it?”

Having Children Later Might Be Common for Young Americans

Some women said their lives were so busy — many worked full time while also going to school — that they did not have time for friends, never mind boyfriends. Many lived at home in distant suburbs, instead of on campuses in the city, making socializing difficult.

“At the moment, I am not thinking about dating anybody,” said Bianca Soria-Avila, 28, who is in her last year at Wake Tech in Raleigh. “I don’t have friends. I don’t want to talk on the phone or to go out. I need to graduate,” she said.

Having children later might be common for young Americans, but it is unusual for Soria-Avila’s older Mexican-American relatives, who often react with raised eyebrows when they ask her age at family gatherings.

“They laugh and say ‘When I was your age, I already had four kids,’” she said. “I tell them if I had kids now, I wouldn’t be able to do what I want to do.”

For now, Wences said she was focused on finishing her bachelor’s degree in psychology. Her associate diploma hangs on her father’s living room wall.

“My wish for her is she keeps on in her education and becomes somebody,” Enrique Wences said. “I want her to be comfortable, to have control over herself and her life.”

So far, his wish is coming true.

“She came out 100 percent what I hoped,” he said.

© Copyright The New York Times News Service, 2019

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories