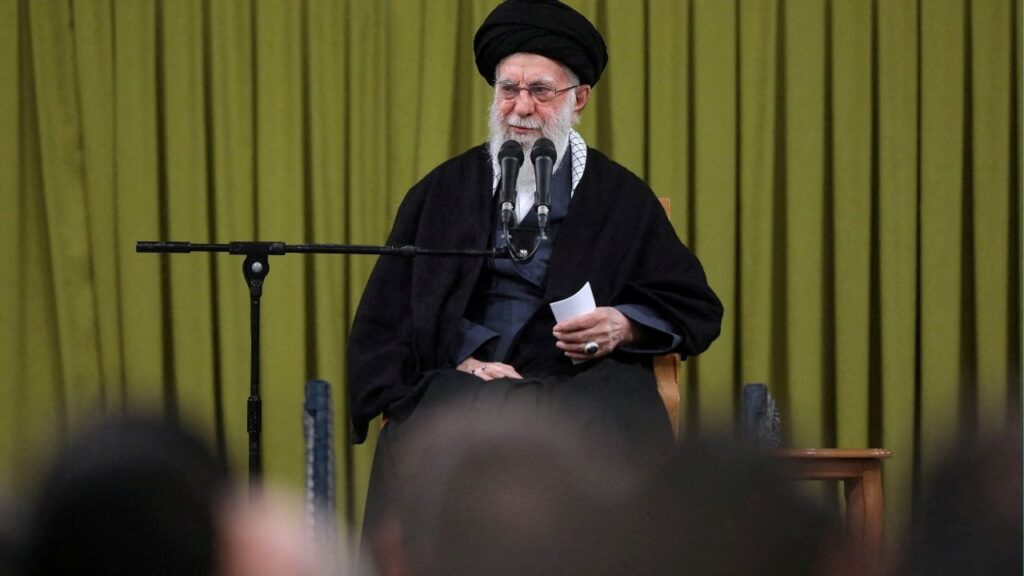

Liu Hu, a journalist from Chongqing, in Sichuan, China, Jan. 27, 2019. Amid a rolling purge of officials and generals accused of corruption, the Chinese authorities have detained two investigative journalists — for writing about corruption. (Giulia Marchi/The New York Times)

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

SHANGHAI — Amid a rolling purge of officials and generals accused of corruption, Chinese authorities have detained two investigative journalists — for writing about corruption.

China’s leader, Xi Jinping, warned after taking power in 2012 that graft would spell “the end of the party and the end of the state” if left unchecked. He has since presided over a yearslong drive to root out what he sees as wayward officials and military officers.

But the targets of that effort, which escalated dramatically last month with the purge of a general second only to Xi in the military command, have all been chosen by the ruling Communist Party, which allows scant space for independent investigations by journalists or others.

In a sign that the party is determined to keep its monopoly on the policing of corrupt officials, a prominent investigative journalist, Liu Hu, and a colleague, Wu Yingjiao, were detained this week after posting an account of official corruption in the southwestern province of Sichuan.

Police in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan, said in a statement that a 50-year-old man surnamed Liu and a 34-year old man surnamed Wu had been detained on suspicion of “making false accusations” and conducting “illegal business operations.”

Liu’s lawyer, Zhou Ze, confirmed the identities of the two detained men on the messaging app WeChat. He wrote that he had visited Liu on Wednesday at a Chengdu detention center, adding that the case against his client appeared to be based solely on the article he coauthored with Wu.

The article, which was published online days before the men were detained, described what they said were the legally dubious, bullying practices of a local official in Pujiang County in Sichuan. The official, they wrote, had a long record of forcibly seizing property from businessmen. The article has since been taken offline by Chinese censors.

The journalists’ detention followed a written warning to Liu from the Chengdu branch of the Discipline Inspection Commission, a party body responsible for investigating corruption, that “reports against public officials should be made through legal channels and in a legal manner.”

Liu responded that “the article we openly published is neither a report nor a complaint, so there’s no need for your reminder.” The New York Times viewed a screenshot of the messages.

China’s investigative reporters once provided rare voices of accountability and criticism in a society tightly controlled by the party, exposing scandals about babies sickened by tainted formula, shoddy buildings toppled by earthquakes and blood-selling schemes backed by the government.

But under Xi, such independent coverage has largely disappeared, with only a handful of journalists left who struggle to push the boundaries. The authorities have harassed and imprisoned dozens of reporters, and news outlets have cut back on in-depth reporting. Censors routinely scrub the internet of downbeat reports about the state of the Chinese economy, while party-controlled media outlets are filled with cheery accounts of life under Xi — and scoffing reports about the misery of life in the West.

Liu once worked for government-backed media in the southern province of Guangdong as an investigative reporter, but he went freelance after being detained in Beijing in 2013. At that time, he was held for nearly a year, accused of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” and of “fabricating and spreading rumors.”

After his release, his work as a freelancer included an investigation into the corruption case of Zhang Jiahui, the vice president of the Hainan High Court, who was later sentenced to 18 years in prison. He also worked on a series about businessmen who were wrongly arrested as leaders of organized crime gangs and whose assets were seized by cash-hungry local governments. In one such case, a serious charge against a Sichuan developer that Liu had written about was withdrawn.

Reporters Without Borders, a group that lobbies for media freedom, denounced the detention of Liu and his colleague, saying in a statement that it “highlights just how restrictive and hostile China has become toward independent reporting.”

It added, “Under Xi Jinping’s leadership, control over news coverage has tightened to near-totalitarian levels, with independent journalists treated as a threat to the state.”

Even a news outlet affiliated with the government of a Chinese province, Shandong, raised questions about the detentions, urging the authorities to handle the case fairly. In a commentary published Tuesday, the outlet wrote that “silence is not conducive to solving problems.”

Asked about the detentions at a news briefing in Beijing, a spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry said, “China is a country ruled by law, and Chinese judicial organs handle cases according to law. Everyone is equal in the face of the law.”

In an interview with the Times several years after his earlier arrest, Liu lamented the rapidly shrinking space for independent journalists. “We’re almost extinct,” he said, “No one is left to reveal the truth.”

—

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Andrew Higgins and Joy Dong/Giulia Marchi

c. 2026 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

OpenAI’s ChatGPT Down for Thousands Again, Downdetector Reports

US Flu Cases Are Rising Again

Snow Drought in the West Reaches Record Levels