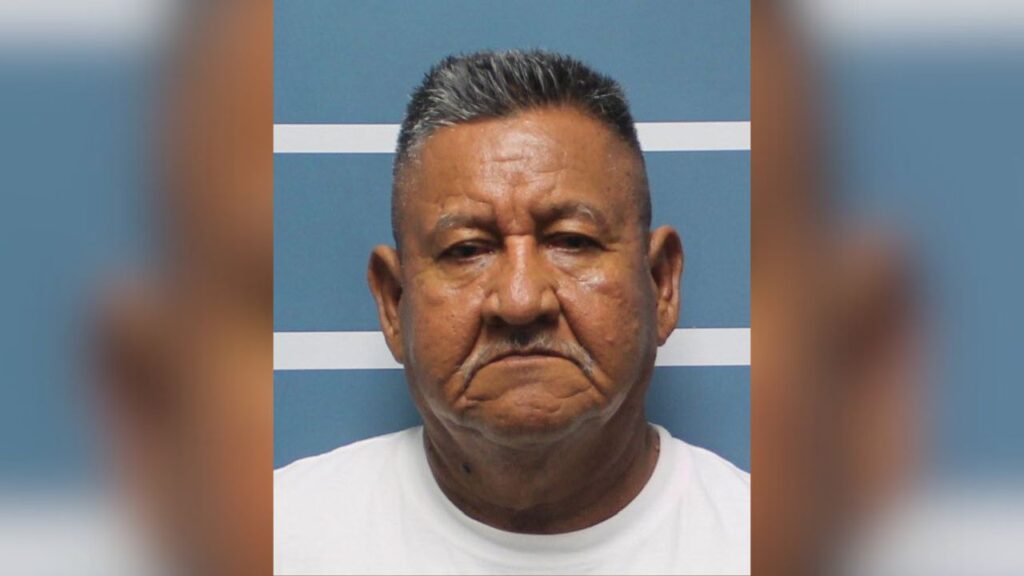

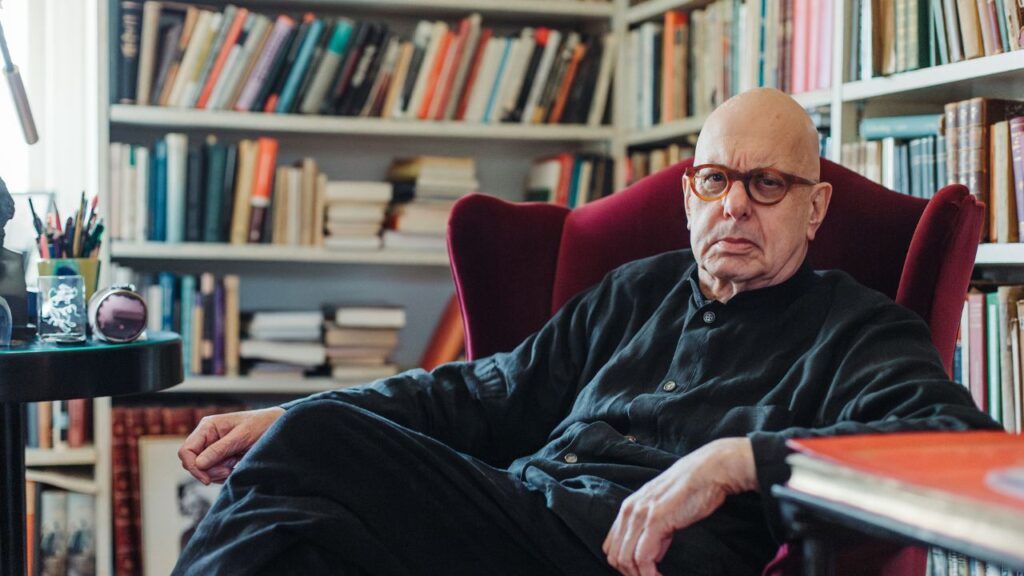

Leon Botstein, who has led Bard College as the president since 1975, at his home on the campus in Annandale-On-Hudson, N.Y., March 19, 2025. Botstein raised millions to save his school from closure— as he sought donations, he talked with Jeffery Epstein about music, watches and young female musicians. (Arden Wray/ The New York Times)

- Leon Botstein, Bard College’s longtime president, maintained contact with Jeffrey Epstein for years after Epstein’s conviction, describing him in emails as a cherished friend.

- Newly released documents show Botstein helped young female musicians connected to Epstein, raising concerns among some students and alumni.

- Despite the revelations, Bard’s trustees and much of the campus leadership have continued to stand by Botstein, who says his interactions were focused on fundraising.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In 1975, Bard College, a quirky liberal arts school awash in debt and with an endowment of about $100,000, faced extinction.

Trustees, seeking an energetic new leader, turned to an odd choice to helm a struggling college: Leon Botstein, a 28-year-old musician and academic. They told him to “build something great or close it.”

Over half a century, Botstein built a kingdom, growing the endowment to $1 billion, expanding into K-12 schools around the country, opening campuses abroad and starting up degrees for prisoners. His persona — charismatic, intellectual, offbeat — became inseparable from the institution itself.

But at some point, Botstein’s efforts to expand his school brought him into contact with another ambitious man, convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

Like many of the celebrities, politicians, finance power brokers and academics who appear in documents recently released by the Department of Justice, Botstein was in touch with Epstein in the years after he was convicted of soliciting prostitution with a minor, sending warm emails and exchanging visits. Botstein’s messages described Epstein as a cherished friend, and newly uncovered emails show how he helped young female musicians in the financier’s orbit.

While newly revealed Epstein connections have led many powerful people to resign from top positions or step out of public life, Botstein has remained in his post so far.

At Bard’s campus, spread across a picturesque 1,200 acres overlooking the Hudson River in New York, Botstein’s friendly solicitations of Epstein have raised eyebrows and upset some students and alumni. But so far, there have been only sporadic calls for Botstein, who recently celebrated his 50th anniversary as leader of the school, to step down.

Botstein has maintained over the years that his meetings with Epstein were entirely for fundraising. Epstein gave a small unsolicited gift to the college in 2011 and dangled the possibility of a major gift that would never come, Botstein said.

Faculty members, divided over how to respond to the new revelations, ultimately decided to do nothing. The student government has not weighed in. Its speaker agreed to an interview for this article before changing her mind without explanation.

A former student organized a protest Tuesday. About 10 people showed up.

And, critically, board members appear to be sticking by Botstein. None have responded to requests for comment; some have previously said that the president is the linchpin of the college’s success.

“For a long time, it was clear to everyone that without Leon there could be no more Bard,” Marcelle Clements, a Bard trustee, told The New Yorker in a 2014 article.

A Routine Courting of a Donor?

Bard College always marched to its own beat, even more so under Botstein. At Bard, applicants can skip the traditional process and instead submit three lengthy essays, and each new student gets a copy of Plato’s “Republic.” The school grew from 600 students in the 1970s to about 2,200 now, with thousands more in affiliated schools.

But the alumni gravitated to music and the arts, not highly paid Wall Street jobs, meaning the college often had to look elsewhere to raise money. Botstein was good at finding it. Some $2.3 billion has been raised in Botstein’s tenure, according to his spokesperson, David Wade.

Some on campus have chalked up their president’s relationship with Epstein as part of the routine of courting wealthy potential donors.

“Fundraising is always relationship building, especially when you’re talking about big gifts,” said Kenneth Stern, the head of a center at Bard and a faculty member. “I don’t think you can go to somebody and say, ‘Give me the money.’”

But Botstein’s critics worry that affection for the longtime leader and fear of a Bard without him have made his supporters blind to behavior that could ultimately hurt the school and its reputation.

“Jeffrey Epstein was a convicted sex offender at the time Bard accepted his gifts and maintained contact with him,” Ambra Hunter, the mother of a student enrolled in one of Bard’s early-college programs, wrote in an email to Botstein over the weekend that she also sent to media.

“Your position as president of a prestigious college helped launder his reputation through association, signaling to students, faculty, donors and the broader public that he remained an acceptable participant in academic life,” she wrote in the email.

A Cherished Friendship or Necessary Evil?

Botstein has said he has been “shocked and appalled at the horrific nature and extent of his monstrous and criminal depravity” of Epstein. He has apologized for involving himself and his college, and called Epstein a “truly evil man.”

Messages that have been publicized already and some newly revealed communications show that they stayed in touch for years — discussing music and their shared interest in watches. Botstein wrote that he cherished his “new friendship” with Epstein and signed off one 2013 message with “Miss you.”

In several emails, they discussed a young woman Epstein wanted Botstein to help.

In 2013, Epstein discussed the woman, a violinist from Europe, with one of his associates, agreeing to pay for her studies in the United States. When her family balked because of his criminal history, he suggested they get a reference from the American Symphony Orchestra, where Botstein was the principal conductor.

Later, Epstein referred to her as “my tall blonde violinist” in one email to Botstein. In another, he told the young woman Botstein would be her “dinner partner” at a gathering. Wade has said that Botstein was unable to attend that dinner because it conflicted with his family’s Rosh Hashana celebration but that he had agreed to drop by beforehand to say hello.

Separately, in a 2014 email, Botstein wrote to Epstein about meeting “your protege pianist.”

In 2012, Botstein’s office had planned a fundraising trip, with one leg including a visit to Epstein’s island. The day after the trip, Botstein thanked Epstein, writing, “That place is great.” But Wade cast doubt on whether Botstein actually visited the island, saying he was referring to “the overall environment of St. Thomas.”

In the years ahead, Botstein would visit Epstein’s town house numerous times, while Epstein would fly his helicopter along the Hudson River and land on Bard’s campus, with young women in tow at least once.

Last week, Botstein wrote to the Bard community to apologize and explain his relationship with Epstein. He wrote that his communication with Epstein became “more sporadic” after it became clear that Epstein would not make a major donation to the college.

“I was not following the revelatory closing chapter of Mr. Epstein’s life and the extent of his crimes until he was arrested in 2019,” Botstein wrote, explaining that he uses a warm tone with prospective donors.

Some say the relationship with Epstein casts a shadow on Botstein’s storied career.

“Do you usually continue pursuing, with that level of regularity, donors who don’t seem to be donating?” Tallulah Woitach, the former student who organized the protest, asked in an interview, adding, “His emails don’t start with, ‘Dear Mr. Epstein’ and sign off, ‘Best.’ They read like text messages.”

But the Justice Department messages serve as something of a Rorschach test, with others taking away a different message.

“When I read the publicized emails between Leon and Epstein,” said Francine Prose, a writer in residence at Bard, “my main thought is, ‘My god, how hard Leon has had to work to keep the lights on all these years.’”

—

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Vimal Patel/Arden Wray

c.2026 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

Blackstone Avenue Shelters Crush Fresno Dreams and Businesses