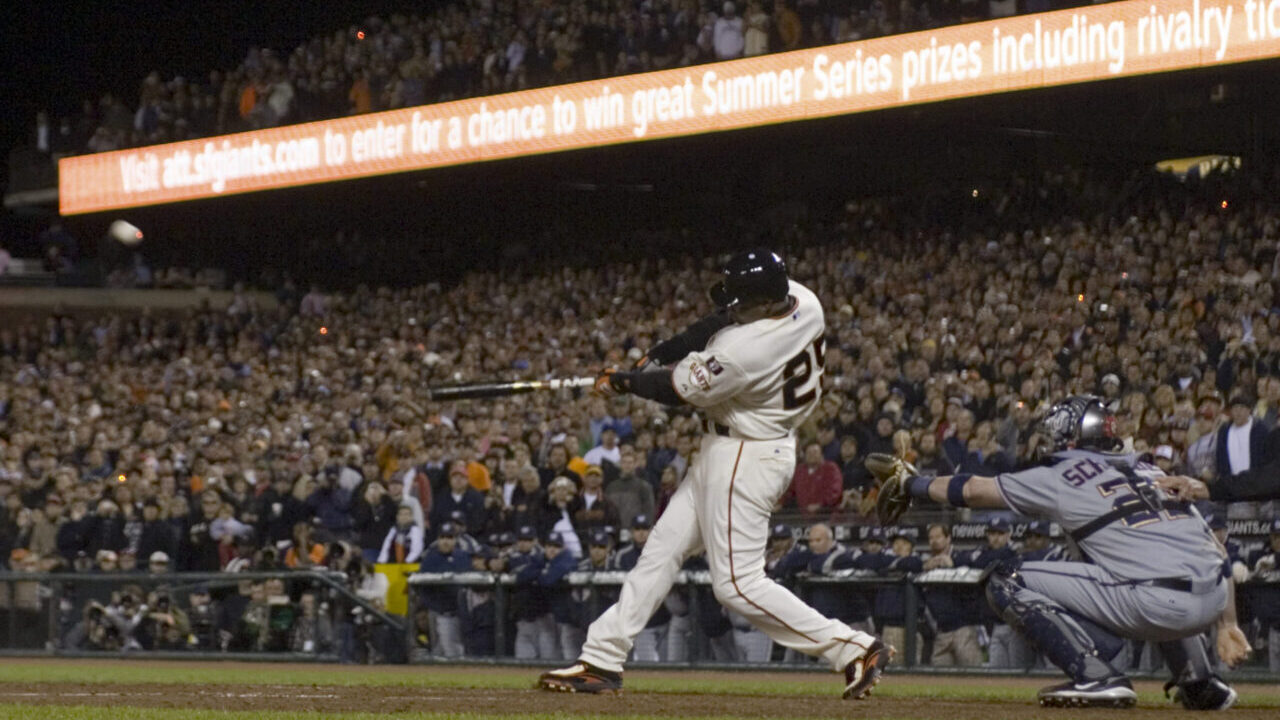

The San Francisco Giants’ Barry Bonds hits his 756th all-time career home run, breaking Hank Aaron’s record, in San Francisco, Aug. 7, 2007. (Peter DaSilva/The New York Times/File)

- Baseball's "Greatest of All Time" title no longer belongs to New York Yankees legend Babe Ruth but to Barry Bonds.

- A statistical analysis ranks Roger Clemens second, Willie Mays third, Ruth fourth, and Henry Aaron fifth.

- The new rankings skew toward players in the post-segregation era because the talent pool greatly expanded.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Every sport has its arguments over which player was the greatest, but no sport takes the debate as seriously as baseball does. It is a game informed by an obsession with statistics, such that passions are often checked by numbers: How could anyone love a player with such a miserable on-base percentage?

It is something consequential, then, when anyone makes a declarative statement regarding anything about baseball. But a team of statisticians did just that. They have spent years devising a definitive ranking of baseball’s best performers, no matter what era or which team was involved. Their new method compared players across history by placing the respective achievements within the context of a given year’s pool of eligible baseball talent.

The controversial answer: The “Greatest of All Time” title no longer belongs to New York Yankees legend Babe Ruth but to Barry Bonds.

The poor Bambino isn’t even second. That spot belongs to Roger Clemens, who pitched for both the Boston Red Sox and the Yankees. He is followed by Bonds’ godfather, Willie Mays (both men are generally associated with the San Francisco Giants, though they played for other teams as well). Ruth ranks fourth, followed by Hank Aaron of the Milwaukee, and later Atlanta, Braves. Mickey Mantle, who won seven World Series rings while wearing Yankee pinstripes, falls to 23rd.

Baseball purists may object, noting that Bonds and Clemens are among several high-profile major league players accused of using steroids during the 1990s. (This likely explains why neither player is enshrined in Cooperstown, the sport’s Hall of Fame in upstate New York.)

The Stats Tell the Story

But statistics tell their own story. Daniel J. Eck, a statistician at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who led the new study and has been working on the model for about a decade, noted that because so many other players took performance-enhancing drugs, or PEDs, any improvement from banned chemicals is reflected in players’ achievement models for those years. “I’m OK with a PED-laden person being No. 1, over, say, a person who played before baseball was integrated,” Eck said. In other words, despite Bonds’ steroid use, he put up more outlandishly impressive numbers, in era-adjusted terms, than Ruth.

Needless to say, trying to calculate the size of the baseball talent pool in an entire society, not just those who ended up in Major League Baseball, requires an enormous amount of historical data, as well as many carefully considered assumptions. But several experts in baseball statistics, or sabermetrics, said the new ranking methodology, devised by statisticians at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and published recently in the Annals of Applied Statistics, was a home run.

“It’s arguably the state of the art, at this point, for player evaluation over time,” said Dr. Michael J. Schell, an oncologist and biostatistician at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Florida, who also writes about baseball. Some years ago, as an outside expert, he reviewed a draft of the Illinois team’s work and found its calculations less than fully persuasive. That was no longer the case. “They’ve moved the ball forward,” Schell said.

Eck said he knew of no other serious ranking system that had Bonds in first place.

As its starting point, the Illinois analysis used a well-established measure known as Wins Above Replacement. Whether a player is a designated hitter, a skilled shortstop or a closer with a blistering fastball, his WAR indicates how many wins he contributed to his team in a given year relative to a generic player.

Stats Before and After Jackie Robinson

But the researchers wanted to know how each player’s achievements stacked up against all of the latent talent available to the sport of baseball that year, an immense undertaking that involved accounting for racism, demography, war and the rise of both basketball and football. “The statistical model we developed is entirely new, not just a tweak of existing ideas,” Eck said.

Eck linked the distribution of talent to the distribution of achievement, allowing for a comparison between the two that works as well for a player in 1925 as it does for one in 2025. “To have a high talent score, one must stand out from their peers in their own time and be a product of a large talent pool,” the study notes.

The new rankings skew toward players in the post-segregation era because the talent pool greatly expanded after Jackie Robinson broke the racial barrier by joining the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. This statistical rebalancing has led to accusations that the Illinois model tried to leave segregation-era standouts such as Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby out of the record books.

“They’re not junk,” Schell said of those players, although he allowed that they may have previously been “overrated,” having played at a time when the talent pool was small and relatively unimpressive. (Training and nutrition also improved.) Still, no study can (yet) measure the emotional appeal of one player over another.

Christopher Kinson, one of the statisticians who worked on the new model, has been pained by charges that he and his colleagues were trying to engineer outcomes. “We didn’t set out to do this because we believe that the great players are not white,” he said. White players continue to dominate the 25-player list, which does not include recent stars like the Japan-born wunderkind Shohei Ohtani, a Los Angeles Dodger.

“The people who are writing this paper are very sophisticated statistically, very sophisticated mathematically,” said Gregory J. Matthews, a statistician at Loyola University Chicago who also consults for the Cincinnati Reds. “It’s a very rigorous, well-written study.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Alexander Nazaryan/Peter DaSilva)

c.2025 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

The Coming Trump Crackup