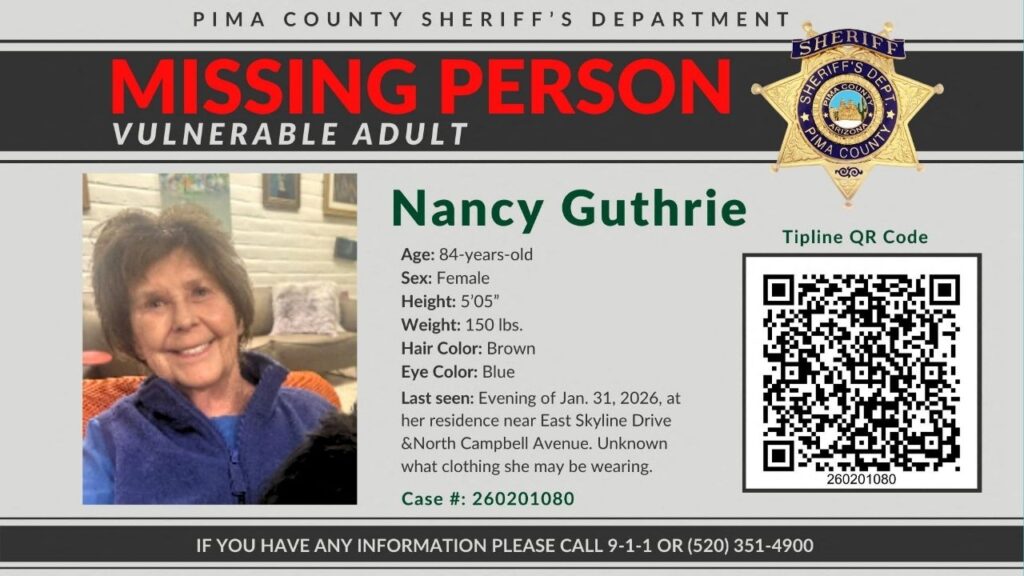

Young soccer fans watch a match between Rhode Island FC and Loudoun United FC at the Centreville Bank Stadium in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Aug. 9, 2025. A wave of small and midsize cities are betting on stadiums anchoring mixed-use development as engines of growth — but those ambitions often fade once the games start. (Cody O'loughlin/The New York Times)

- There have been proposals to build a soccer stadium in downtown Fresno, including one that would have built a $40 million facility in the convention center parking lot.

- A review of new soccer stadiums by The New York Times finds that these ventures "don’t always bring in the revenue and economic activity that are promised."

- Accompanying mixed-use development with housing is often slow to materialize around downtown stadiums.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

(Editor’s Note: There have been several proposals to build a soccer stadium in downtown Fresno, including one in 2021 that would have built a $40 million facility in the Fresno Convention Center parking lot. In making these proposals, stadium proponents tout the benefits to downtown revitalization. However, a review of new soccer stadiums by The New York Times has found that these ventures “don’t always bring in the revenue and economic activity that are promised.” GV Wire is publishing this story to inform the public about the potential pitfalls of investing taxpayer money in these types of projects.)

———

Hordes of fans poured through the entrances and into the merchandise store and concessions markets at the newly built Centreville Bank Stadium in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

It was a sunny Saturday afternoon, and Rhode Island FC was set to play a nationally televised match against Hartford Athletic. The sellout crowd was filled with parents, children and hard-core hometown supporters who sported the club’s blue and yellow jerseys and T-shirts.

The New York Times

With 10,500 seats, the venue, which opened in May, is one of the most expensive lower-tier soccer stadiums in U.S. history.

To build the stadium, Rhode Island officials approved a deal in which the state would pay $132 million over 30 years. But a sticking point was that the project must also include mixed-use development with hundreds of housing units, as well as retail stores, along the adjacent riverfront land.

Rhode Island FC is one of dozens of professional soccer clubs in the United States that have looked to build lavish soccer-specific stadiums — a wave taking hold in small and midsize cities. The projects aim to capitalize on the growing professional soccer market, and provide new revenues for club owners and excellent game-day experiences for fans. Often located downtown or on prime real estate, they are promoted as catalysts for local business and neighborhood revitalization.

But a New York Times review of U.S. professional soccer-specific stadium projects found that the mixed-use development components, particularly ones that include housing, are often delayed or, to date, are incomplete. And those projects, experts say, don’t always bring in the revenue and economic activity that are promised.

Officials could justify using public funding to help build a stadium, because they believe it could benefit the community in the way that a public park might, said Andrew Zimbalist, an economics professor and stadium finance expert at Smith College in Massachusetts.

“But going around and suggesting that these things revivify local downtowns, or attract new investment to the economy, and grow employment and living standards,” he said, “the evidence is that it doesn’t happen.”

High-Stakes Investments

New high-priced soccer cathedrals for clubs in Major League Soccer, the top U.S. men’s professional league, have been built or are underway in large cities such as New York, Los Angeles and Miami. But the bulk of soccer-specific stadiums in the country have been built or planned for lower-tiered clubs in smaller cities.

At least 50 stadiums have been completed or are in the planning or development process for soccer clubs that compete in various tiers of the United Soccer League, the MLS development league, or in the top-tiered National Women’s Soccer League. Among those stadiums, more than two dozen were completed in 2020 or later or are currently being planned or developed.

As the number of stadiums being constructed has gone up, so has the price. For instance, Sacramento Republic FC — which, like Rhode Island FC, plays in the USL Championship — built its privately funded 11,000-seat stadium for just $3 million in 2014.

The club is now in the process of replacing it with a $175 million, 12,000-seat stadium in the city’s Railyards district.

Sports ownership groups view mixed-use development as an important tool to generate revenue that would help them chip away at the high price of buying a franchise, and many have turned to commercial assets recently to diversify their revenue streams, according to a 2024 report from the consulting firm Deloitte.

Such developments have been constructed around the stadiums of NFL franchises such as the Atlanta Falcons and the New England Patriots, and are a central part of the Washington Commanders’ $3.8 billion stadium project.

Stadiums as Anchors to Mixed-Use Development

Owning a stadium and the surrounding mixed-use developments affects a club’s valuation, said Pete Giorgio, who leads Deloitte’s global and U.S. sports practice.

The exact amount, however, is hard to quantify, he continued, since there are so many different factors: the stadium’s size and age; whether the stadium is in the city center or on the periphery of the metro area; whether the venue can host concerts and other nonsporting events; and whether the group owns the stadium, the land it’s on and the entertainment district around it.

“Things get a little bit complicated in terms of how these things are set up,” Giorgio said. But, he added, “every team that is looking at renovating or rebuilding, or building a stadium or arena right now is absolutely looking to see if they can do a mixed-use development around it.”

The Rhode Island ownership group, headed by partners of the real estate development firm Fortuitous Partners, believed building a stadium with state-of-the-art amenities was critical to creating the best possible fan experience, said Dan Kroeber, a club founder.

Rhode Island FC hopes to rise into the top-tiered ranks on par with MLS after the USL launches a first-division league, planned for 2027-28, and an eventual promotion and relegation system in which successful lower-tier clubs can climb the ranks and losing teams fall down the ladder.

“This has always been about bringing sports to phenomenal, what we call, underserved, markets like Rhode Island,” said Brett M. Johnson, co-founder of Rhode Island FC. “But it all comes down to the facility.”

Mixed-Use Development Can Be Slow to Materialize

At least 12 professional soccer-specific stadium projects that have been completed since 2000 have included mixed-use development with housing as part of the proposal. None have been fully realized, but five have been partially completed. Nineteen other projects with housing baked into their mixed-use development have been proposed or are undergoing construction. Many of those projects are in small or midsize cities such as Grand Rapids, Michigan; Des Moines, Iowa; and Rogers, Arkansas.

None of the 600,000 square feet designated for housing, retail, bars, restaurants and commercial space as part of the Colorado Rapids’ $183 million stadium project in Commerce City, Colorado, for instance, has yet been realized. The stadium opened in 2007.

The Rapids’ ownership group is still exploring mixed-use possibilities with city leaders, while evaluating its operations and the land around the stadium, Mike Neary, the group’s executive vice president of business operations and real estate, said in a statement.

There’s always an intention for developers and stadium owners to follow through on the mixed-use development portion of stadium projects, said Erin Talkington, managing director of RCLCO, a real estate consulting firm. But the results are mixed when it comes to whether that development actually materializes — or does so at the scope and time frame that city officials expect, she said.

Most professional sports team ownership groups don’t have much real estate experience, and are often forced to go back to the drawing board on the mixed-use development aspect of the project when it comes time to actually plan it, Talkington said.

The USL president, Paul McDonough, argues that clubs have learned how to turn development around their stadiums into a focal point of their city.

The Colorado Switchbacks, a USL Championship club, have completed the first phase of their plans to build apartments and retail around their 8,000-seat stadium, which opened in 2021 in Colorado Springs, Colorado. The project has quadrupled the revenues of the club, which had struggled financially after debuting in 2015, McDonough said.

“Now they have a great value,” he said. “They are part of the community.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Danielle McLean/Cody O’loughlin

c.2025 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

What to Know About the Homeland Security Shutdown