Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Fifteen years ago, southeast Fresno, near the border of Sanger, was a jewel in the eye of developers and community leaders. The undeveloped farmland had the potential for not only new homes and retail centers, but it could be transformed into modern, walkable neighborhoods far away from Fresno’s seemingly default northern sprawl, supporters said.

But, with an environmental study nearly complete for what’s referred to as the Southeast Development Area, Fresno officials are putting the plans on hold. They cite a potential billion-dollar infrastructure investment to develop the area. Some have also said the area’s lagging population forecasts don’t justify the outward growth.

“While it may be prudent to consider approval of the environmental and specific plan as part of the long-range, multiple-year planning process — I am not comfortable with implementing any City-led development or capital improvements until population growth thresholds have been sufficiently addressed, and a financial model that allows private development to finance such growth has been identified,” Fresno Mayor Jerry Dyer said.

Fresno City Councilman Luis Chavez disagreed on the population growth, calling SEDA essential to solve Fresno’s high housing costs. But he also says the building industry has failed to present a plan to fund the necessary sewer and water lines to support growth.

A continuing failure to reach an agreement between the city and county on how to divide property taxes further exacerbates the funding challenge. Environmental groups have spoken up against what they call an inadequate environmental impact report for SEDA. In addition, numerous property owners have also vocally opposed urbanization of the rural area.

Meanwhile, builders say the city is running out of developable land and add that it’s too soon to kill the project considering the work that has gone into environmental studies and plans. Developers also say they won’t know those infrastructure cost estimates until they are released to the public.

In addition, they say Clovis and Madera County are growing at rapid rates because of a Fresno housing shortage.

“The Building Industry Association believes that failure to adopt a Specific Plan for SEDA will eventually bring development in the City to a standstill, limit housing opportunities and, thereby, drive up the cost of housing making housing less affordable,” states a letter from the Building Industry Association of Fresno Madera Counties.

Counters attorney Patience Milrod, a land-use expert who represents progressive organizations: “You want to build out here, fine, but you have to figure out how to do it in a way that protects everybody else and that contributes to the city… and doesn’t just take advantage of everybody else and assume the public will pay for the privilege of building.”

Nearly 18 Years in the Making, SEDA Potentially Dead Before a Major Milestone

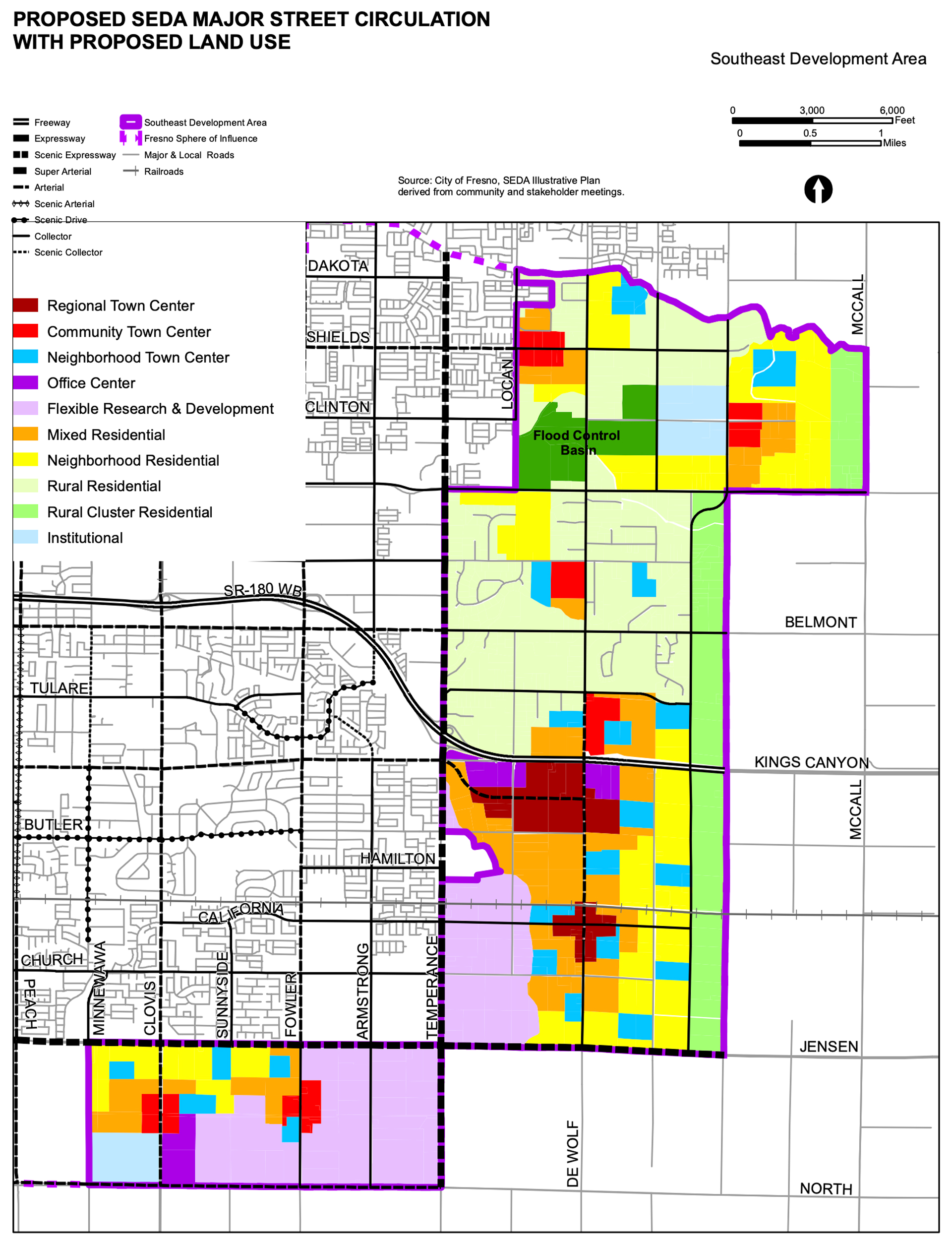

On 9,000 acres spread between Dakota and North avenues and McCall and Minnewawa avenues, planners say as many as 45,000 housing units could be added to Fresno in the next decade it would take to roll out the plan.

Planners envisioned community town centers supporting neighborhoods and public civic spaces and residential areas of different densities. Office space and mixed-use development could provide jobs and services. The city estimated the area could support up to 37,000 jobs.

When the plan was first proposed in 2006 under then-Mayor Alan Autry, it received national awards for its vision and inclusion of transit-oriented concepts. Many community leaders and activist groups praised the plan, saying it was exactly what Fresno needed and that it embraced the planning concepts that the city should have utilized decades before. In addition, southeast Fresno leaders said they welcomed the jobs and investment the plan would bring to their area.

Eighteen years later, it has undergone a name change — SEGA to SEDA — and has yet to move forward. And, before any construction can begin the city has to finish a study on how development would affect the environment. The EIRs look at nearly two dozen factors development could affect, from noise and air pollution to traffic and wildlife impacts. The city used a $625,000 grant from the California Department of Housing and Community Development to pay for the studies.

The city undertook both the EIR and a specific plan — a document outlining how development would look at the street and zoning level — at the same time. That document now needs to go before the Fresno Planning Commission and Fresno City Council before it can be approved.

City, Builders in Disagreement About Order of Operations for Development

Because the new development would replace farmland, the area lacks the streets, water lines, and sewer lines to support an urban population.

Chavez said infrastructure costs could range between $700 million and $1 billion. Other estimates cited in public comments for the EIR have gone as high as $2 billion.

“The lack of engagement from the BIA is just, like, jaw-dropping to me,” Chavez said. “Something so significant and so big, because this plan that we’ve been working on is going to really outline what the city of Fresno’s growth plan looks like for the next quarter century.”

Chavez said the city has made mistakes in the past expanding outward without any plan in place to support those populations.

The city has a few options when it comes to funding infrastructure. It can issue revenue bonds. It can approve special tax districts — called Mello Roos districts — where homeowners agree to added assessment to property taxes.

Chavez said he envisions a hybrid of those two methods.

Without a funding mechanism in place, the city can’t know what the traffic or water demand will be, Chavez said. And the EIR would be inadequate.

“What would be the purpose of approving the EIR if we don’t have the details of what the infrastructure will look like, right?” Chavez said.

SEDA Would Be Phased Approach: Building Industry

Mike Prandini, president of the Building Industry Association of Fresno Madera Counties, said the city hasn’t released the breakdown of the infrastructure cost estimates because the EIR and specific plans aren’t finished.

Prandini said he was told that the figure would be more than a billion dollars, but he was not given the details driving that figure.

“We need to get the specific plan done, completed and the EIR approved for that specific plan and then we can move ahead and look at the infrastructure,” Prandini said. “If it means we can’t do anything for some years, that’s fine. But at least we’ve got the plan approved.”

Builders need to see those numbers to establish a plan. Development for SEDA wouldn’t happen all at once. Roads would be built as new neighborhoods came in. So that billion-dollar estimate may not need funding at the front end, Prandini said.

Getting water from the city’s new wastewater treatment plant will probably have to be done at the outset, Prandini said. The city says a large water line would need to be run from McKinley Avenue to North Avenue. Prandini provided an estimate of $500 million for that project.

“We understand a big number over 30 years, but does everything have to be paid for at once?” Prandini said.

Southeast Fresno’s Population Divided on Growth

A group called the Fresno Southeast Property Owners opposes development there. Members wrote in comments that the plan does not account for growing water demand. Growth also comes at the cost of prime farmland, they say.

Lyle Nelson, president of the group, said in a comment letter on the EIR that many families have been there 50 years and longer. Large numbers of property owners have not been notified about the plans, he said.

“My concern is that many of the property owners who have held their property for 50 years and longer and have done their long-range planning with the intent of passing their homestead, ranch, orchard, or farm onto a family member to continue their planned estates for years to come, have not been treated fairly,” Nelson said.

Fresno County Supervisor Nathan Magsig, whose district includes SEDA, said a lot of residents have shared concerns about how development would affect their property.

“Some were very interested in selling their property, but a lot of them were not,” Magsig said.

Another hurdle for planners would be uniting the city and county to come up with a tax-sharing agreement. Land in SEDA was brought into Fresno’s sphere of influence in the early 2000s, but it is not technically part of the city, yet. The city and the county both have to approve any annexation. Part of that approval includes agreeing on how to share property taxes.

The previous 62/38 split (62% to the county, 38% to the city) expired in October 2020. Fresno leaders have said they want a 50/50 split, as was historically done. Magsig said Fresno’s outsized demand for county services, such as social services, behavioral health, and more, prevents a 50/50 split.

Chavez said undeveloped land brings nothing to the county coffers and SEDA would net the county significant funding.

Will Fresno Residents Be Interested in What Builders Have to Offer?

Patience Milrod, an attorney for the Central Valley Industrial Areas Foundation, the Fresno Madera Tulare and Kings Counties Central Labor Council, and Regenerate California Innovation organizations, called the de facto decision to delay approving environmental documents “rational.”

Milrod and her organizations track housing issues in Fresno and Clovis.

“What they’re looking at is a level of expenditure that would cripple the city’s efforts to foster infill development of all kinds, commercial, retail, residential, in favor of a project that might never happen because it’s unlikely that there’s going to be an adequate population increase to provide buyers for all those above-market homes,” Milrod said.

Long-range estimates show Fresno’s population growth outpacing that of California’s — 20-year forecasts showing 7.16% for Fresno compared to the state’s 2.99% growth.

However, a study commissioned by the Greenfield Coalition, of which Milrod is a member, showed population growth will be from people making less than the area median income. Milrod said in a response to the EIR that demand for housing would occur in the affordable sector, not market-rate housing.

The SEDA specific plan said adding additional housing would lower housing costs. The plan also does not limit zoning to single-family. Milrod said smart growth can occur in the area.

She previously supported plans to grow in southeast Fresno, but she said the current plan does not account for a multitude of concerns, both environmental and financial.