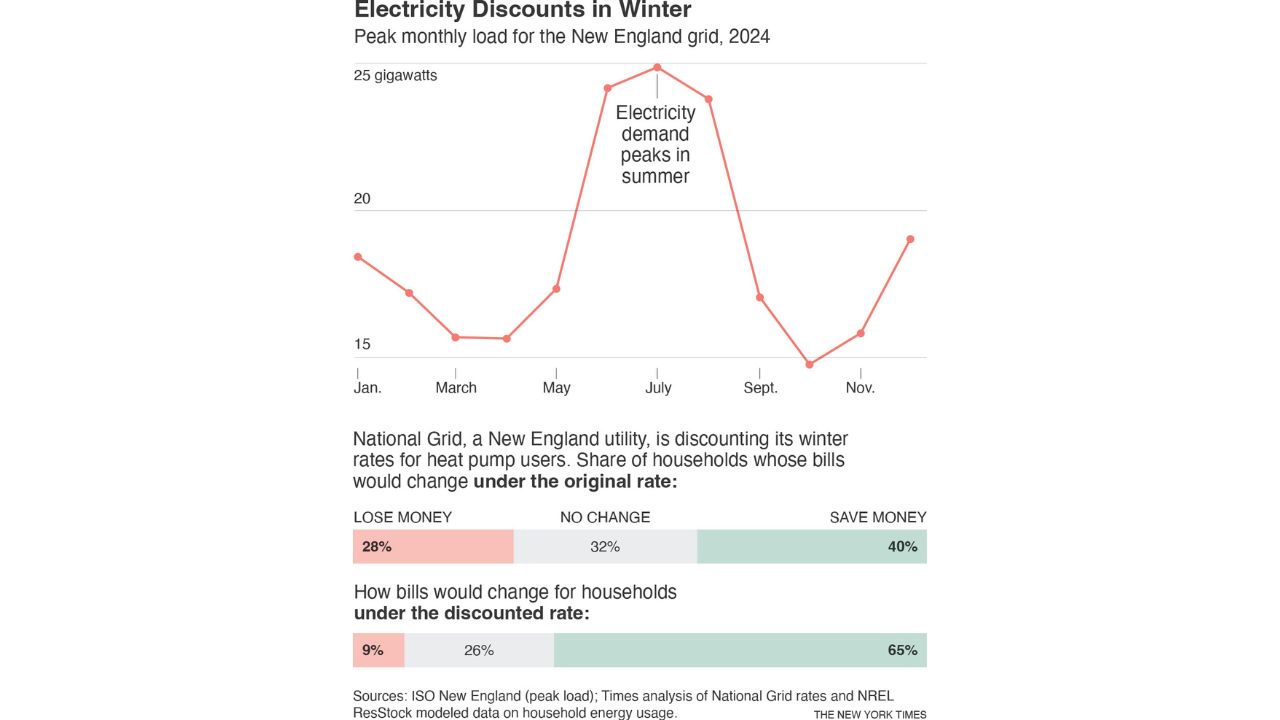

New discounts can make heat pumps go from a bad investment to a good idea. Charts show monthly load on electric grid in New England, plus share of households who would see changed bills under a new National Grid policy at 3.75 x 4.7.

- Some states are offering discounted winter electricity rates to make heat pumps more affordable and reduce emissions.

- Because most power grids are built to handle summer air-conditioning peaks, winter electricity demand often leaves unused capacity.

- The new pricing policies aim to lower costs for heat pump users, though the advantage may fade as winter demand grows in the coming decades.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

For many Americans, installing a heat pump to heat and cool a home can lower household bills in addition to reducing emissions. But in some places, that financial advantage has a big weak spot: winter. High electricity costs and cold temperatures can make heating through the cold season with a heat pump more expensive than using a gas furnace.

Why Winter Is the Weak Spot

Now some states are trying to change that, by lowering winter rates specifically for people with heat pumps. And they’re doing it by taking advantage of the fact that most of the U.S. grid is built for the summer.

Essentially, utilities decide how much customers will have to pay for electricity based on how much peak demand the grid will have to handle. And often peak demand occurs on a hot afternoon in summer, when households all blast their air-conditioning at once.

Because most people use oil or gas, not electricity, to heat their homes, a lot of the capacity in the electric grid goes unused in winter.

People with heat pumps are taking advantage of slack in the system. In winter, they’re buying more electrons without forcing the utility to spend extra dollars on grid upgrades. But they’re paying effectively the same price in winter — when there’s plenty of wiggle room — as they are in summer, when every extra unit of electricity adds stress to the grid.

Basically, say advocates for electrification, as well as states and some utilities, they’re overpaying.

Taking Advantage of Grid Slack

In response, this winter Massachusetts and Minnesota are requiring most of the major utilities in those states to offer discounted rates to people heating with electricity; Colorado is on the way to doing the same. These are states where lawmakers, mostly Democrats, have set targets to reduce planet-warming emissions, and the new rates are supposed to help them do that — especially at a time when rising electricity rates are in conflict with the goal of moving away from fossil fuels. But they’re also an attempt to fairly distribute the costs of keeping up the grid.

State Discounts Change the Math

The discounts range from roughly 4 to 7 cents per kilowatt-hour and apply to all electricity used in the winter. (The typical household uses just shy of 1,000 kilowatt-hours per month, though heating uses more. So a 7 cent discount could amount to hundreds of dollars over the winter.) Other utilities, including smaller and municipal utilities, also offer various electric heating discounts.

A discount can make a heat pump go from a bad investment to a good idea.

Under the existing gas and electric rates set by National Grid, one of Massachusetts’ largest utilities, only around 40% of all households would save money by switching to a heat pump. Some people could lose hundreds of dollars each month, because their electric bill would go up more than their gas bill would fall.

But with National Grid’s new discounted rate, which applies from November through April, the share who would save would shoot up to nearly two-thirds.

In Beverly, Massachusetts, under normal rates, a typical household that swaps out a gas furnace for a heat pump could see its bills go up by some $50 per month in the winter, according to a New York Times analysis of federal data.

But under the new rates, the total winter bill for that house would be significantly lower than with a furnace. And a smaller propane-heated house in western Massachusetts that might have saved a few hundred dollars per winter by switching could save twice that under the new rates.

A heat pump costs significantly more to install than a new furnace or boiler; whether those savings are enough to offset the difference isn’t clear. But policymakers hope that these lower rates will make a heat pump more appealing.

Electric customers are mostly paying utilities to do two things: generate electricity (with, say, a gas power plant or solar array) and deliver it (with physical infrastructure such as poles, wires and substations).

Utilities set delivery rates assuming their customers use electricity in similar ways. But electric heat customers aren’t like other customers: A household that installs a heat pump uses four to five times as much electricity in January as one that doesn’t, according to estimates from National Grid. That means these customers have a very different impact on the grid compared with those who heat with gas.

There are still costs and challenges associated with winter electricity use, and some warmer states already have higher winter peaks. But as long as winter peak demand stays below the summer peak, these electric heating customers are increasing how much electricity the utility can sell, without increasing the cost of keeping up the grid the way that adding to summer usage would.

Because the discounts are based on summer peaks, this solution is probably only a temporary one. If more people use heat pumps — and switch to electric appliances and cars — winter electricity usage will rise. At some point, adding a heat pump will create new strain on the grid: The organization that oversees New England’s grid predicts it’ll start hitting peak demand in the winter, instead of summer, in the mid-2030s. The Midwest grid could do the same.

A Temporary Fix?

That means this rationale for lower delivery costs in winter could vanish. But that’s not necessarily a bad sign for heat pump customers. States that want to encourage electrification will probably look to new ways of charging people for electricity. California, for example, is trying to get people to buy electric cars and household devices by lowering per-kilowatt hour rates for all customers, and raising monthly fixed charges. (That lowers costs overall for households that use a lot of electricity.)

In Massachusetts, utilities will revisit their rates in 2029, at which point the discounts could be renewed, or the state may move toward new ways of paying for the grid. A working group has discussed higher fixed charges as well as time-of-use rates. The goals? Keep electricity affordable, keep the grid running — and encourage people to electrify their homes.

—

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Francesca Paris

c.2026 The New York Times Company