First responders at an apartment building that a Russian missile struck in Kyiv, Ukraine, August. 28, 2025. Russian attacks and Ukrainian civilian deaths rose as President Trump’s peace talks dragged on during his first year back in the White House. (Finbarr O’Reilly/ The New York Times)

- President Donald Trump is relying on informal envoys Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner to conduct high-stakes negotiations with Iran, Russia and Ukraine, sidelining traditional diplomatic channels.

- The unconventional approach blends dealmaking style with threats of military action, particularly toward Iran, while slowing military pressure on Russia.

- Both Moscow and Tehran appear to be using delay tactics, testing whether Trump’s diplomacy backed by force will translate into concrete agreements.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

BERLIN — Over the past year, the Trump administration has engaged in unconventional diplomacy, gunboat diplomacy and, in the most sensitive crises, diplomacy without diplomats.

On Tuesday, the administration tried all three tactics at once. In Geneva, President Donald Trump’s most trusted envoys — his real estate friend Steve Witkoff and his son-in-law Jared Kushner — engaged the Iranians in the morning, then the Russians and the Ukrainians in the afternoon.

It was a stark example of Trump’s conviction that the State Department and the National Security Council, the two institutions that have coordinated negotiations over global crises for nearly 80 years, are best left on the sidelines. And so the Witkoff-Kushner duo has been at the center of recent efforts to end a nuclear crisis in Iran that has stretched over two decades, and a war in Ukraine that is days away from entering its fifth year.

Dealmakers at the Center

By all accounts, Trump has confidence in their approach, reinforced by their negotiations last year to win a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip and the return of all Israeli hostages held by Hamas. And countries like Russia, Turkey and the Gulf Arab states have welcomed the arrival of the two men, with their transactional approach born of New York property negotiations, especially given the greater flexibility offered by Witkoff and Kushner.

They talk the language of dealmakers and do not spend much time lecturing on human rights or democracy building. And not infrequently, their interlocutors on diplomatic issues are closely linked to the business deals that the Trump and Witkoff families are negotiating.

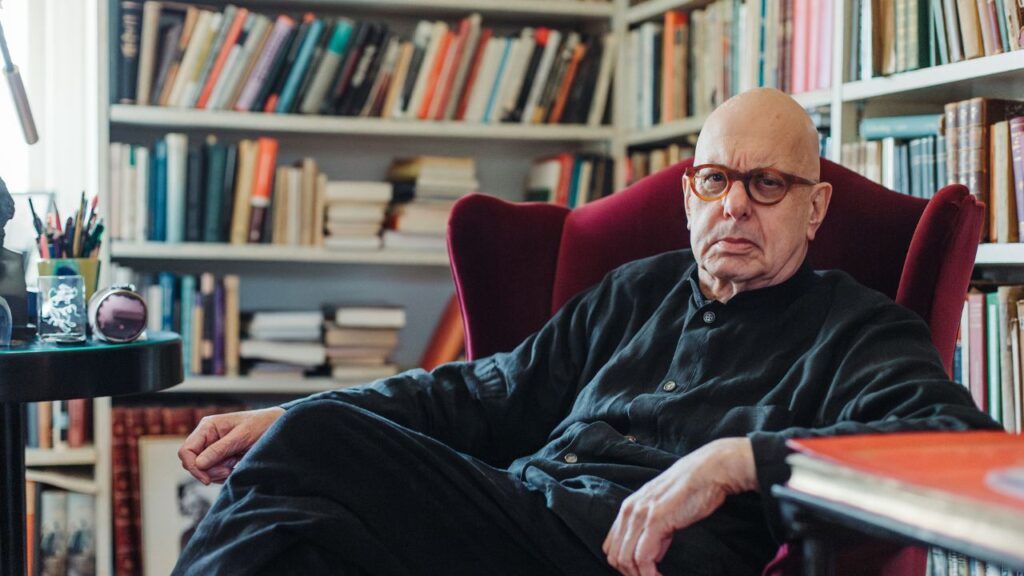

“Some countries really welcome this informal structure at the Trump White House,” said Asli Aydintasbas, a fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington. But, she added, “I have not seen anyone hugely impressed with the diplomatic skills of the current team.”

One person close to the Kremlin said that Russian officials appreciated Witkoff’s warmth and enthusiasm for the negotiations, even as they sometimes doubted his reliability as a messenger. But he was clearly new to the issues dividing Washington and Moscow, and at first brought no other American experts into his negotiations.

More recently, the Russians have been happy to have Kushner’s involvement, the person said, because of his more organized and structured approach.

Some Russians have taken to calling the duo “Witkoff and Zyatkoff,” because “zyat” is Russian for son-in-law. The Iranians also have a nickname for Kushner, using the Persian word for son-in-law: Damad Trump, again defining Kushner’s influence by virtue of his marriage to the president’s daughter, Ivanka Trump.

Iranian media have dedicated coverage and columns to Kushner’s participation. Ahmad Zeidabadi, a prominent political analyst and columnist, wrote in Asr Iran newspaper that Kushner’s participation in talks was something “positive.”

“He represents the pragmatic and softer side of Trump,” he said.

Kushner, in an interview last October, said that his and Witkoff’s approach to diplomacy relied on being “deal guys” who “have to understand people.” Witkoff was known in real estate circles for major transactions, including buying the Woolworth Building, once New York’s tallest skyscraper, in 1998. Kushner followed his father, real estate developer Charles Kushner, into the business and later expanded into private equity.

Jared Kushner holds no official government title and gets no government salary, while Witkoff is a U.S. “special envoy.”

Questions of Experience and Conflicts

In Trump’s first term, Kushner spearheaded the Abraham Accords, which normalized relations between Israel and several Arab countries — though his hopes of bringing Saudi Arabia aboard have not yet come to fruition. Last year, his efforts negotiating the ceasefire in Gaza drew praise even from some Democrats, for pushing closer to ending a war that President Joe Biden could not.

Supporters of the administration see Witkoff and Kushner as ideal negotiators in part because their personal wealth, they say, makes them more resistant to corrupting influences. But both men face questions over apparent conflicts of interest.

Witkoff’s son Zach is the CEO of World Liberty Financial, the Trump family’s cryptocurrency company. An investment firm tied to the United Arab Emirates purchased nearly half the company last year for $500 million.

Kushner raised several billion dollars before Trump’s second term from overseas investors, including government wealth funds in Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE, countries he had worked with when he served as a senior White House adviser during Trump’s first term.

Yet as they engage with Witkoff and Kushner, the Russians and the Iranians share a strategy: delay.

Delay as Strategy

At the Munich Security Conference last weekend, several participants on the edges of the negotiations over Ukraine, which Russia invaded four years ago next Tuesday, said repeatedly that Russia had every reason to engage in the negotiations and little compelling reason to sign an agreement.

President Vladimir Putin believes he is winning, military and intelligence officials from several Western countries said in recent days. And he is convinced that even if it takes 18 months to two years to complete his hold on the Donbas region, each day of fighting and each night of Russian missiles and drones raining down on energy infrastructure and apartment buildings secure him more leverage.

For the Iranians, delay is the regime’s last strategy for survival. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who was in Slovakia and Hungary early this week but is not participating in either of the Geneva negotiations, made the case for pessimism.

“It’s going to be hard,” he told reporters. “It’s been very difficult for anyone to do real deals with Iran, because we’re dealing with radical Shia clerics who are making theological decisions, not geopolitical ones.”

But the commonalities end there. In the Iranian case, Trump is backing up his diplomacy with a threat of fairly imminent military action if there is no progress — maybe in days, perhaps in weeks. In the Russia-Ukraine case, he has slowed down the military pressure, halting the direct provision of arms to Ukraine that took place — with strong congressional support — in the Biden years.

—

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By David E. Sanger and Anton Troianovski/Finbarr O’Reilly

c.2026 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Blackstone Avenue Shelters Crush Fresno Dreams and Businesses