Share

WASHINGTON — When 16-year-old Carlos Hernandez Vasquez fell ill in a holding facility at the U.S.-Mexico border, he was diagnosed with the flu and given medication, then sent back to a cell to recuperate on a concrete bench.

But Carlos didn’t get better. The Guatemalan migrant died May 20 from flu complications — a glaring sign that Border Patrol stations aren’t set up to manage thousands of children.

And if not, Sanders said, more kids may die.

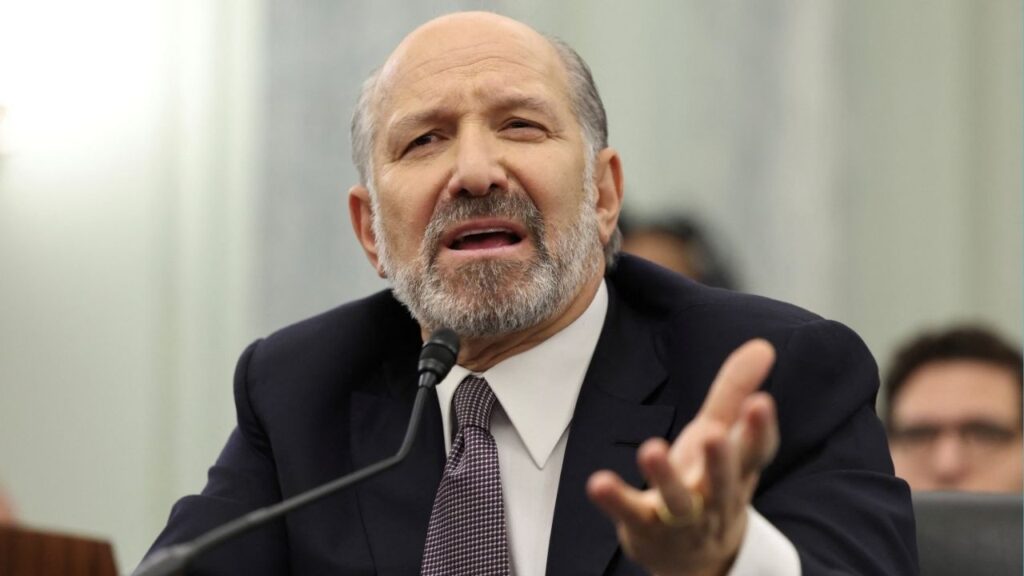

“What occurred, that was something that impacted me profoundly,” Sanders told the AP.

U.S. Border Patrol stations are no place for children. They are bare-bones holding facilities meant for swift processing. But because the entire system is overwhelmed, Border Patrol is routinely holding children for about five days or longer — well beyond the 72-hour mandated window — because the government agency that takes care of minors who cross the border is also overwhelmed. And children must be deemed “fit to travel” before they are transferred.

When Carlos got sick, Border Patrol had about 2,500 kids in its custody, Sanders said. Overall, Border Patrol is holding about 15,000 people. Officials consider 4,000 to be at capacity.

“The death of a child is always a terrible thing, but here is a situation where, because there is not enough funding … they can’t move the people out of our custody,” Sanders said.

Congress Is Nowhere Near Agreement

The Trump administration is struggling to manage a growing number of children and families crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. More than 100,000 people are crossing per month. Immigration facilities are overwhelmed, as are the nonprofits that often take in migrants after they are released from government custody. The numbers have risen dramatically during President Donald Trump’s time in office despite his hard-line immigration policies and border tough-talk.

In addition to Carlos, four other children have died since late last year after being detained by the Border Patrol. Just last week, a 17-year-old girl who had an emergency cesarean section in Mexico was discovered at a border facility in Texas with her premature baby.

Congress is nowhere near agreement on any major immigration law changes. As a stopgap, the Senate Appropriations Committee on Wednesday approved a modified version of the emergency funding request by a 30-1 vote. It’s on its way to a floor vote next week.

The bipartisan vote likely means that the Senate will take the lead in writing the legislation, which needs to pass into law before the House and Senate leave for vacation next week. A spokesman for the House Appropriations Committee chairwoman, Rep. Nita Lowey, D-N.Y., said the panel has drafted its version of the measure and expects a bipartisan vote early next week.

The legislation contains $2.9 billion to care for unaccompanied migrant children — more than 50,000 have been referred to government care since October — and $1.3 billion to care for adults. There’s also money to hire new judges to decide asylum claims.

Getting Emergency Funding Isn’t a Permanent Fix

To win Democratic support, the panel’s chairman, Sen. Richard Shelby, R-Ala., agreed to drop Trump’s request for Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention beds, where adults and a small number of families are held, and agreed to a Democratic provision to block any of the money in the legislation from being diverted to building a border wall.

The spaces offer bathrooms, recreation areas and sleeping quarters that are divided by gender and by families and children traveling alone. Detainees will sleep on mats.

Across the border, Department of Homeland Security volunteers heat up meals for migrants. Government agencies are spending considerably more on perishables, travel and medical checks. A flu epidemic at the facility where Carlos died prompted a temporary shutdown while it was sanitized and cleaned. The supplemental funding will in part pay for those efforts, Sanders said.

Sanders also envisions small infirmaries with beds where people can recuperate if they’re sick, and mobile medical units that can get care faster to rural areas.

Getting the emergency funding isn’t a permanent fix, but it’s is a necessary start, he said.

“We need to be thinking not only about the care for the people in our custody,” Sanders said. “I have a 60,000-person workforce that is strained, are getting sick. The people of CBP need assistance for them.”