Fresno City Councilmember Brandon Vang expresses gratitude to children from Balderas Elementary, a Hmong Dual Immersion school in his district, for their performance during his first AAPI Celebration at Fresno City Hall. (Office of Brandon Vang)

- For Brandon Vang, his election to the Fresno City Council marks how far the Hmong community has traveled in 50 years, from refugee camps to elected office.

- Vang says that the Hmong story in the Central Valley is now about power, equity, and the fight to be included at every level of society.

- Another shift is happening in daily life, and it is driven mainly by Hmong women.

Share

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Fifty years after Hmong families fled war and rebuilt their lives in the Central Valley, a new chapter is taking shape – one of rising influence.

After a special election in 2025, Brandon Vang emerged as the first Hmong American elected to represent District 5 on the Fresno City Council.

That win made him the second Hmong person elected to the city council in Fresno, California’s fifth-largest city, following Blong Xiong’s trailblazing victory in 2007.

“They understood that representation counts, and that having a voice at City Hall matters,” Vang said.

For Vang, the seat carries history. It marks how far the Hmong community has traveled in 50 years, from refugee camps to elected office.

Vang’s election is also indicative of how Hmong are increasingly rising to prominent leadership roles throughout the Valley. Just under an hour northwest of Fresno, the city of Merced now boasts two Hmong members of its city council – District 6 City Councilman Fue Xiong and Yang Pao Thao, who was recently appointed to represent District 2.

The Hmong story in the Central Valley, Vang said, no longer centers only on survival. It is now about power, equity, and the fight to be included at every level of American society. Young leaders are stepping into politics, education, and business. Elders watch with pride and caution.

“I think the other big piece … is you’re starting to see more Hmong staff, Hmong teachers,” Blong Xiong said. “Our young leaders have more opportunities to be educated.”

But visibility comes with questions about identity.

“The challenge for the next generation is how to maintain part of our Hmong identity, but also be extremely proud of where we are as Hmong Americans,” he said.

For Fresno advocate Lue Yang, greater civic participation, such as the trend being observed in the Valley, is a sign of growth.

“They learn to recognize who is on the city council,” he said. “They recognize who the mayor is. They learn to engage in civic engagement. They can contribute to the community. They can have their voice out loud… for the community to recognize.”

As more Hmong leaders step into public life, they are asking cities to make space for the history that brought the community here.

A Park to Carry Memories Into the Future

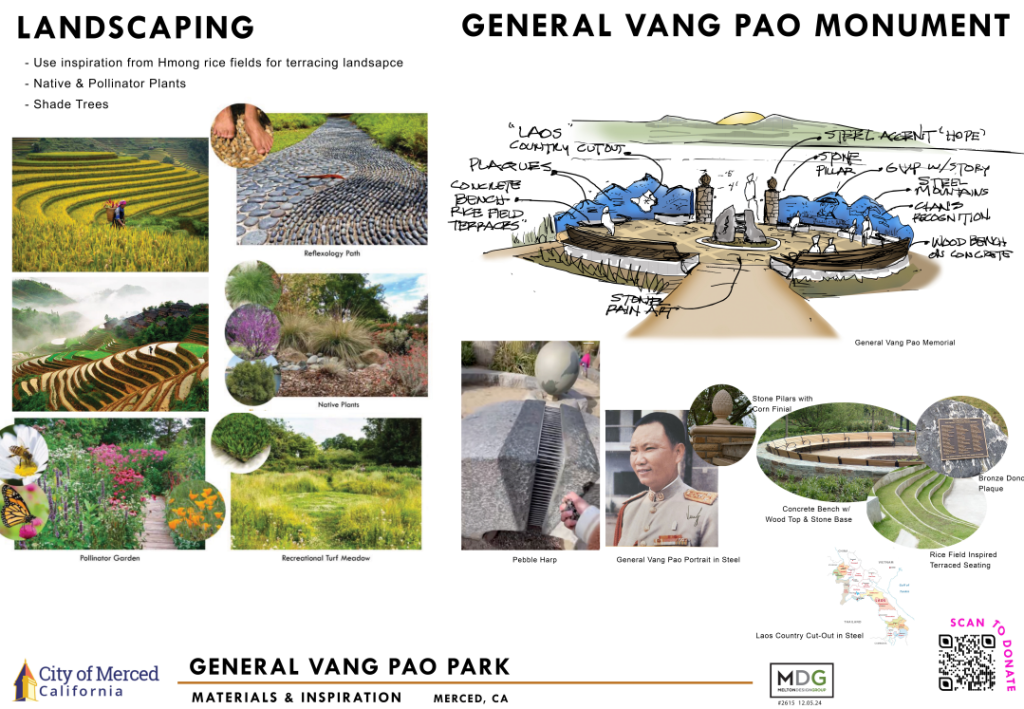

In Merced, on an empty stretch of land in the growing northwest area of the city, plans for General Vang Pao Park are moving forward.

The space is expected to honor the Hmong leader who helped thousands of families reach safety in the U.S.

City officials see the park as both a cultural landmark and a public gathering place, shaped by history, community values, and even ideas about reuse and sustainability.

“These themes … will give our community and visitors a chance to learn about world history, the impact of the Hmong community locally, the importance of inclusion and cohesion,” Merced Parks and Recreation Director Chris Jensen said.

Plans shared in a March presentation to the Merced City Council include a $10 million, 15-acre park that will feature a monument to Pao, sports fields and courts, a playground, walking paths, shaded areas for families, and areas for festivals and cultural gatherings.

Plans include an ADA-accessible playground named for advocate Aletha June, who worked to improve lives in Merced and abroad before she died in 2015.

The project is part of a broader city effort to honor community leaders. Two more parks are planned to be named in memory of Harvard Law School professor Charles Ogletree Jr. and city councilmember Lester Yoshida, though all three sites remain unbuilt due to funding shortages.

The shortages stem from the city’s recent history of collecting minimal developer fees, Jensen said.

City officials did not provide updates on the project’s progress before publication of this series, despite repeated requests from The FOCUS.

But for the community, the park’s meaning has never depended on a timeline.

For Judge Paul Lo, the park’s importance goes beyond amenities. It becomes a touchstone for families.

“We still have a unique identity, a unique culture, a unique language that we can turn to as a source of pride,” he said.

General Pao’s Complicated Legacy

Few names carry more weight in Hmong history than General Vang Pao. He rose to prominence in the 1960s as the leader of the CIA-backed Secret Army in Laos.

His legacy is the subject of debate. According to research by Ryan Dutter at the University of Wisconsin, some scholars and reporters have criticized Pao for alleged abuses during the Secret War, arguing that his leadership came at great cost to his own people.

Others, Dutter notes, reject those claims and defend Pao as a wartime leader navigating impossible circumstances.

For Lo, the general’s story is both central and complicated.

“Vang Pao is definitely a controversial figure,” he acknowledged. “But he played a huge role in the Vietnam War. He was 100% with the Hmong community here.”

Blong Xiong is among the few who worked directly with Pao.

“I found the times that I had to work with the old leadership were very impactful,” he said. “It gave me a much better understanding of what was important to how they see our community.”

For younger generations, the connection to Pao is often secondhand. Many know him through family stories, not personal memory. Still, Xiong hopes the meaning of his leadership endures.

“I hope that they look at the general’s legacy as one that’s like a positive figure,” he said. “He fought hard for his community when we had to be in the streets.”

Xiong points to a simple truth about the diaspora.

“Without his thought and support, and without his leadership, many of us, including our parents, would not be able to be in this country,” he said.

As the community debates legacy and memory, others are pushing for change inside homes and traditions.

Women Leading Change

If political representation is one sign of progress, another shift is happening in daily life. It is driven mainly by Hmong women.

Bouasvanh Lor, executive director of Hmong Culture Camps, spoke about the cultural expectations placed on Hmong women and how those same pressures have also shaped their resilience and accomplishments.

Hmong men, Lor said, sometimes follow old philosophies that view women below them.

“Women don’t hold the same value as they do,” she said. “What we’re missing in our Hmong men is social and emotional skills. Women are the busy bees who are the people behind it, doing all the great work. At the end of the day, we get no credit.”

Behind closed doors, the pressures grow heavier, shaping marriage, safety, and control in the home. Lor talked about older Hmong men taking younger brides and the practice of polygamy in some families.

“Sometimes (the new wife is) underage,” Lor said. “That’s something that needs to stop, and it needs to shift in our culture.”

Once in the U.S., Lor said, some women end up trapped.

“They start beating her or excluding her and keeping her at the house, not teaching her any English, not giving her any job,” she said. “That is something that our generation is still fighting against – for them to stop.”

Growing up, Lor saw the burdens placed on women.

“We’re taught to do all the work, and the men just sit there,” she said. “We have to be on guard all the time, doing 50 things at once. It is expected of us.”

That expectation, she said, is also part of why Hmong women succeed.

“That’s why Hmong women are accelerating in education and other skills,” she said. “The men are falling behind.”

Women, Lor said, are already leading many of the organizations that serve the community.

“It’s mostly women who are doing this work,” she said. “Leadership is there. I want our future Hmong women and men to feel that we all can do it together. You know, we all can be successful together, not be pitted against one another.”

For younger women coming up, doors that once felt closed are starting to open.

“Now they can have mentors and professors that are Hmong women, doctors that are Hmong women, nurses that are Hmong women,” Lor said. “They can have mentors now that we didn’t have before.”

Local advocate See Lee identified the strength she sees in the women around her.

“We do have this deep power within us that’s probably confined and restricted by current systems,” she said. “Every woman knows that you have a powerful presence, regardless of where you are, whether in your silent physical appearance or in the way you talk, but how we understand and utilize that can be so powerful.”

Lor’s vision goes beyond the present. Lor wants a community where families are safer, and men lead with care.

“I would want to see the Hmong young men have more father figures who are compassionate toward their wives,” she said. “I wanna see healthy children and less murder-suicides in our community.”

As gender roles shift, another responsibility rises to the surface.

Learning, Language and the Next Generation

Across every part of the community — politics, gender, culture, memory — one message echoes. The future depends on the youth.

For Vang, preparation is the key.

“We must invest in our youth,” he said. “Many of them will become contributing members of society, while others will be in leadership positions. Having skill sets will make them competitive in the job market.”

Blong Xiong sees representation as the path forward.

“We want to make sure that we have the opportunity to engage in those areas,” Xiong said. “We want people to keep pressure on leaders to be able to understand and participate in the decision-making process that impacts our families, that impacts our communities.”

As the Hmong story moves into its next chapter, Dr. Chai Charles Moau, a public health researcher and longtime cultural advocate in Merced, sees the first generation’s influence alive in the young people stepping forward.

“The Hmong/Mong influence on America, especially younger generations, is in their contributions to the economy through higher education,” he said.

He said the next 50 years will rest on how the community chooses to build on that foundation. His sights are high.

“The Chinese have a saying: ‘The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago, the second-best time is now,’” he said. “By the pace that the Hmong/Mong Americans are going, I wonder what the next 50 years will be like. I hope there (will be) a president in the White House in the next 50 years of a Hmong/Mong descent.”

About the Reporter

As the Bilingual Community Issues Reporter for The Merced FOCUS, Christian De Jesus Betancourt is dedicated to illuminating the vibrant stories of the Latino Community of Merced. His journey is deeply rooted in the experiences of migration and the pursuit of a better life.

RELATED TOPICS:

Categories