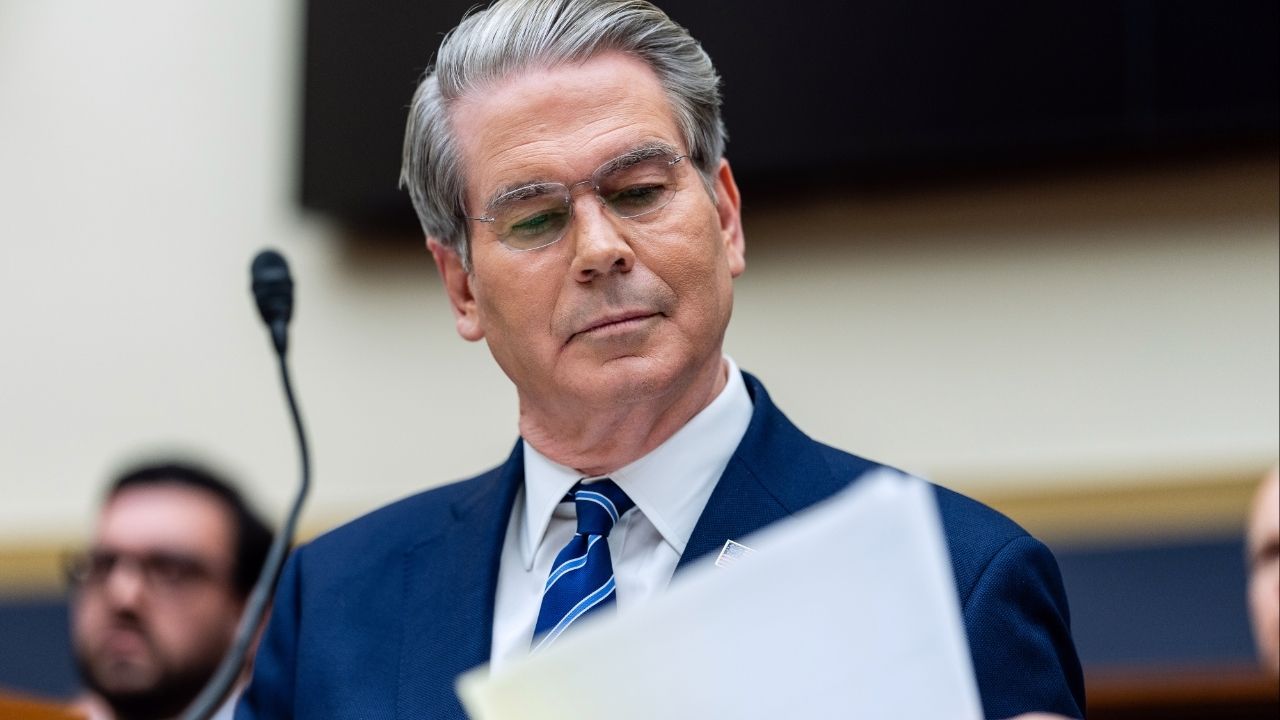

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent appears before the House Financial Services Committee in Washington on Wednesday, Feb. 4, 2026. Bessent, asked about the fall in the price of Bitcoin this week, said the government could not try to stop the decline by ordering banks to buy Bitcoin. (Eric Lee/The New York Times)

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A washout in the stocks of software companies has been flowing through Wall Street this week, as investors realized that the threat of artificial intelligence displacing businesses had arrived.

While the prospect of AI disruptions has hung over the economy for years, a new set of tools released this week by a San Francisco startup forced a sudden reckoning on Wall Street.

Software companies most at risk from the new tools were the hardest hit, as well as the investment funds that lend to these companies. But the sell-off helped push down the broader market. By Thursday, the S&P 500 turned negative for the year after falling on six of the past seven days.

AI has been like rocket fuel for stocks, driving prices to record highs in recent years. But since October that exuberance has been fading, as some realities of this transformative technology have begun to sink in.

Not only are investors growing worried that AI could render certain businesses obsolete, they are also questioning the growing piles of money that companies are spending on AI. On Thursday, investors were spooked by Amazon’s revelation that it planned to spend $200 billion on AI and other large investments this year, exceeding analysts’ predictions by $50 billion; shares fell more than 11% in after-hours trading.

This week, Google’s parent, Alphabet, said it would spend as much as $185 billion this year, and last week Meta said its capital expenses, in large part to support AI, could reach $135 billion.

In the software sector, the catalyst for this week’s sell-off was the release Tuesday by Anthropic, the San Francisco-based artificial intelligence firm, of free plug-in software tools that allow companies to automate functions like customer support and legal services.

Because they were created as “open source” software, any company can download the tools without paying for them. These plug-ins could replace the tools that companies currently sell to businesses.

Another area vulnerable to AI are providers of “software-as-a-service,” or SaaS, a mode of delivering subscription-based computer programs over the internet instead of buying and installing them locally on one’s computer. New, free software models from AI companies have the potential to replace not only the SaaS business model but also much of the workforce behind it.

“There have been a number of these big sell-offs of these SaaS stocks over the past few years as these software models have rolled out,” Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, said in an interview with “TBPN,” a tech-focused streaming show, on Thursday afternoon. “I expect there will be more.”

Analysts have taken to calling the broad sell-off the “SaaSpocalypse.”

Legal Services Drop

Shares of companies like LegalZoom, LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters, which offer legal services and research, dropped as much as 20% over the past week.

Shares of Salesforce, which produces SaaS software for sales workers, have fallen 25% over the past month.

Even companies catering to the arts have been hit. Shares in Adobe and Figma, which produce tools for artists, fell 7% and 20% over the past week, driven by fears that many of the bread-and-butter design tools they provide to creative workers could eventually be automated.

The fervor for AI is not just affecting the software industry. The surge in AI spending has generated enormous demand for random-access memory, or RAM, a kind of chip required to produce the AI hardware built by these companies.

On Wednesday, Qualcomm, which makes microprocessors for smartphones and computers that require RAM, said it faced uncertainty around how much demand it would have for its chips over the next two years. That is, in part, because the skyrocketing cost of memory could dampen consumer demand for new devices. Shares of Qualcomm are down more than 21% this year.

Software companies have also been a favorite target of private-credit lenders, because the companies’ subscription-based business model provides a stable stream of income to support taking on more debt.

Private credit deals, as the name suggests, are not public, but the loans held by related business development companies, or BDCs, are seen as a proxy for the industry.

Roughly half of the software debt held by BDCs, equal to about $45 billion, comes due in 2030 or later, according to analysts at Barclays, raising worries about the length of time until these loans are repaid. The more time a borrower has to repay a loan, the more time there is for the borrower to default — or, in this case, the more time for a business to be displaced by AI.

An exchange-traded fund run by VanEck that contains holdings in many of the major BDCs is down roughly 6% this year and more than 20% over the past 12 months.

Even as Ares Management and Blue Owl Capital — two of the largest private-credit firms — reported results this week that Wall Street analysts largely applauded, the two companies couldn’t escape investors’ worries about AI disruption. Shares of Ares fell more than 10% Thursday, while Blue Owl’s fell 4%.

Bitcoin Tumbles

Bitcoin, a retail-dominated market that tends to swing with some of the popular stock trades, also fell this week, sliding to around $63,000, its lowest level since October 2024.

On Wednesday, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said during a congressional hearing that the government had no power to order banks to buy bitcoin in order to stem the price decline.

As investors dial down their exposure to the more speculative bets like bitcoin and AI-related stocks, they are shifting toward previously unloved sectors that are seen as better insulated through periods of volatility.

So far this year, energy stocks, consumer staples and the materials sector have all gained over 10% while tech has languished.

“After years of tech-driven market leadership, the balance of power is shifting as investors rotate toward traditional ‘old economy’ sectors,” said Angelo Kourkafas, a strategist at the fund manager Edward Jones.

—

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Mike Isaac, Joe Rennison and Maureen Farrell/Eric Lee

c. 2026 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

The Birth Rate Is Plunging. Why Some Say That’s a Good Thing

Bill Clinton to Lawmakers Investigating Epstein: ‘I Saw Nothing’

Mac the Cat Is Guaranteed to Spice Up Your Life