Share

It’s hard to believe now with Fresno State virtually begging fans to show up to games, but there was a time — before Jerry Tarkanian — when Bulldogs basketball was the hottest ticket in town.

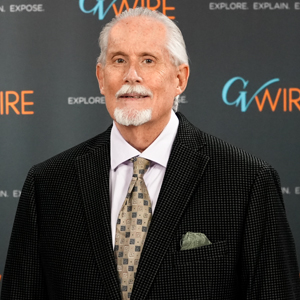

Bill McEwen

Opinion

Not just among sports fans, either. Everybody who was anybody wanted to be there. To be seen, to yell, to make the noise meter in the upper reaches of Selland Arena reach ear-splitting levels.

Boyd Grant, who died Monday on his 87th birthday in a Salt Lake City hospital following a stroke, was responsible for that.

Grant Engineered an Instant Turnaround

The native Idahoan made college basketball matter in Fresno upon arriving in 1977. He took a 7-20 team, added JC recruit Art Williams, and the Bulldogs won 21 games.

Before long, once empty 6,500-seat Selland Arena — newly nicknamed Grant’s Tomb — was too small. The team’s prospects were debated in coffee shops, store aisles, and on talk shows. And fans swore that their coach was a dead ringer for actor George C. Scott.

Now Fresno dared to dream that its Bulldogs could take on the mightiest college basketball powers and win.

Which they did. More than their fair share of the time.

Grant led the Bulldogs to a 194-74 record in nine seasons, three regular-season conference titles, three conference tournament titles, three NCAA Tournament appearances, and the 1983 NIT championship.

“Tiny” — that’s what folks in Idaho and Colorado called him — accomplished something Tarkanian never did as a Fresno State coach: reach the Sweet 16 of the NCAA Tournament.

The year was 1982, and the Bulldogs were the best team on the West Coast. Anchored by Rod Higgins, they finished 27-3 and ranked No. 11 in the country despite not starting a player over 6-foot-8; their season finally ended by Georgetown and Patrick Ewing.

Toughness and Defense Were Grant’s Calling Cards

A year later, a similarly undersized team featuring “Bookend Forwards” Bernard Thompson and Ron Anderson blitzed the NIT field, knocking off UTEP, Michigan State, Oregon State, Wake Forest, and DePaul.

While smoking a cigarette in the tunnel at Madison Square Garden during the NIT Final Four, North Carolina coach Dean Smith told me those Bulldogs were perhaps “the best little team” he had ever seen.

When the tired squad returned to Fresno the afternoon after winning the title — and celebrating until dawn in New York City— thousands of fans greeted them outside the airport and an impromptu parade followed.

Even when they didn’t win, Grant’s Bulldogs left opponents exhausted and bruised. Grant demanded toughness and endurance in his players — traits instilled in him by his college coach, Jimmy Williams, at Snow College and Colorado State. Not only did Grant slightly resemble Scott, but he coached like the man the actor portrayed: Gen. George S. Patton.

Grant stressed the game’s fundamentals, so much so that players weren’t allowed to dribble the first week of fall practice. The squeak of basketball shoes filled the gym, as players learned to get in the proper crouch to play “Boyd Grant defense.”

The Chicago Connection

Early on, Grant’s teams held the ball at the offensive end — waiting for a wide-open shot or a backdoor layup. Keeping the score low and the game tight was the coach’s way of making up for a talent deficit. Run-and-gun UC Irvine coach Billy Mulligan famously called it “vomit basketball.”

But with assistant coach Jim Thrash mining Chicago for recruits Higgins, Tyrone Bradley, Mitch Arnold, and Anderson, the Bulldogs eventually didn’t have to milk the clock. And, when the 3-point shot came into the college game, Grant was quick to capitalize on it.

Though he built a reputation as a superior tactician, Grant’s greatest strength was his ability to connect with people — players, fans, and media. When Grant spoke to boosters, he’d get them so fired up you could feel the temperature rise in the room. He alternately praised and scolded the media but didn’t hold grudges. He was the master of motivating players while holding them accountable.

Grant had a last-chance speech that he gave in his office. It could be that a player wasn’t fulfilling his potential on the court or in the classroom. Or maybe a player had gotten in trouble with the law.

“Are you willing to cross the bridge?” the coach would ask. “Don’t tell me you are, if you aren’t. Show me you are — by doing everything to cross that bridge and make something of yourself.”

Losing Made Grant Physically Sick

Grant hated losing. It made him physically sick. He was tough to be around in the airport the morning after a road loss.

Once, after losing at Boise State, he told assistant coach Fred Litzenberger, who had served in the military, that he might think about re-enlisting. Turning to Ron Adams, he said, “The media calls you my Secretary of Defense. What we played last night was matador defense. We didn’t stop anyone.”

Grant smiled while he said it, but the message was sent. That team finished 25-8 and made the NCAA Tournament.

Grant “retired” from Fresno State after the 1985-86 season and a 15-15 record. He left for three reasons: his health, the university had teamed with the city to expand Selland Arena rather than build a campus arena, and he didn’t believe the Bulldogs could compete against Tarkanian’s powerhouse UNLV Runnin’ Rebels.

And Then He Rebuilt Colorado State, Too

After a year sitting out, he returned to Colorado State, his alma mater, and rebuilt that program. The Rams were 81-46 under Grant, making the NIT Final Four in 1988 and going to the NCAA Tournament in 1989 and 1990.

Again citing his health, Grant — 57 years old — retired for good after the 1991 season. His record that year: 15-14.

Grant poured so much energy into basketball and he hated losing so much — for him a .500 record was unthinkable — that he couldn’t keep coaching and survive. At times, his blood pressure soared so high it was a miracle he hadn’t died already.

He made the right choice for his family and himself.

And, in Fresno and Fort Collins, we’re glad to have had him for the time we did.

[activecampaign form=19]

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Is ChatGPT Down Again? Here Is What We Know