Share

Marine Corps veteran Ron Winters clearly recalls his doctor’s sobering assessment of his bladder cancer diagnosis in August 2022.

Lauren Sausser

KFF Health News

“This is bad,” the 66-year-old Durant, Oklahoma, resident remembered his urologist saying. Winters braced for the fight of his life.

Little did he anticipate, however, that he wouldn’t be waging war only against cancer. He also was up against the Department of Veterans Affairs, which Winters blames for dragging its feet and setting up obstacles that have delayed his treatments.

Winters didn’t undergo cancer treatment at a VA facility. Instead, he sought care from a specialist through the Veterans Health Administration’s Community Care Program, established in 2018 to enhance veterans’ choices and reduce their wait times. But he said the prior authorization process was a prolonged nightmare.

“For them to take weeks — up to months — to provide an authorization is ridiculous,” Winters said. “It doesn’t matter if it’s cancer or not.”

After his initial diagnosis, Winters said, he waited four weeks for the VA to approve the procedure that allowed his urologic oncologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas to remove some of the cancer. Then, when he finished chemotherapy in March, he was forced to wait another month while the VA considered approving surgery to remove his bladder. Even routine imaging scans that Winters needs every 90 days to track progress require preapproval.

In a written response, VA press secretary Terrence Hayes acknowledged that a “delay in care is never acceptable.” After KFF Health News inquired about Winters’ case, the VA began working with him to get his ongoing care authorized.

“We will also urgently review this matter and take steps to ensure that it does not happen again,” Hayes told KFF Health News.

Prior authorization isn’t unique to the VA. Most private and federal health insurance programs require patients to secure preapprovals for certain treatments, tests, or prescription medications. The process is intended to reduce spending and avoid unnecessary, ineffective, or duplicative care, although the degree to which companies and agencies set these rules varies.

Insurers argue prior authorization makes the U.S. health care system more efficient by cutting waste — theoretically a win for patients who may be harmed by excessive or futile treatment. But critics say prior authorization has become a tool that insurers use to restrict or delay expensive care. It’s an especially alarming issue for people diagnosed with cancer, for whom prompt treatment can mean the difference between life and death.

“I’m interested in value and affordability,” said Fumiko Chino, a member of the Affordability Working Group for the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. But the way prior authorization is used now allows insurers to implement “denial by delay,” she said.

Cancer is one of the most expensive categories of disease to treat in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And, in 2019, patients spent more than $16 billion out-of-pocket on their cancer treatment, a report by the National Cancer Institute found.

To make matters worse, many cancer patients have had oncology care delayed because of prior authorization hurdles, with some facing delays of more than two weeks, according to research Chino and colleagues published in JAMA in October. Another recent study found that major insurers issued “unnecessary” initial denials in response to imaging requests, most often in endocrine and gastrointestinal cancer cases.

The federal government is weighing new rules designed to improve prior authorization for millions of people covered by Medicare, Medicaid, and federal marketplace plans. The reforms, if implemented, would shorten the period insurers are permitted to consider prior authorization requests and would also require companies to provide more information when they issue a denial.

In the meantime, patients — many of whom are facing the worst diagnosis of their lives — must navigate a system marked by roadblocks, red tape, and appeals.

“This is cruel and unusual,” said Chino, a radiation oncologist. A two-week delay could be deadly, and that it continues to happen is “unconscionable,” she said.

Chino’s research has also shown that prior authorization is directly related to increased anxiety among cancer patients, eroding their trust in the health care system and wasting both the provider’s and the patient’s time.

Leslie Fisk, 62, of New Smyrna Beach, Florida, was diagnosed in 2021 with lung and brain cancer. After seven rounds of chemotherapy last year, her insurance company denied radiation treatment recommended by her doctors, deeming it medically unnecessary.

“I remember losing my mind. I need this radiation for my lungs,” Fisk said. After fighting Florida Health Care Plans’ denial “tooth and nail,” Fisk said, the insurance company relented. The insurer did not respond to requests for comment.

Fisk called the whole process “horribly traumatic.”

“You have to navigate the most complicated system on the planet,” she said. “If you’re just sitting there waiting for them to take care of you, they won’t.”

A new KFF report found that patients who are covered by Medicaid appear to be particularly impacted by prior authorization, regardless of their health concerns. About 1 in 5 adults on Medicaid reported that their insurer had denied or delayed prior approval for a treatment, service, visit, or drug — double the rate of adults with Medicare.

“Consumers with prior authorization problems tend to face other insurance problems,” such as trouble finding an in-network provider or reaching the limit on covered services, the report noted. They are also “far more likely to experience serious health and financial consequences compared to people whose problems did not involve prior authorization.”

In some cases, patients are pushing back.

In November, USA Today reported that Cigna admitted to making an error when it denied coverage to a 47-year-old Tennessee woman as she prepared to undergo a double-lung transplant to treat lung cancer. In Michigan, a former health insurance executive told ProPublica that the company had “crossed the line” in denying treatment for a man with lymphoma. And Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Louisiana “met its match” when the company denied a Texas trial lawyer’s cancer treatment, ProPublica reported in November.

Countless others have turned to social media to shame their health insurance companies into approving prior authorization requests. Legislation has been introduced in at least 30 states — from California to North Carolina — to address the problem.

Back in Oklahoma, Ron Winters is still fighting. According to his wife, Teresa, the surgeon said if Ron could have undergone his operation sooner, they might have avoided removing his bladder.

In many ways, his story echoes the national VA scandal from nearly a decade ago, in which veterans across the country were languishing — some even dying — as they waited for care.

In 2014, for example, CNN reported on veteran Thomas Breen, who was kept waiting for months to be seen by a doctor at the VA in Phoenix. He died of stage 4 bladder cancer before the appointment was scheduled.

Winters’ cancer has spread to his lungs. His diagnosis has advanced to stage 4.

“Really, nothing has changed,” Teresa Winters said. “The VA’s processes are still broken.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

RELATED TOPICS:

Dodgers’ Mookie Betts Out With Broken Toe After Late-Night Bedroom Mishap

15 hours ago

California Gubernatorial Candidate Steve Hilton Vows to Repeal Transgender Athlete Law

19 hours ago

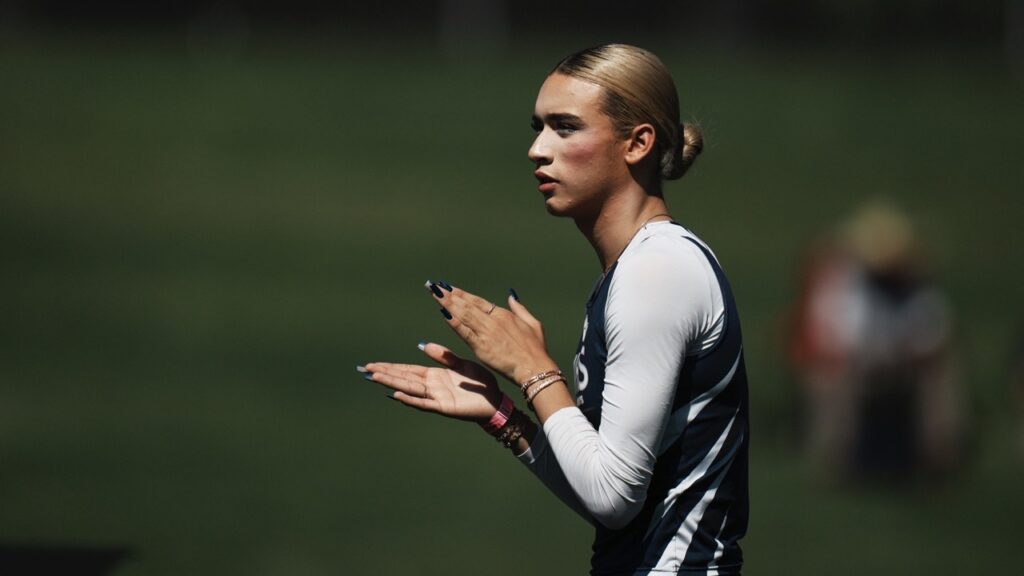

Trans Athlete Competes in California Championships in Clovis Despite National Controversy

22 hours ago

Tim Walz Urges Democrats to Fight Back Harder Against ‘Bully’ Trump

23 hours ago

No. 15 Overall Seed UCLA Eases Past Fresno State Behind a Season-High 22 Hits

23 hours ago

Judge and Ohtani Light Up the First Inning With Historic Homers in Yankees-Dodgers Rematch

23 hours ago

Chapman Homers, Harrison Pitches Five Scoreless Innings as Giants Beat Marlins

23 hours ago

General Is a Good Boy — in English and Spanish

1 day ago

Cabrera, Three Relievers Combine to Lead Marlins to Win Over Giants

Spike in Steel Tariffs Could Imperil Trump Promise of Lower Grocery Prices

Dodgers’ Mookie Betts Out With Broken Toe After Late-Night Bedroom Mishap

California Gubernatorial Candidate Steve Hilton Vows to Repeal Transgender Athlete Law

Trans Athlete Competes in California Championships in Clovis Despite National Controversy

Tim Walz Urges Democrats to Fight Back Harder Against ‘Bully’ Trump