Share

Samantha “Sam” Bridgeforth could be the poster child for Sunnyside High School’s restorative practices program.

As a sophomore, her grade-point average was 1.0 — a D. She was often angry, rude to school staffers, quick to start swinging her fists in fights. After numerous suspensions, she was inches away from being expelled.

Although she was initially reluctant, she started working with the school’s restorative practices counselor and teacher. Over time, she came to see how her behavior was holding her back, and how she could overcome her challenges.

Mostly, she learned how to believe in herself.

Today, Bridgeforth is an 18-year-old student at Fresno City College, where she takes classes four days a week and is working toward an associate degree in social work. She’s a huge fan of Sunnyside’s restorative practice program, and she’s not alone in that.

Listen to this article:

Some Programs Better Than Others

Fresno Unified Superintendent Bob Nelson says Sunnyside’s program is a good example of how to balance discipline while repairing harm and restoring relationships. Nelson acknowledges that the district suspends more students than any other urban district in California and has struggled to meet the state’s mandate of reducing suspensions.

“Our implementation of restorative practices was a mess in some spots and, in some other places, it was very good … ,” he says. “In some cases, we just made the restoration the accountability structure, and that’s not sufficient. At the same time, you’re not likely to punish kids into long-term change.

More Friendly, Less Disruptive

Sunnyside staffers report a decrease in disruptions and repeat suspensions for fighting and a friendlier atmosphere among students and staff on the southeast Fresno campus since the restorative practices program debuted five years ago.

The program gives Sunnyside’s employees yet another avenue for working with students to help them grow, develop insights, and become more mature and emotionally stable. School officials say that when kids make mistakes there need to be consequences, but they also should have the chance to learn from those mistakes.

Students are encouraged to drop in whenever they feel the need to talk. On a recent morning, Karina Rodriquez, Gordon Wood, and Giovanni Guzman are working on laptop computers where they keep track of contacts and follow-ups with students, and communicate with other school staffers about students’ welfare and well-being.

Rodriquez, now the school’s head counselor, was Sunnyside’s first restorative practices counselor. Wood, who moved to Fresno from Southern California after his daughter enrolled at Fresno State, was hired five years ago as Sunnyside’s head football coach and the school’s first restorative practices teacher. Guzman joined the team last year as the resource counseling assistant.

Knowing Where to Come for Help

The door opens and a young girl in tears approaches Wood, asking to talk. She sits on a large cushion under a window, tears rolling down her face as they huddle in soft conversation.

S213 is known to Sunnyside students as a haven where it’s safe to express sadness or vent anger without fear of being judged or reprimanded.

But when the restorative practices program began, Rodriquez and Wood worked out of separate offices far apart on the vast campus. Neither knew much about restorative practices. Rodriquez started reading and watching YouTube videos to get a better grasp on restorative practices and how it might be integrated at Sunnyside.

Building a New Program From Scratch

There was trial and error in the first couple of years as Rodriquez and Wood figured out what the program should look like.

Rodriquez said she soon realized that she and Wood needed to work in the same room to cement their teamwork. Room S213 became their hub, a place where they could work with students on developing their “emotional intelligence,” using “I” phrases instead of “you,” and developing empathy toward others.

Rodriquez and Wood began to develop processes to help students repair relationships and move forward. Studies show that when students return from a suspension they may feel embarrassed or isolated, and have a hard time settling back into school. Through restorative practices, students learn how to speak up for themselves, develop empathy for others, and improve their social skills.

Restorative Circle Brings Adversaries Face to Face

One of the key steps that contributes to healing is the restorative circle, where students, teachers, and even vice principals come face to face to sort out issues and — hopefully — move the relationship forward. The circles are voluntary, so sometimes it takes gentle prodding to bring students there.

There also may be cultural barriers to overcome, vice principal Pablo Jimenez says.

“My family came from Mexico,” Jimenez says. “The area of Mexico they came from, you don’t apologize. I don’t think I ever heard my mom apologize to me one time. Right or wrong, she’s going to tell you what you do, and you just follow it. There’s no give and take. But that’s not the best way.”

Reluctant to Enter the Circle

As a sophomore, Sam Bridgeforth wasn’t convinced of the benefits of having a restorative circle with Jimenez, who she considered her nemesis. She was convinced that he was out to get her because he seemed to always single her out.

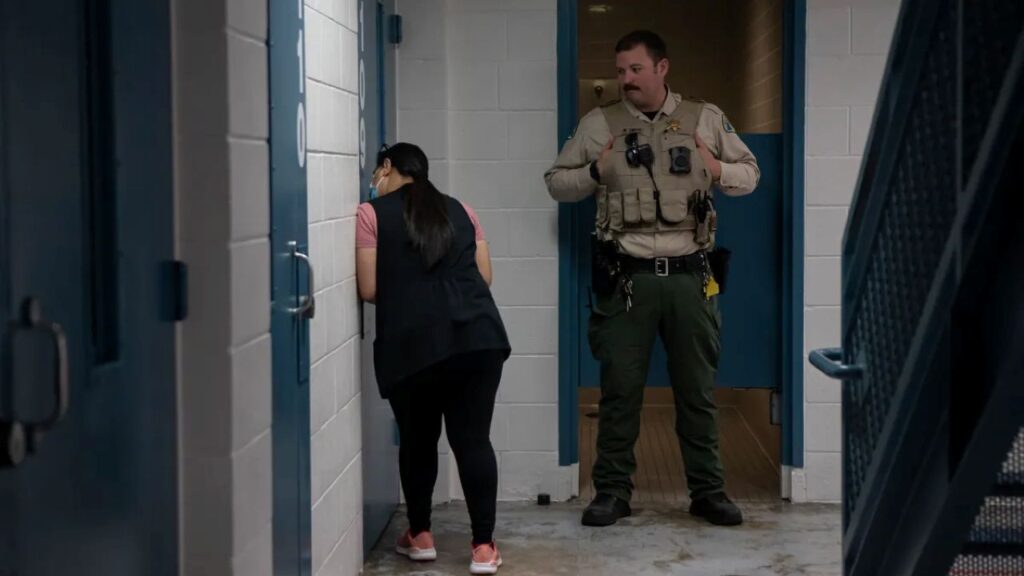

She wasn’t entirely wrong. Jimenez, now in his seventh year at Sunnyside, saw Bridgeforth as a troublemaker who was frequently getting into fights, winding up in his office, and being suspended. He finally was ready to expel her, but she got a reprieve when another vice principal said she was willing to give the teen one more chance.

Meanwhile, yet another fight landed Bridgeforth in court, where she was ordered to attend restorative practices and perform community service.

In their restorative circle, she heard Jimenez say that his goal, and the school’s, was to keep students safe. It was a revelatory experience for the sophomore.

“I know I was getting into a lot of trouble, but I didn’t really know why,” she says. “I didn’t really think that what I was doing was really wrong, until they sat me down and it was like, ‘This is why it’s wrong. You are not safe, and you will not ever be safe, and we’ve got to make sure you’re safe.’ But I thought they were just out to get me and didn’t care if I was safe or not.”

After their restorative circle Bridgeforth was “all positive,” Jimenez recalls. She was a leader among her friends, and some of them also adopted her new, more positive approach to school, and to life.

Changes Gradual on Sunnyside Campus

Jimenez is seeing longer term benefits of restorative practices at the school. He notes that the seats in the waiting area outside his office used to be full of students on a regular basis but are emptier now. And he’s encouraged when he overhears upperclassmen coaching younger students not to run toward fights but to steer clear of them.

History teacher Jon Bath says there have been fewer learning disruptions since the restorative practices program was unveiled at Sunnyside.

Bath, who has taught at the school since 2000, says Sunnyside’s culture has always been student-centric, and the introduction of restorative practices provided a missing link in the school’s support network for students.

In the past if a student was being obnoxious and disruptive, the first option often was sending the student to a vice principal’s office, Bath says. But the vice principals didn’t have time needed to follow up with students, or to intervene in the first place as restorative practices staff do, he says.

Now, students get a chance to hear from another adult who isn’t being judgmental, and then process what they’ve learned. “They know that ‘I can open up and talk, and it’s not about being in trouble,’ ” Bath says.

Students Know How to Self-Refer

Addison Lyons, who teaches sophomore history and AVID and is the head girls track coach, says that he’s no stranger to restorative practices. It’s part of the curriculum at Fresno Pacific University, his alma mater.

He notes that one of the most significant changes since the program began at Sunnyside is that students now don’t hesitate to seek out Wood, Rodriquez, or Guzman when they need someone to talk to, “which has put out a lot of fires that could have been potentially damaging. …”

“Now they know, ‘now, if I ever have a situation like this again, I can go talk to Coach Wood, I can go talk to Ms. Rodriquez or whoever,’ ” he says. “I’ll have kids ask me in class, ‘hey, such-and-such is going on, gotta go talk to Coach.’ So just the fact that they have another way to advocate for themselves before something happens, I think that’s a huge change.”

Two years ago the school added a restorative justice elective class taught by Jared Thompson, who is also the school’s head baseball coach and Men’s Alliance teacher. Some students in the class already have gone through the restorative circle, but others have not.

Reinforcing Social Skills for Later in Life

In a recent two-hour class, students spend the first hour reviewing the results of an emotional intelligence test they had taken the week before and writing an essay about it. In the second hour, the students move their chairs into a huge circle and take turns answering questions posed by Thompson. The circle includes Jaycee Hines, Sunnyside’s new restorative practices counselor. Hines previously worked as an intervention specialist and basketball coach at Washington Union High School.

But soon Thompson is asking questions such as “why is it hard to compromise with someone?” and “What if I said deport all illegals, build a wall. Would you still want to be my friend?”

Outside of class, Thompson says he sees the value in learning how to manage emotions and have empathy, not only for his students but for his own coaching and family relationships.

He references a TED Talks session that explored how students are in school for 12 years learning how to read and write, and do math and science. “But no one teaches you how to manage your emotions, communicate with people, how do you handle your feelings,” Thompson says.

Kids who can learn how to do that will be in a better position to get along with others in the work world as adults, he says.

Expanding the Team

Hines is the latest person to join Sunnyside’s restorative practices team. Guzman, a member of Sunnyside’s Class of 2014, was hired last December as a resource counseling assistant after school officials realized that another staffer was needed to help follow up with students after they go through restorative practices as well as anticipate and head off issues.

“I’ve felt those emotions before,” he says. “Did I handle them in the best way? No, but now that I’m looking back on it and I’ve reflected, I’m able to make better decisions and learn from those mistakes, and that’s kind of what I offer the students. Hey, you’re gonna make mistakes, you’re gonna have downfalls, but there’s always a learning experience in it.”

Misbehavior Still Has Consequences

State education officials have looked to restorative practices to lower the number of students suspended and expelled. Suspensions and expulsions still occur at Sunnyside, but they appear to be declining. In the four school years prior to the introduction of restorative practices, 226 students were suspended and 11 were expelled each year on average, according to state data.

Over the following four years, the average number of students suspended annually dropped to 207, while annual expulsions fell to 5 on average.

Of the 75 originally suspended, only seven were suspended a second time for fighting. And none of them had fought again with the same person as before.

That’s evidence that restorative practices is working at Sunnyside, Rodriquez and Wood say.

Sam Bridgeforth would say that she’s living proof of the program’s success. Her goal now is to graduate from Fresno City by next spring and then earn her bachelor’s degree in social work at Fresno State. When she’s not in school, she’s working part-time at Sunnyside Country Club in the evenings and on weekends.

But before she underwent the restorative practices process, much of her life was negative. She was constantly told that she had no value, no worth. And she believed it.

Hearing a Positive Message, and Believing

Rodriquez was the first person who “kept telling me what I was doing right,” Bridgeforth recalls. “And when she just kept telling me all these things that I was doing right, I was just like, ‘I’m doing that? Are you sure? Like, I don’t see that.’ I was just questioning myself.”

But Rodriquez kept encouraging her. Bridgeforth recalls how the counselor would say, “You’re doing great. You know, you’re growing, you’re learning, you’re gonna make mistakes.”

In her junior year she started going to school rallies and joined the softball team. Benefactors paid for her gear. She started earning As and Bs instead of Ds and Fs.

“She (Rodriquez) was like, you deserve it,” Bridgeforth recalls. “And it really gave me the confidence, that I know that even in the worst classes, that I can still do it. … I knew I could do it. I didn’t have the insecurities I had before, and I just had hope.”

Graduating With Her Class

Her proudest moment? It was graduating on time, with fellow members of the Class of 2019, a night she will never forget.

“It was a really spectacular night of my life. I think that’s the best I have ever had.”

And her graduating grade-point average? It was 3.0 — a solid B.

Categories

Mountain Lion Trio Caught on Camera in Shaver Lake