Posters in the style of street artist Banksy, inspired by the man who was indicted for throwing a sub sandwich at a federal agent, cover a building’s wall near Gallaudet University in Washington, Aug. 17, 2025. In what could be read as a citizens’ revolt, ordinary people serving on grand juries have repeatedly refused in recent days to indict fellow residents who became entangled in the Trump Administration’s immigration crackdowns and other shows of force. (Eric Lee/The New York Times/File)

- D.C.'s grand jury failures lead to tensions between federal judges and Jeanine Pirro, the former Fox News co-host who took over the U.S. attorney’s office.

- In an apparent citizens’ revolt, people on grand juries have repeatedly refused in recent days to indict their fellow D.C. residents.

- “My guess is that these grand jurors are seeing prosecutorial overreach, and they don’t want to be part of it,” says Barbara L. McQuade, a former U.S. attorney in Detroit.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In the three weeks since President Donald Trump flooded the streets of Washington with hundreds of troops and federal agents, there have been only a few scattered protests and scarcely a word from Congress, which has quietly gone along with the deployment.

But one show of resistance has come from an extraordinary source: federal grand jurors.

In what could be read as a citizens’ revolt, ordinary people serving on grand juries have repeatedly refused in recent days to indict their fellow residents who became entangled in either the president’s immigration crackdown or his more recent show of force. It has happened in at least seven cases — including three times for the same defendant.

Given the secretive nature of grand juries, it is all but impossible to know precisely why this has been happening, but the persistent rejections suggest that grand jurors may have had enough of prosecutors seeking harsh charges in a highly politicized environment.

Rare for Grand Juries to Reject Indictments

Courthouse wits have long quoted Judge Sol Wachtler, the former New York jurist who said that prosecutors are in such complete control of grand juries that they could get them to indict a ham sandwich. But that old saw did not hold true in the rebellion in U.S. District Court in Washington, where grand jurors seem to have taken a stand in defense of their community.

“First of all, it is exceedingly rare for any grand jury to reject a proposed indictment because ordinarily, prosecutors use discretion in only bringing cases that are strong and advance the interests of justice,” said Barbara L. McQuade, a former U.S. attorney in Detroit who teaches at the University of Michigan Law School. “I have seen this maybe once or twice in my career of 20 years, but this is something different.

“My guess,” McQuade went on, “is that these grand jurors are seeing prosecutorial overreach, and they don’t want to be part of it.”

While crime has fallen in Washington since National Guard troops and federal agents started to police the streets in large numbers in mid-August, the deployment has chafed many local residents, who have found their presence to be a source of anxiety, not security. And because of the deployment, a flurry of defendants have been charged with federal felonies in cases that would typically have been handled at the local court level, if they were brought at all.

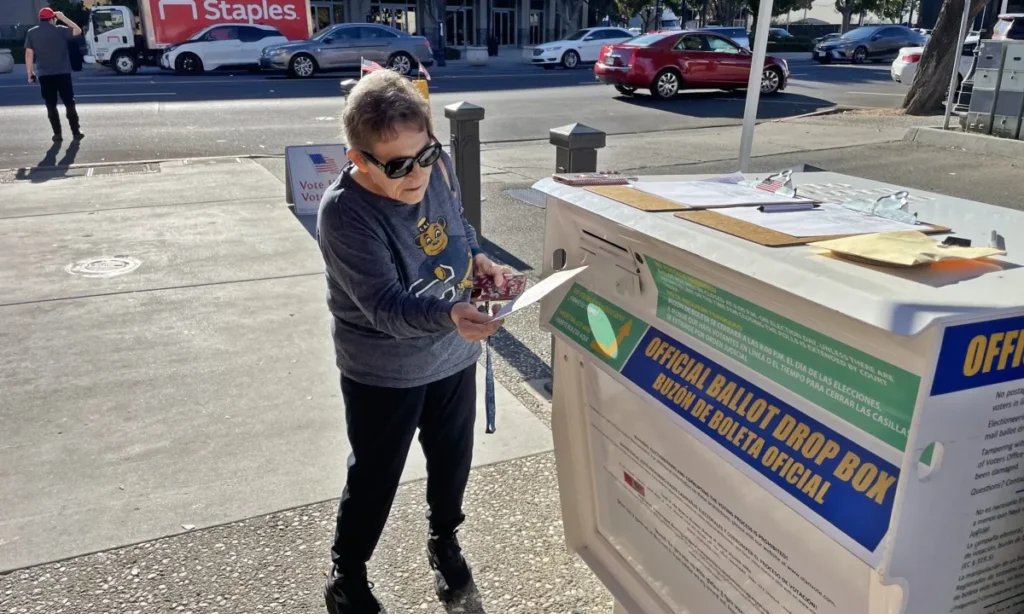

Many of these cases have recently been downgraded or dismissed altogether after failing in grand juries, a tacit acknowledgment by the U.S. attorney’s office in Washington that they were overcharged to begin with. The most prominent example is the case of Sean C. Dunn, a former Justice Department paralegal who was charged with felony assault after he threw a sub-style salami sandwich at a federal agent on patrol near the corner of 14th and U streets. His charges were knocked down to a misdemeanor at the end of August after prosecutors were unable to indict him.

Cases Crash and Burn Out of the Public’s Eye

While Dunn’s case has become a cause celebre, inspiring Banksy-style images of figures hurling hoagies on walls across the city, other cases have also crashed and burned, without as much publicity.

On Friday, for example, about a week after failing to obtain an indictment, prosecutors dismissed a case against Nathalie Rose Jones, an Indiana woman who had been arrested on felony charges of threatening to kill Trump on social media.

Jones, who has been described by friends as being mentally ill, was taken into custody Aug. 16 after she attended a march outside the White House. Secret Service agents, who had seen her posts calling Trump a Nazi and saying that she wanted to disembowel him, had interviewed her twice before the protest but did not initially seek to detain her.

On Thursday, prosecutors had moved to dismiss another threat case after it, too, failed in the grand jury. This one had been brought against Edward Alexander Dana, a self-described “person with intellectual disabilities” who was arrested Aug. 21, also on charges of having threatened to kill Trump.

The decision to dismiss the case in federal court and refile it as a misdemeanor in the lower Superior Court came after videos emerged of Dana telling a police officer in a slurring voice that he had drunk “seven alcoholic beverages” that night, court papers say. Another video, the papers assert, showed Dana at the police station “cordially thanking the officers and lying on the floor, singing and yelling non sequitur, incomprehensible statements.”

These grand jury refusals to indict, while remarkable on their own, point to a broader breakdown in the bonds of trust that judges have traditionally afforded to government lawyers when they show up in court.

The erosion of this trust — known in legal parlance as the presumption of regularity — has been widespread in the many civil cases challenging Trump’s political agenda, where judges have repeatedly accused Justice Department lawyers of misleading them or violating their orders.

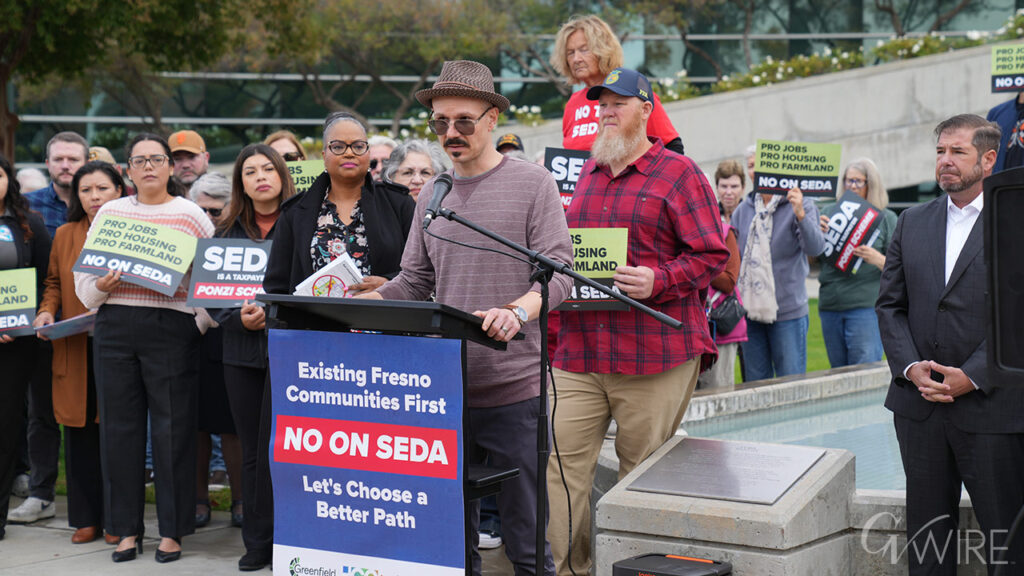

But now the phenomenon has started to crop up in criminal cases, too. It first occurred in July in Los Angeles, where prosecutors struggled to obtain indictments against several protesters arrested at demonstrations against federal immigration actions.

Pirro Takes to Fox to Air Concerns

In Washington, the grand jury failures have led to tensions between some federal judges and Jeanine Pirro, the tough-talking, gravel-voiced former Fox News co-host who took over the U.S. attorney’s office in May.

Pirro has not taken kindly to news reports about her office’s challenges with grand juries. Appearing on “Fox News Sunday” on Aug. 31 after prosecutors failed to indict Dunn, she went on to complain about the city’s grand jurors. Many of them, she surmised, “live in Georgetown or in Northwest or in some of these better areas” where, as she put it, “they don’t see the reality of crime.”

“The fact that they’re so used to crime,” Pirro went on, “that crime is so normalized in D.C., that they don’t even care about whether or not the law is violated is the very essence of what my problem is in D.C.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Alan Feuer/Eric Lee/Haiyun Jiang

c.2025 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories