Share

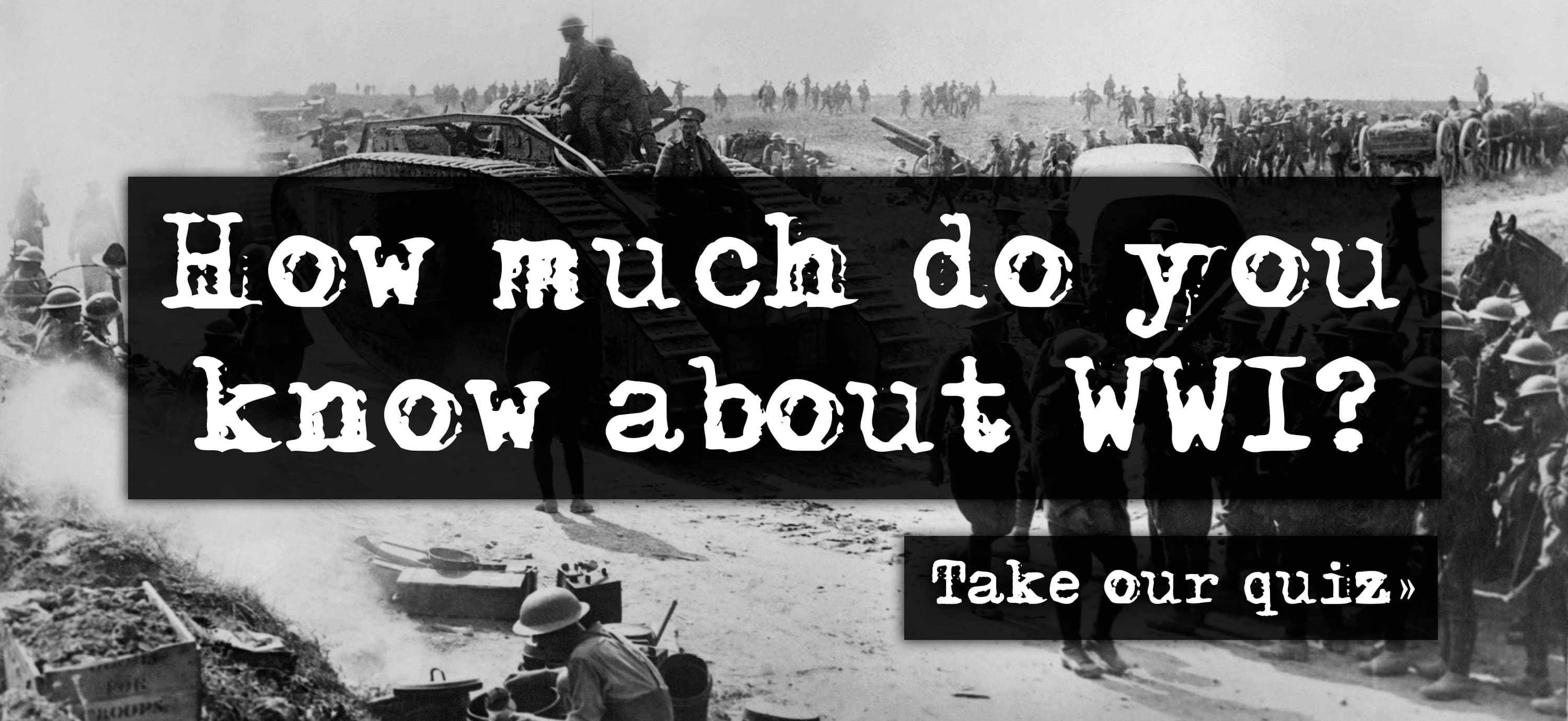

On April 2, 1917 President Woodrow Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress to request a declaration of war against Germany.

Opinion

Gordon Stables

It was a somewhat surprising turn of events. Earlier in his presidency, Wilson coined the phrase “America First,” and his supporters proudly waved banners at the 1916 Democratic National Convention extolling, “He Kept Us Out of War.” Now Wilson was explaining that “Neutrality is no longer feasible or desirable where the peace of the world is involved.”

Like many scholars of the presidency, I think it is important to examine how presidents justify the use of military action. These presidential calls to war provide the foundation for public understanding of the conflict.

A Pivotal Moment

And while many presidential calls to war are well-known, Wilson’s presidential voice – even at this pivotal moment – is oddly quiet to modern audiences. Perhaps this is because he was the last American president who never had his voice amplified over radio, television or the internet.

Wilson is commonly remembered as the president who traveled to Europe at the conclusion of World War I and tried to rally the world to support the terms of peace.

He saw these negotiations as paving the way to a new era of global cooperation. Wilson would later win the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in founding the League of Nations, the first global organization devoted to peace. But, despite his enthusiastic lobbying, the U.S. never joined.

Wilson could not convince Congress that a strong and neutral arbitrator was the best way to avoid future conflicts. Instead of pursuing “a peace without victory,” the triumphant allied nations punished the Axis powers and set the stage for another terrible war. It would take the second tragedy of WWII to convince both the U.S. Congress and other world leaders to embrace a global organization in the form of the United Nations.

Wilson was a reluctant advocate for American interventionism, but his war address to Congress provided a foundation for American foreign policy for the next century. In it, he had to convince Americans to accept massive costs to help create peace in a faraway land.

Little of the 20th-century history as we know it seemed inevitable at that moment when Wilson, who had come to the presidency with only two years of experience in elected office as governor of New Jersey, faced angry crowds of antiwar demonstrators threatening to block his entrance to the U.S. Capitol.

America’s Place in the World

Access to open shipping lines was an important struggle in the British and German war. Germany responded to a British blockade by escalating its attacks on shipping vessels, but many Americans viewed these matters as not their concern.

Then came the May 7, 1915 sinking of the RMS Lusitania, which shattered the notion that this new form of warfare could be easily ignored. After being struck by a German torpedo, the luxury cruise ship sank in just 18 minutes, resulting in 1,198 casualties – including 128 Americans.

Despite the tragedy, Wilson continued to practice moderation. He responded to the Lusitania’s sinking by gaining German agreement to limit the scope of their submarine activity. Over time, these included restrictions on what kinds of ships could be targeted and what kind of warnings should be provided.

But as the war escalated in 1916, these negotiated successes unraveled.

The Germans believed they could end the war quickly by taking a more aggressive stance. On Jan. 31, 1917, the German government announced the resumption of fully unrestricted submarine warfare.

Faced with the complete rejection of his primary means of limiting the European conflict, Wilson was also jolted by the public revelation of the Zimmerman telegram, which alleged German military collaboration with Mexico.

Both Freedom and Liberty

It was just weeks after Germany hardened its stance that Wilson strode to the podium and faced Congress.

Wilson addressed the importance of both freedom and liberty, but let his priority be known: “Property can be paid for; the lives of peaceful and innocent people cannot be. The present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind.”

Wilson, one of the last presidents to write all of his own speeches, delivered an argument for going to war that provided a foundation for transforming America’s role in the global order.

Americans had long resisted the temptation to engage in European politics. A broad ocean reinforced the notion that European affairs could be left at a distance.

Wilson’s speech directly addressed this notion the seas would protect Americans. He saw the oceans as conduits of a new era, not a barrier. He expressed disbelief that any civilized nation would reject the rules on submarine warfare, as Germany had, and explained how these commercial routes allowed international cooperation, describing the waterways as “the free highways of the world.”

Wilson was already embracing a more robust international order. He explained that Americans had no quarrel with the German people but only with their government. For Wilson, the German Empire was part of an outdated world order,

“when peoples were nowhere consulted by their rulers and wars were provoked and waged in the interest of dynasties or of little groups of ambitious men who were accustomed to use their fellow men as pawns and tools.”

The use of U-boats as a weapon of terror represented the manner in which autocratic governments threatened their own people and the wider world. Neutrality gave way to defiance. Wilson said: “We will not choose the path of submission.”

Wilson’s proclaimed peace without victory could be reconciled only with a postwar order grounded in liberty, not American dominance. He memorably declared, “The world must be made safe for democracy” and expressed “We desire no conquest, no dominion.”

Wilson’s War

Wilson speech succeeded.

His call for war received acclaim from the daily newspapers, including The New York Times, which printed the entire text of his speech on page one.

More importantly, Congress declared war on Germany on April 6. American neutrality had been replaced by a substantial commitment of troops and resources, the first of which arrived in France that June.

The prominent historian and Wilson biographer John Milton Cooper Jr. described the address as “not only the most important but also the greatest speech of his life.” Wilson had surrendered the desire to remain neutral without giving up on persuading the world to build a more just postwar order.

Wilson’s complex legacy would soon take a tragic turn. His aggressive campaign to lobby for this new peace and his League of Nations left him exhausted. He suffered a massive stroke in 1919 and died in 1924.

Wilson should be remembered for the contradictions. He won reelection for keeping America out of foreign wars and then lead us into one of the century’s bloodiest conflicts. He struggled with popular demands for American isolationism, but helped lay the foundation for the 20th-century vision of American leadership. Today, as leaders on both sides of the Atlantic are struggling to define the relevance of these international partnerships, Wilson’s rhetoric is a powerful legacy.

About the Writer

Gordon Stables, Associate Dean of Student Affairs, Director of Debate & Forensics, & Clinical Professor of Communication, University of Southern California, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Bondi Defends DOJ Handling of Epstein Files in House Testimony

Valley Crime Stoppers’ Most Wanted Person of the Day: Ofelia Pena