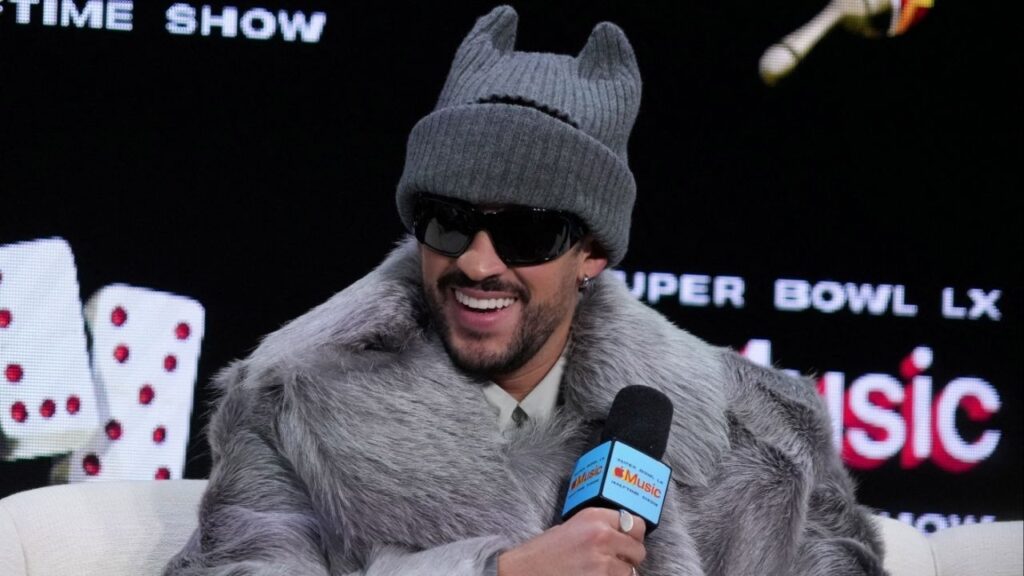

Bad Bunny performs at Madison Square Garden in New York, April 27, 2019. Amid harsh rhetoric from the White House, the Puerto Rican superstar will take the stage on Sunday, promising a message of unity: “The world will dance.” (Chad Batka/The New York Times/File)

- The Super Bowl has never had a halftime performer — or a controversy — quite like Bad Bunny.

- The Latin superstar, who conquered global streaming with nostalgic sounds from his native Puerto Rico, is set to make history Sunday.

- Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl appearance has become a political flashpoint amid the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Super Bowl has never had a halftime performer — or a controversy — quite like Bad Bunny.

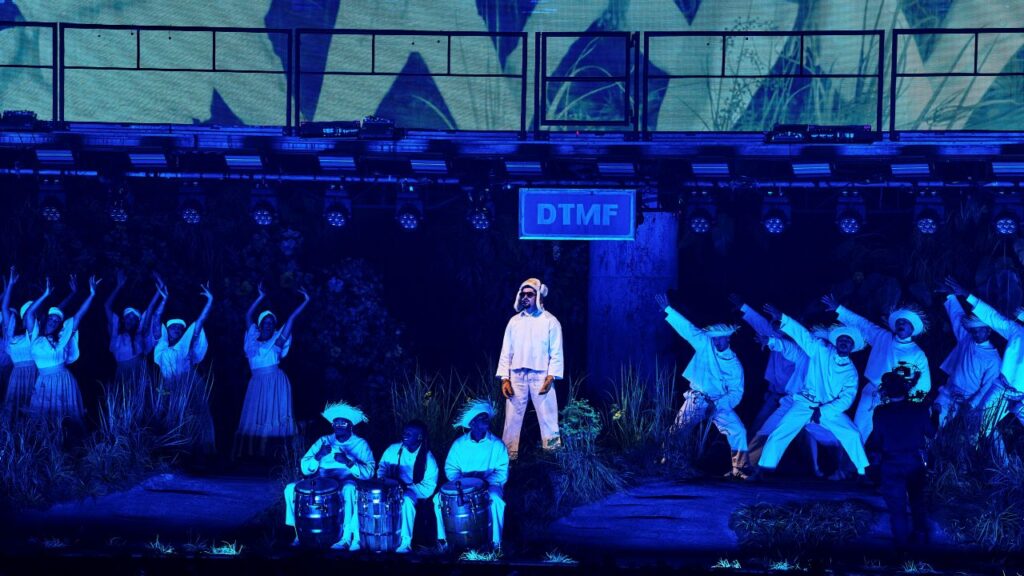

The Latin superstar, who conquered global streaming with reggaeton earworms seasoned with nostalgic sounds from his native Puerto Rico, is set to make history Sunday, giving the first all-Spanish performance in the game’s 60-year history. It will be the capstone achievement for a transformational figure in Latin pop, who has broken ticketing records around the world, racked up 15 Top 10 hits and Sunday took album of the year at the Grammys in another milestone for Latin music.

Yet before he has sung a note, Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl appearance has become a political flashpoint amid the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown and the fears it has stirred among Latino communities in the United States, immigrant or not. When the NFL announced him as its halftime headliner in September, sports and media observers saw a shrewd move by a league seeking to expand its global footprint. But the White House and right-wing media convulsed in condemnation.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said that Immigration and Customs Enforcement would “be all over” the game, to be held at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California. Conservative commentator Tomi Lahren dismissed Bad Bunny as “not an American artist.” (Puerto Rico is, of course, a U.S. territory.) In a recent interview, President Donald Trump said he would not attend the game, calling Bad Bunny’s selection “a terrible choice” and saying that “all it does is sow hatred.”

Turning Point USA’s Counter Halftime Show

Turning Point USA, the conservative organization founded by Charlie Kirk, said it would present its own counterprogramming, a “one-of-a-kind streaming event” called the All-American Halftime Show that will feature Kid Rock and country singers Brantley Gilbert, Lee Brice and Gabby Barrett. “We’re taking the American Culture War to the MAIN STAGE,” the organization said on its website last month, adding: “No ‘woke’ garbage. Just TRUTH. Just FREEDOM. Just AMERICA.”

Bad Bunny said last year that he would avoid touring in U.S. venues out of concern that immigration agents might target his fans. But since being announced for the Super Bowl, his message has been more about joy and solidarity than fear. In a trailer for the game released last month, he grooves to his tender, salsa-flavored hit “Baile Inolvidable” (“Unforgettable Dance”) with partners of various ages, genders and ethnicities, beneath the brilliant, fire-red leaves of a Flamboyant tree, a symbol of Puerto Rico and the Caribbean. “The world will dance,” a title card reads.

In an acceptance speech at the Grammys, Bad Bunny also indicated he would not back down. “Before I say thanks to God, I’m going to say ‘ICE out,’” he said. “We’re not savage, we’re not animals, we’re not aliens. We are humans, and we are Americans.”

With blood spilled on the streets of Minneapolis in recent weeks during demonstrations opposing the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement plan, Bad Bunny’s appearance at the Super Bowl has taken on a particular kind of urgency, and he need not make any explicit protest to get his message across.

“We are in this time of anti-immigrant rhetoric, and Latinos and Latin American immigrants in particular have borne the brunt of a lot of his hatred,” said Petra Rivera-Rideau, an American studies professor at Wellesley College and the co-author of a recent book about Bad Bunny’s global rise.

“Even Bad Bunny’s presence there,” Rivera-Rideau added, “because of this political context, is a statement.”

Origins of Bad Bunny

The performer born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio 31 years ago took his stage name in memory of the unwanted rabbit costume he was made to wear as a child for an Easter party.

He began his recording career in 2016, and quickly made a mark in reggaeton and hip-hop as a guest star — with Drake, Cardi B, Daddy Yankee — so that by the time he released his debut album, “X 100PRE,” in 2018, he was indispensable. In 2020, he made his first Super Bowl appearance as a guest of the show’s headliners, Jennifer Lopez and Shakira. In a striking comment on migrant family separations during the first Trump administration, their show featured children in cages; Lopez wore a Vegas-ready feathered cape that flipped from an American flag to the Puerto Rican one.

Bad Bunny’s early rise dovetailed with the popularity of Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee’s song “Despacito,” which exploded — thanks in part to a remix with English-language contributions by Justin Bieber — and demonstrated how Latin pop could thrive in the borderless domain of YouTube and streaming platforms.

For years, performing in English was the crossover toll that Latin stars — whether Ricky Martin or Shakira — had no choice but to pay, largely to make themselves palatable to American radio. Using streaming as his bypass lane, and sticking to Spanish, Bad Bunny has been a phenomenon, becoming Spotify’s top global artist in four of the last six years. He rode that fame to roles in Hollywood films like “Bullet Train” and “Caught Stealing.” Along the way came other marks of peak celebrity, like dating Kendall Jenner (and promoting Gucci products with her).

Bad Bunny Draws on His Roots

At the same time, Bad Bunny’s music increasingly turned to Puerto Rico in ways both explicit and subtle, like dotting his lyrics with idiosyncratic local slang. At the Met Gala last year, he wore a custom version of the pava, Puerto Rico’s country straw hat. His latest album, “Debí Tirar Más Fotos,” completes that trajectory, mixing traditional Puerto Rican rhythms and musical forms, like bomba and plena, with booming trap beats.

“He’s shifted the center of gravity in global pop without disconnecting from where he comes from,” said Sulinna Ong, Spotify’s global head of editorial.

Keeping a focus on Puerto Rican social issues, like gentrification and failures of governance, has also made Bad Bunny the island’s most recognizable advocate. The music video for his 2022 song “El Apagón,” about the island’s frequent power blackouts, included an 18-minute documentary about those issues. The unofficial mascot of his “Debí Tirar Más Fotos” era is the sapo concho, the Puerto Rican crested toad, which has become endangered by overdevelopment.

When it came time to tour “Debí Tirar Más Fotos,” Bad Bunny avoided the continental United States as the Trump administration ramped up immigration operations and deportations — reflecting a fear that has spread through the Latin music business since Trump took office again. “ICE could be outside” one of the concert venues, he told I-D magazine in September. “It’s something we were talking about and very concerned about.”

31 Date Residency in Puerto Rico

Instead, he played a 31-date residency in Puerto Rico — called No Me Quiero Ir de Aquí (I Don’t Want to Leave Here) — that lifted the local economy. As part of its stage design, it featured a pink and yellow casita: a humble house with a porch, a symbol of everyday Puerto Rican life — though for Bad Bunny’s shows it became a hybrid VIP section, where celebrities like LeBron James and Penélope Cruz hung out.

Days after Bad Bunny completed the residency, he was announced as the halftime show headliner. The game’s opening ceremony will also feature Green Day, the veteran punk band, which for years has been tweaking old lyrics in protest of Trump and his allies like Elon Musk. When The New York Post asked the president last month about the performers, he said, “I’m anti-them.”

Benjamín Torres Gotay, a columnist at Puerto Rican newspaper El Nuevo Día, said that when it came to the Super Bowl, “people in Puerto Rico understand that this is not only a pop artist being chosen because he’s famous.”

“Most of us understand that this has a political dimension,” Torres Gotay added, “in the sense that there is all this debate about: What is America? What is the role of immigrants, of Latin American people or nonwhite people in U.S. society?”

A Victory for Jay-Z

Bad Bunny’s appearance is also a win for Jay-Z, who has booked the talent for each halftime show since 2020 with Roc Nation, his entertainment company.

When Roc Nation made its deal with the NFL in 2019, the league was facing a crisis over the apparent blackballing of Colin Kaepernick, the quarterback who had knelt during the national anthem as a protest against racism and police brutality. Some Black artists had turned down offers to play the halftime show, which regularly draws more than 100 million viewers.

Jay-Z took no small amount of heat for agreeing to work with the NFL, but he argued that he could help make it “all-inclusive,” and said the league was committed to social justice initiatives. “We’ve moved past kneeling,” he said. Roc Nation’s halftime shows have indeed been a smashing, zeitgeisty success, with Rihanna, a hip-hop revue led by Dr. Dre and last year’s triumphal appearance by Kendrick Lamar.

The choice of Bad Bunny also aligns with the goals of the NFL, which has been gradually expanding internationally, including to Latin America — where a Bad Bunny appearance would function as ideal marketing. Hans Schafer, a Live Nation executive who has worked extensively with Bad Bunny, called the Super Bowl appearance a symbolic “cultural handoff.”

“For decades, the Super Bowl halftime was sort of the final boss of Anglo pop,” Schafer added. “This signals more a global culture that has officially shifted. Bad Bunny represents what the world is actually listening to.”

To fully understand the significance, Schafer suggested a shift in perspective. “We talk about, ‘What does it mean for Bad Bunny to be on the Super Bowl?’” he said. “I think it’s much more interesting to frame the question as, ‘What does that mean for the Super Bowl to have Bad Bunny?’ ”

Kristi Noem: Super Bowl Is for Americans Only

The political reaction to Bad Bunny, however, may be a sign that a big portion of the Super Bowl’s traditional audience is not interested in sharing the game with the rest of the world. For many Americans, the Super Bowl is an ultrapatriotic event, almost sacred in its rituals, and its monocultural big-tent status has survived even in a fractured era.

“I think people should not be coming to the Super Bowl unless they are law-abiding Americans who love this country,” Noem told conservative podcaster Benny Johnson, in the same interview where she confirmed that ICE agents would be at the stadium, a statement she has not taken back. (Although federal agents are often sent to major sporting events, including the Super Bowl, the NFL’s security chief said this past week she was confident there would be no “immigration enforcement operations” at the game Sunday.)

In 1968, José Feliciano, who was born in Puerto Rico, played a distinctive version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” — respectfully, but with liberties — at a World Series game, and there was a strong negative reaction, with at least one fan quoted at the time as calling it “a disgrace, an insult.” At the Major League Baseball All-Star Game in 2013, Marc Anthony, who was born in New York to Puerto Rican parents, sang a soaring “God Bless America”; Twitter exploded with racist insults.

Bad Bunny will not be singing the national anthem — that’s Charlie Puth — but his performance may still be seen as happening dangerously close to an All-American totem.

Desiree Perez, the CEO of Roc Nation, did not respond to questions about the political controversy over Bad Bunny’s announcement. But she hailed him as an ideal choice for the moment.

“Bad Bunny is a global phenomenon whose cultural impact transcends music,” Perez said. “This will be a celebration, with a world audience on its feet.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Ben Sisario/Chad Batka/Amy Lombard

c.2026 The New York Times Company