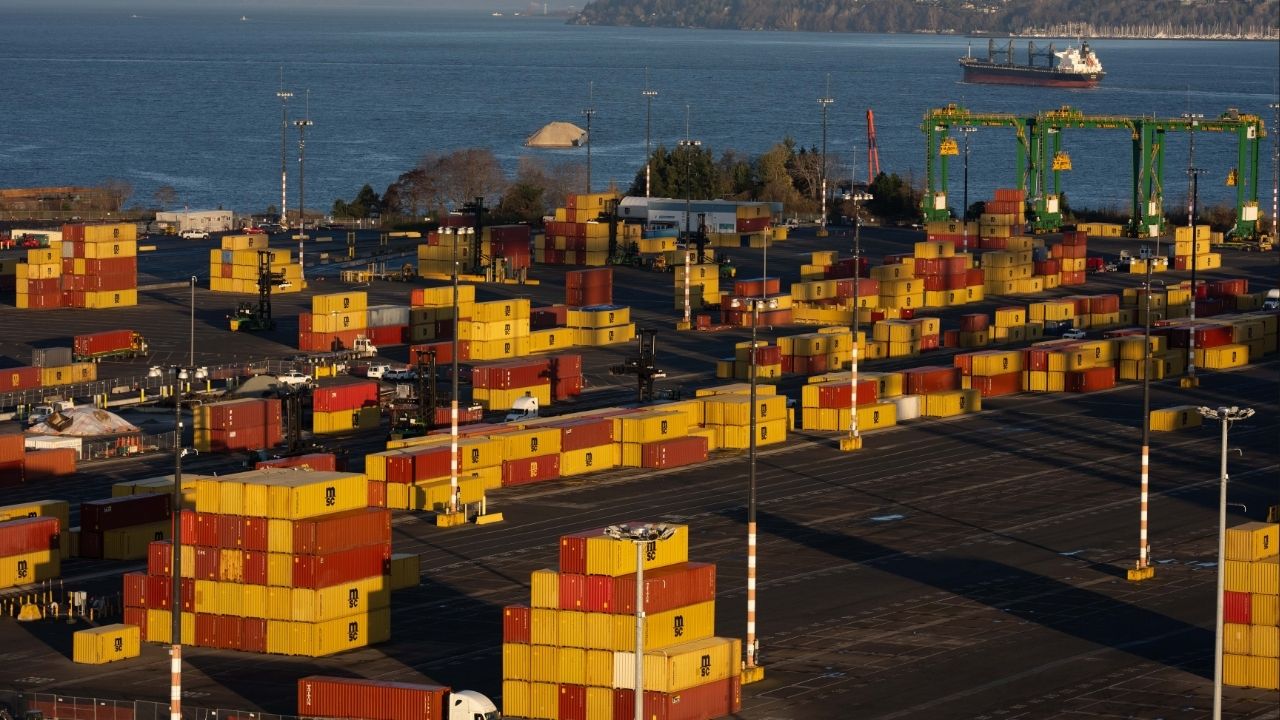

Containers at the Port of Seattle on Dec. 30, 2025. In a major setback for President Donald Trump’s economic agenda, the Supreme Court ruled on Feb. 20, 2026 that he could not invoke the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 to set tariffs on imports. (Ruth Fremson/The New York Times)

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court ruled Friday that President Donald Trump exceeded his authority when he imposed sweeping tariffs on imports from nearly every U.S. trading partner, a major setback for his administration’s second-term agenda.

The court’s 6-3 decision has significant implications for the U.S. economy, consumers and the president’s trade policy. The Trump administration had said that a loss at the Supreme Court could force the government to unwind trade deals with other countries and potentially pay hefty refunds to importers.

Trump is the first president to claim that a 1970s emergency statute, which does not mention the word “tariffs,” allowed him to unilaterally impose the duties without congressional approval.

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts said the statute does not authorize the president to impose tariffs.

“The president asserts the extraordinary power to unilaterally impose tariffs of unlimited amount, duration, and scope. In light of the breadth, history, and constitutional context of that asserted authority, he must identify clear congressional authorization to exercise it,” the chief justice wrote.

Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Brett Kavanaugh dissented.

Early last year, Trump invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 to set tariffs on imported goods from more than 100 countries. He said his goal was to reduce the trade deficit and spur more manufacturing in the United States. Since then, he has used the tariffs to raise revenue and to pressure other countries in trade negotiations.

A dozen states and a group of small businesses, including an educational toy manufacturer and a wine importer, sued over the tariffs, saying the president had unlawfully infringed on Congress’ power under the Constitution to impose taxes. The businesses, which rely on imported goods, argued in court filings that the tariffs had disrupted their operations and led to higher prices for consumers and cutbacks in staffing.

In court filings and social media posts, the president and his advisers cast the outcome of the Supreme Court case as critical to his trade and foreign policies, making clear he would see defeat as a personal rebuke. Without the emergency power, the solicitor general had warned the justices, there would be economic ruin akin to the Great Depression, in addition to an interruption of trade negotiations and diplomatic embarrassment.

But even while battling in court, the president began to explore alternatives to the 1977 law. Trump’s top trade negotiator, Jamieson Greer, said last month that the administration would move quickly to replace any emergency tariffs invalidated by the court with other levies. The president has already used other statutes to set tariffs, including national security-related ones on some specific goods and industries. Still, other laws that more clearly afford the president the power to impose duties are more limited and less flexible than the emergency law.

Trump initially set tariffs on goods imported into the United States from China, Canada and Mexico, saying the levies were a punishment for those nations’ failing to stop the flow of fentanyl. In April, he expanded the duties to imports on goods from nearly all trading partners, saying they were needed to address trade deficits with the rest of the world.

Under the 1970s-era law, the president has the authority to take certain steps in response to a national emergency to “deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat” to “the national security, foreign policy or economy of the United States.” That includes the power to “regulate” the “importation” of foreign property. Past presidents have relied on that language to place sanctions or embargoes on other countries, but not to impose taxes. But the administration has argued that phrase also gives Trump the power to levy tariffs.

The affected businesses countered that the word “regulate” did not encompass the imposition of tariffs. The statute does not include the words “tariffs,” “taxes” or “duties.”

During oral arguments in November, several conservative justices sharply questioned the Trump administration’s lawyer about whether Congress had intentionally delegated to the president broad taxing powers, which the Constitution generally reserves for lawmakers.

The case reached the Supreme Court after three lower courts concluded the tariffs were unlawful.

In August, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled 7-4 that the emergency statute did not authorize the tariffs while declining to decide whether the statute might allow Trump to impose more limited duties.

“Whenever Congress intends to delegate to the president the authority to impose tariffs, it does so explicitly,” the appeals court’s majority said.

—

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Ann E. Marimow/Ruth Fremson

c. 2026 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories