The New York State Police emblem at the Troop G Headquarters in Latham, N.Y., Jan. 1, 2026. An examination of State Police disciplinary files from 2014 to 2024 revealed a far weaker disciplinary system than those used in other large departments in New York. (Cindy Schultz/The New York Times)

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Sammy Sussman

I’ve spent the past 2 1/2 years requesting and reviewing more than 10,000 misconduct files from New York state’s roughly 500 police agencies.

The work has been as tedious as it probably sounds. But it has also contributed to a new era of transparency around policing. These files, many of which had never been reviewed, reveal the systems through which police departments have addressed negligence and misconduct committed by their own.

My work started in 2023, when I filed a request with the Orange County District Attorney’s Office for its “Brady files,” or records about police officers’ potential credibility issues. I assumed I would receive a few files about a handful of officers with known disciplinary histories.

Instead, the office sent me more than 1,600 pages of files pertaining to misconduct by hundreds of officers in the county and the surrounding area.

The ability to get most of these records is relatively new. Starting in 1976, New York state, by law, kept most police personnel records secret. But when the law was repealed in 2020, many departments began making their records available. Others resisted the change, demanding large payments to do the work of pulling the files, providing lengthy timelines or ignoring requests altogether.

In the immediate aftermath of the law’s repeal, the Democrat and Chronicle in Rochester filed records requests with every police department in the state. The news organization received huge troves of records, but it also received a number of denials from police departments, a few of which it took to court. From the files it obtained, the organization published an investigation, “Driving Force,” that documented the toll of hundreds of car crashes by on-duty police officers around the state.

I ran into similar walls. I filed administrative appeals to challenge almost all the denials, citing a growing body of case law requiring the prompt release of these records. In a few instances, I sued to force agencies to comply. (The New York Times, where I worked as a reporter in the Local Investigations Fellowship, a program that helps local reporters produce investigative work about their communities, continues to represent me in a suit against the Erie County Sheriff’s Office.)

Then I stumbled upon a loophole: Although some police departments were denying or delaying reporters’ requests for records, they were required to share files with their county district attorney’s office.

One police chief in Orange County, for example, said in response to my request that there were “no records” of discipline in his department. But records provided by his county district attorney’s office told a different story: An officer in the department had written a confidential letter to members of the village board about accusations of sexual misconduct against the chief, which he denied.

I filed requests with every county district attorney’s office in the state. Not every office replied, and I would often try again (and again). In counties that did, I used the records from the district attorney to ask for records from local police departments. Many departments released records after they learned that their local district attorney had already provided me with a few. In total, I filed more than 800 requests.

In New York, records requests are governed by the Freedom of Information Law, leading some to refer to these requests as FOIL requests. Anyone can file a request with a government agency under this law for access to existing records.

Unlike other states, New York does not confine records requests to state residents. And though agencies most often receive requests from lawyers or journalists, they are generally barred from considering a requester’s job title or motivation while deciding whether to grant access.

Agencies can withhold information that falls within specific privacy exemptions, such as the disclosure of confidential informants, law enforcement techniques or material that would pose an invasion of privacy. In most instances, a requester can ask an agency to redact certain information while still turning over some portions of the text, but some agencies are pushing back in court. Almost all of the files I received were redacted.

I wrote about the contents of the files for New York Focus, a nonprofit newsroom, before joining the Times’ fellowship. I wrote about officers who evaded criminal charges despite driving drunk, an officer who failed to properly investigate a child sexual abuse case and most recently, how the state police department sometimes handed out lax punishments for officer misconduct.

After every article, readers emailed me asking how they could get records for officers in their communities. My process was mind-numbing at times, and I wouldn’t recommend it to everyone. But filing records requests is something the public has a right to do.

—

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

By Sammy Sussman/Cindy Schultz

c. 2026 The New York Times Company

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories

US ICE Releases Man in Minnesota as Agency Head Faced Contempt

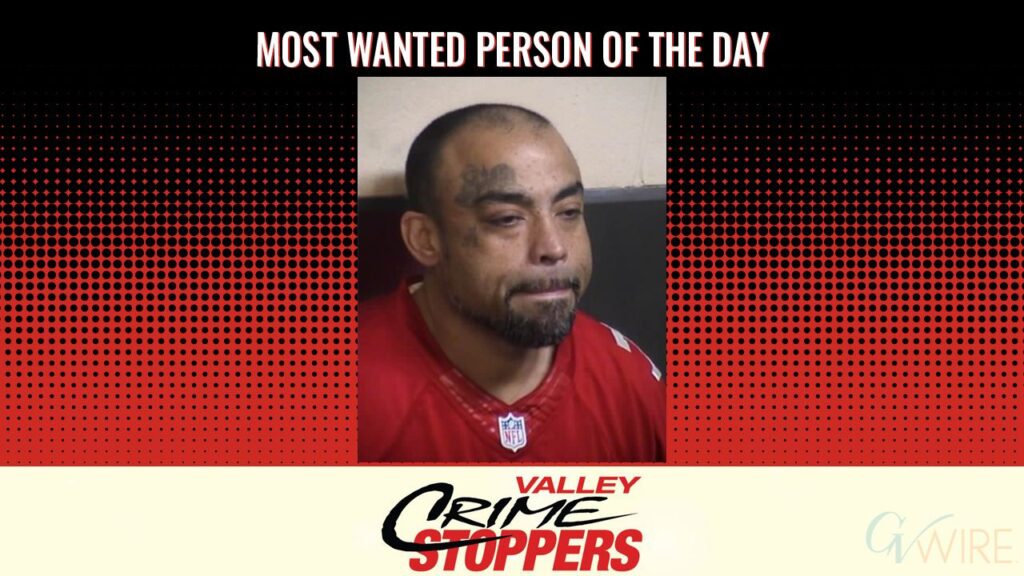

Fresno Police Seek Suspect in River Park Movie Theater Assault

How We Tracked Down Thousands of Police Misconduct Files

Independent Voters Abandon Trump in Droves: Poll